|

I have a couple of articles/posts in the works (one with my thoughts on Viking use of embroidery), but they are on hold while I finish processing some wool samples for FFF (an event later this month in AEthelmearc). I have gotten an influx of wool samples for my sheep breeds project and am having a fantastic time preparing with them and learning the history of those breeds.

0 Comments

This is the follow-up to my "Variations in Wool" article. These notes specifically refer to Viking era projects, but many items could pertain to anyone purchasing a whole fleece for use in a historical recreation project. This is not, however, meant to be a checklist of things you must do, or know, before planning a project. Rather, it is a compilation of things that I have learned (and learned to consider) during my own personal journey as an artisan. Because this platform does not allow for effective use of bullets, I have opted to upload it as a document instead of a typical post. One of the joys of my recent wool research is getting to experience first-hand so many amazing varieties of wool. Many of these come from sheep breeds purposely bred for different characteristics such has high fiber yield, staple length, crimp, etc. Through careful research we can determine which breed will supply the best type of fiber for a given project (historical or modern), but we often over look the fact that wool can vary with environmental factors, age, gender and even within the coat of a single sheep. (These notes specifically refer to Viking era or Norse projects, but many of the points could pertain to anyone working with fleece for a historical project.) When considering a whole fleece:

- Lambs born as twins produce less wool as adults than those that are singles. (Khan, 13763)

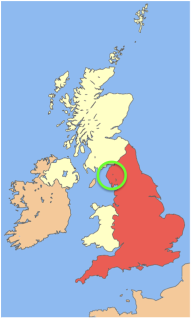

- Steely wool is cause by copper deficiency (loss of crimp, low tensile strength). Copper deficiency can also cause loss of pigment in dark colored sheep. (Khan, 13764) Zinc deficiency causes brittle wool, loss of crimp, and, when extreme, can cause the fleece to shed. Coming soon: Considerations When Choosing Wool for Your Historical Project My other sheep articles: http://awanderingelf.weebly.com/a-wandering-elfs-journey/category/sheep Resources: Dýrmundsson, Ólafur and Niznikowski, Roman. “North European short-tailed breeds of sheep : a review,” 59th Annual Meeting of the European Association for Animal Production. 2008 Ekarius, Carol and Robson, Deborah. The Fleece & Fiber Sourcebook: More Than 200 Fibers, from Animal to Spun Yarn (Storey Publishing, LLC), 2011. Khan, M. Jamshed. “Factors affecting wool quality and quantity in sheep”, African Journal of Biotechnology, Volume 11, 2012. Ostergaard, Else. Woven into the Earth: Textile finds in Norse Greenland (Aarhus University Press), 2004. Ryder, M. L. Sheep & Man (Gerald Duckworth & Co.), 1983. Ryder, M.L. “Survey of European primitive breeds of sheep”, Annales de génétique et de sélection animale, 1981. Initially I was not going to include this breed of sheep in my survey because it is not typically listed being among Northern European Short-Tailed Sheep breeds, due to its having a longer, muscular tail. (Ryder, Sheep & Man, 1983) However, a more recent “Featured Research” article in Science Daily speaks of a new study which proves a strong genetic link between the Herdwick of Britain and flocks in Scandinavia and Iceland (giving credence to the tales that they were brought to England by the Vikings). (Bowles, Carson, Issac.) Ryder has suggested that an examination of Norse wools from Scottish sites show a predominantly hairy fleece type that is different than the native Soay (and also different than the wools found at Roman sites) and believes that this provides a further link between the Herdwick and the sheep brought to the area by the Vikings. Coupling this research and the fact that I have managed to obtain a sample of Herdwick wool, I have opted to include the breed among my other descriptions here.

Their lambs are born solid black, with the face and ears whitening by their first year. After that, the fleece changes to a dark brown and eventually, over years, fades to gray or even white. (Ekarius and Robson, 225) Rams are horned and ewes are naturally polled. Herdwicks have a dual coat, much like that of other primitive breeds (and is described by Ryder as having a Hairy fleece type). The outer coat is comprised of guard hairs, kemp and heterotype hairs. Heterotype hairs, upon close inspection, appear to be a hybrid between the guard hairs and the wool with tips looking like the root end looking like the latter. This special type of fiber actually changes properties during the year to be more warm and insulating in the winter and more like hair to repel water in the summer. (Ekarius and Robson, 267; Piggot and Thirsk, 369; Burns) Additionally, the heterotype hairs are also present in some other members of the North European Short-tailed group of sheep, giving the Herdwick another connection to those breeds. (Ryder, Sheep & Man, 192) The heavy outer coat is coarse, often suited for use in carpet weaving. And the while the undercoat is fine in comparison (and purportedly good for spinning to knit for sweaters), the sample I had had the staple length of both coats was so similar that it was hard to separate the types of fiber. (Unlike dual coated breeds such as the Spaelsau or Icelandic where the hairy coat is quite long compared to the soft under wool, making it easy to grasp the tips and pull the fleece types apart.) Beyond that, even the undercoat, in my samples, was more coarse than I would even care to use for an outergarment, though I can certainly see the appeal of the nice tweedy shades that it would produce. Fiber Info (Are you wondering where I get some of my rare wool samples? I have friends in Norway who have provided some but most of them I get from The Fibre Mine on Etsy! Please check out her shop at some point, the selection is amazing!)

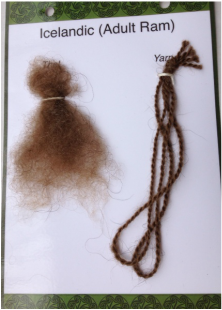

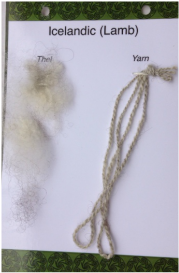

Resources: Burns, Marca. “The development of the fleece and follicle population in Herdwick Sheep.” The Journal of Agricultural Science, Volume 44, Issue 4. Cambridge University Press, 1954. Dianna Bowles, Amanda Carson, Peter Isaac. “Genetic Distinctiveness of the Herdwick Sheep Breed and Two Other Locally Adapted Hill Breeds of the UK.” PLoS ONE, 2014. Dohner, Janet Vorwald. The Encyclopedia of Historic and Endangered Livestock and Poultry Breeds. Yale University Press, 2001. Dýrmundsson, Ólafur and Niznikowski, Roman. “North European short-tailed breeds of sheep : a review,” 59th Annual Meeting of the European Association for Animal Production. 2008 Ekarius, Carol and Robson, Deborah. The Fleece & Fiber Sourcebook: More Than 200 Fibers, from Animal to Spun Yarn. Storey Publishing, LLC, 2011. Herdwick Sheep Breeders Association: http://www.herdwick-sheep.com/ The Herdy Company Blog. http://www.herdy.co.uk Piggot, Stuart and Thirsk, Joan. The Agrarian History of England and Wales: Volume 1, Prehistory to AD 1042. Cambridge University Press, 2011. Ryder, M. L. “Medieval Sheep and Wool Types.” Agricultural Review, Vol. 32, No. 1, 1984. Ryder, M. L. Sheep & Man. Gerald Duckworth & Co., 1983. Ryder, M. L. “Changes in the fleece of sheep following domestication (with a note on the coat of cattle”. Ryder, M. L. "A Survey of European Primitive Breeds of Sheep," Annales de Génétique et de Sélection Animale. 13, no. 4: 381−418, 1981. Ryder, Michael L.. "The History of Sheep Breeds in Britain." The Agricultural History Review, 12, no. 1: 1−12, 65-82. 1964. Visit Cumbria. http://www.visitcumbria.com/herdwick-sheep/ Wrightson, John. Sheep: Breeds and Management. Vinton Publishing, 1898.  Icelandic sheep at MD Sheep & Wool Festival. Icelandic sheep at MD Sheep & Wool Festival. Today's Icelandic sheep are the direct descendants of sheep brought to the island by Viking settlers. It is considered an unimproved breed as there have been no outcrosses allowed to the Icelandic sheep population in its native country. (Ekarius and Robson, 168; Dýrmundsson and Niznikowski, 1276) This fact alone makes this breed very appealing to me for recreation purposes. Further, the wool is also readily available to me (in the U.S.) as there are quite a few breeders here with sizable flocks. Most Icelandic sheep today have horns in both sexes, though on occasion there will be a ewe with no horns or a sheep with four horns. They are classified as a medium sized sheep with ewes weighing 150-160lbs and rams weighing 200-220lbs. (OSU) These animals are double-coated with a variety of possible colors: black, brown, gray, brown-grey, white and patterned colors as well, such as badger-face or mouflon. Many Icelandic flocks today are primarily white, possibly due to selective breeding but I will note that the dominant genetic pattern in Icelandics results in all color being inhibited and, therefore the product is an all white sheep. (Sveinbjarnardottir-dignum, 10) Based on that fact, I have to wonder if possibly more white sheep would not just result naturally over time. Unlike some other sheep from the Northern European Short-tail group, the Icelandic has a distinct difference in the length and fineness of its two coats. The long hairy outer coat is called the tog and the fine wooly undercoat called the thel. It is possible to spin the two together after combing (or directly from the lock) or they can be separated and spun into two vastly different yarns. The tog is coarse, strong and water resistant and is good for making sails or outer garments that need to shed water. The soft, downy thel is much shorter and it spins into a soft, warm yarn that is comfortable to wear next to the skin. Like many primitive sheep, the Icelandic will shed its wool making it possible to roo (pluck) the wool in the summer rather than shear it. The tog and thel shed also shed at different times, allowing one to obtain wool that is largely free from hair. Icelandic wool is also not as greasy compared to many other breeds. I have several whole fleeces and none of them were so unctuous that I could not easily spin in-the-grease if I so chose. The Soay and Shetland that I have handled, however, were so heavy with lanolin that I would not much care for the experience of spinning those unwashed. Sources Cited:

Resources for Icelandic Wool in the U.S.:

Above left: Whole lock of Icelandic ram's wool. Above center: Tog only from an Icelandic ram. Above right: Thel only from an Icelandic ram. Above left: Whole lock of Icelandic lamb's wool. Above center: Tog only from an Icelandic lamb. Above right: Thel only from an Icelandic lamb.

Image from the York Psalter and an Icelandic fleece Image from the York Psalter and an Icelandic fleece Fabric in Viking-era Scandinavia was crafted most often from wool, silk, linen or hemp. During this time, the Norse both imported textiles and produced their own, with some Viking era trade towns, such as Birka, even showing evidence of fabric production on a greater scale than that necessary for single home use. Because the most common fabric found in archeological digs is wool, I wanted to use the most period fiber possible when I began spinning and weaving to better attempt to recreate items from the past. This led me to begin a more in-depth research on which modern sources of wool would be the closest to that which was used in period. The information I have gotten on the subject is far more vast, and decidedly less simple, than I expected when I began this journey. Sheep are one of the oldest domesticated animals, dating back to the Fertile Crescent in 9000 BC (Orsted Brandt, 20). Many researchers believe that the breeds of sheep in Northern Europe have a common ancestor in the Wild Mouflon sheep (which still exists as a feral species in some areas today). Evidence of faunal remains from early settlements shows that sheep and goats have been present in Scandinavia since Neolithic times. (Jennbert, 161) Valued as producers of milk, meat, wool and pelts, the Norse raised sheep and spread them across Northern Europe from the late 8th to the middle of the 11th century. These Viking sheep were the predecessors of the modern Northern European Short-tailed group. (Dýrmundsson and Niznikowski, 1276) Included in this modern classification are the Norwegian Spelsau, Gotland, Finnsheep, Icelandic and many others. To be classed as a Northern European Short-tail, a sheep will, of course, have a short tail (8-10 vertebrae compared to 16-18 in other groups). In addition to that common trait, they also tend to have dual coats, legs with only short hair, a range of colors and patterns, and they tend to be hardy even in harsh climes. Additionally, they can be polled or horned, or with rams only bearing horns. (Dýrmundsson and Niznikowski, 1276) In addition to these features, the most primitive of these breeds have still retained the ability to shed or moult. (Ryder, Survey, 381) Many of these breeds have been “improved” over the centuries, but some, such as the Old Norwegian Sheep, which is thought to be one of the oldest of the breeds, and others, such as the Icelandic sheep, have had less, or in some cases, no additional genetic strains added to improve their bloodlines. (Dýrmundsson and Niznikowski, Table 2) Despite lack of additional bloodlines introduced, these sheep, M. L. Ryder, an authority on the archaeology of sheep and wool at the Wool Research Association in Edinburgh, are “imperfect living fossils” because selective breeding has still often adapted them to what their farmers desired of them. (Ryder, Sheep & Man, 759) Often breeding stock is chosen for better wool, more meat production, parasite resistance, etc., and this changes the breed over time. The small Soay sheep (often classed as a Northern European Shorttail, but sometimes classified as an even older breed, while still being related to the North European sheep) has been determined to be closest to their prehistoric ancestor, the Mouflon. Despite that close genetic connection, these petite sheep have wool that is less hairy than it was in antiquity. (Ryder, Medieval Sheep, 19) One of the most surprising facts I have learned during my study of ancient wool is that during domestication, the the outer coat of kemp (very coarse, brittle hairs) on the earliest sheep evolved into a less course hair, while the under wool actually became more coarse during this evolutionary process. Ryder states that “Few, if any, domestic sheep have wool as fine as that of a wild sheep.” (Ryder, Survey, 385) The process of breeding for better wool and a higher volume of wool actually reduced the quality of the finest fibers the animal generates while allowing for more wool overall to be produced.  Icelandic Sheep by Wellington Grey from London, England Icelandic Sheep by Wellington Grey from London, England Modern Descendants of Viking Sheep There are 34 short-tailed breeds today (descendants of the sheep spread across Europe by the Vikings), including some that are exceptionally rare or even endangered. I am collecting wool samples from those that I can locate and have constructed a series of cards with whole locks and spun samples of each that I display at events. I will be adding photos of each to this blog, along with information about the animals themselves, as I compile my research. Because each of these modern breeds is quite distinct, the wool types can range from soft to coarse, short to long, and from straight to very curly (it can even vary within a breed or on a single sheep). So far, I have learned that despite not being able to find a “perfect” period sheep, I can choose to use wool from these more isolated animals (when available), and that will allow me to make a better attempt at reproducing items for my chosen period. To do this, I often look for fleeces from among the more primitive short-tail breeds. Those animals that have the coats that moult and that tend to be colored rather than white are particularly appealing to me. They are evolutionarily closer to the sheep of the ancient Norse travelers than many of the modern breeds today. (Ryder, Sheep & Man, 765) Because Icelandic wool is easily accessible in the U.S. and because it is one of the breeds least tampered with over time, I often chose to work with it for my projects. I also have a good quantity of Shetland, Spælsau and Gotland on hand for spinning and weaving. Beyond the interesting historic aspects of these fleeces, most wool that I have purchased comes from smaller heritage farms and I enjoy being able to support the farmers' efforts to conserve these historic breeds. Do we, as reenactors, have to use the most period fiber possible? Of course not. We are often limited by finances or availability of certain types of fleece. I think a handspun, handwoven garment can be just as nice when crafted from a purely modern breed and it is not uncommon for a spinner to be gifted large amounts of random wool. Given that I am a huge proponent of UWYH (Use What You Have), I think that the quality of the work can stand on its own regardless of fiber type. I do, however, believe that it is important to make the attempt to understand what wool was like (and the animals that grew it) in historic times and when the situation allows, using the best wool possible.

Further reading: For those interested in seeing a wonderful display of fibers from around the world I cannot recommend The Fleece and Fiber Sourcebook enough. It is filled with fantastic information and photographs and detailed information about the quality of the wool itself. Sheep & Man is a large volume detailing the evolution of sheep throughout the world and is a great history on the evolution and domestication of these animals.

References:

Coming soon: Information and fiber samples of various breeds from the Northern European Short-tailed group. |

About Me

I am mother to a billion cats and am on journey to recreate the past via costume, textiles, culture and food. A Wandering Elf participates in the Amazon Associates program and a small commission is earned on qualifying purchases.

Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

Blogroll of SCA & Costume Bloggers

Below is a collection of some of my favorite places online to look for SCA and historic costuming information.

More Amie Sparrow - 16th Century German Costuming Gianetta Veronese - SCA and Costuming Blog Grazia Morgano - 16th Century A&S Mistress Sahra -Dress From Medieval Turku Hibernaatiopesäke Loose Threads: Cathy's Costume Blog Mistress Mathilde Bourrette - By My Measure: 14th and 15th Century Costuming More than Cod: Exploring Medieval Norway |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed