By the time I finished the skirt, I had decided I was more interested in Central Europe than Northern (despite the time I took to look at some books about the Jastorf Culture) and realized I wanted to take a fresh look at early Celtic material culture. I started to research early Celtic beads (admittedly with no attention being paid to regions, but some attention paid to time period) and I crafted a necklace of glass beads that appealed to me. I make no assertion that this necklace is appropriate for a single specific time and place, but I am very fond of it now and am happy that I made it.

|

Last summer I made an a skirt suitable for someone in Northern, and possibly, Central Europe that could possibly have been worn from 200ish BCE to 200ishCE. There are a lot of ifs and ishes in that because it was purely an experimental item, based on multiple finds, for me to just test the waters to see if I wanted to go that far backwards in time.

By the time I finished the skirt, I had decided I was more interested in Central Europe than Northern (despite the time I took to look at some books about the Jastorf Culture) and realized I wanted to take a fresh look at early Celtic material culture. I started to research early Celtic beads (admittedly with no attention being paid to regions, but some attention paid to time period) and I crafted a necklace of glass beads that appealed to me. I make no assertion that this necklace is appropriate for a single specific time and place, but I am very fond of it now and am happy that I made it.

0 Comments

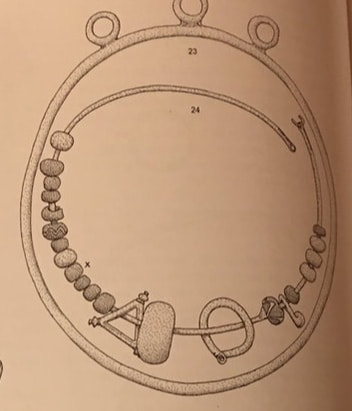

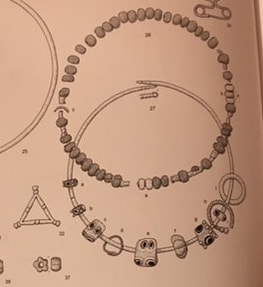

I ordered a mass of books from Germany for my textiles research for early Celtic clothing in February. They have been held up in US Customs since March 23. That means I had to find some other way to occupy my time given that leaving the house/property is not much of an option right now. So in addition to starting a garden, I decided to craft a new-to-me Celtic necklace. While the iconic torque/torc, with its decorated finials, is the the symbol of the Celtic age to many, far simpler neck rings were also in fashion, and where possibly more common in certain times and places. (Note here that the term neckring and torc are also used interchangeably, but I am opting to make a personal distinction here with my terminology to hopefully avoid some confusion.) While reading through the volumes of material that I have collected about the graves from Hallein near the Dürrnberg Saltmines in Austria, I found that an incredible number of the graves contained very simple neckrings in bronze. They seemed to be fashioned out of wire and often had some method of closure on them, whether it was ends that hooked together, or hammered ends that had holes punched in them (some even had traces of chain in one side), or other mechanisms. In addition to the neckrings, several of the graves had very interesting triangular pendants in bronze. They were not all identical but were all roughly an inch across. Some had finials at the corners, others had a decorative “bump” in the center of each leg. In some cases it appears that they were part of a necklace, and in others it is unsure. I have also collected the data from the Durrnberg finds regarding frequency of decorated neck rings, types of closures, and where the triangular pendants have been found, but I need to compile it into a document digestible to those who do not read my rambling shorthand. At some point I hope to upload that information here. For my project, I opted instead of bronze to use silver wire (10g) to form the neckring and I tapered and curled the ends. I used a number of glass beads appropriate to the region and early La Tene period and one bronze triangular pendant.

I have been following the Kern Schoolhouse find in Switzerland for sometime and asked on a SCA group on FB for Celtic (and other early period studies) if anyone knew if the data was yet published or had additional info besides the obvious (the press releases, the City of Zurich page, anything that ran in main stream media), and there was silence.

This is a very different, and less populated, world than that of Viking reenactment. Post a question like that on a Viking group and you would likely a number of people who have either already pulled the article, or who know the exact publication date and have it on order, or whom at least know who the authors of the pending project are (so they can stalk them until publication). Kelticos used to be the go-to place for information, but it seems that forum is less updated than it was back-in-the-day (at least on the types of material culture in which I am most interested). It is also blocked from my lunchtime-research due to being an insecure site. Sigh. The silence on the subject was still was surprising to me. In a way it is a little frustrating (though absolutely no one's fault), but also a little exciting to dive into a less populated pool. But back to Kern: City of Zurich (this has the links for the dig photos as well as the artifacts): www.stadt-zuerich.ch/hbd/de/index/ueber_das_departement/medien/medienmitteilungen/2019/juli/190705a.html The initial media release on the project: www.stadt-zuerich.ch/hbd/de/index/ueber_das_departement/medien/medienmitteilungen/2017/170505a.html The Smithsonian piece is here: www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/iron-age-celtic-woman-was-buried-hollowed-out-tree-trunk-180972773/ LiveScience: www.livescience.com/66056-iron-age-celtic-woman-burial.html There are a number of other news articles on this find, but I am excitedly waiting for the in-depth analysis of the textiles! When I first started out in the SCA, many people were doing “Early Celt”, especially for Pennsic. I was told the most accurate thing to do was to get homespun cotton (a type of quilting cloth) in plaids and make bogdresses for this look. Of course, no one ever addressed the fact that “Early Celt” covers a vast range of time and geography. Over a thousand years and more than a dozen modern countries. Most amusedly so, I was presented with the idea that the ultimate attire for the well-to-do “Early Celt” was not only a plaid, but a patchwork garment (preferably with the pieces made of plaid textiles). One image gets used over and over, even now, to illustrate what many believe to be the quintessential Celtic look. I am only going to briefly address my thoughts on patchwork/piecework clothing in early history. I am also not going to make any sweeping statements that this was “never” done, but it is not something for which I have seen much evidence, especially for a status garment. (We do have items like the Bernuthsfeld tunic, which has been extensively repaired to the point that it is nearly entirely patchwork at this point.). My rationale for “patchwork” garments not being much of a fashion is pretty extensive.

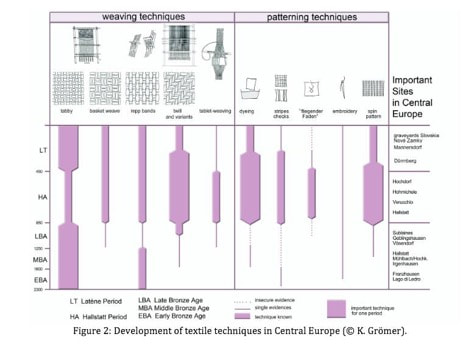

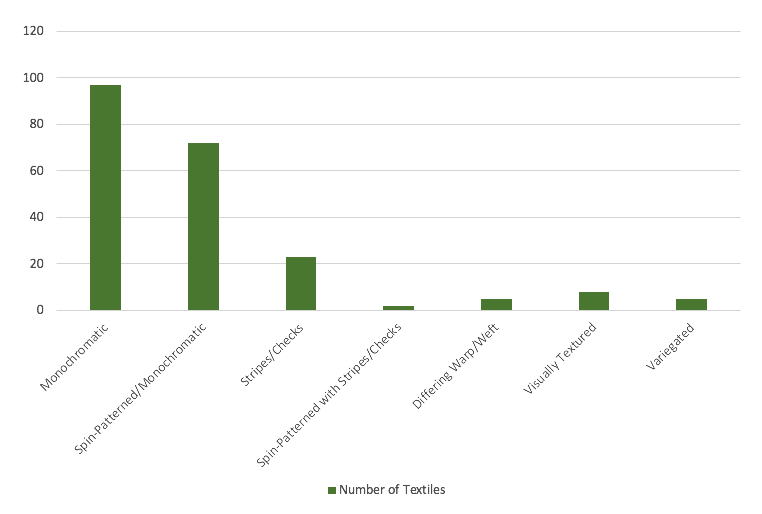

Fortunately, I already have great resources such as Karina Grömer’s work on Central Europe to help paint a better picture of period textiles. In her paper “Textiles Materials and Techniques of Central Europe in the 2nd and 1st Millennia BC” she has the following absolutely fabulous chart.  This item beautifully illustrates the shift in trends from things like a dominance of twills during the Hallstatt period to the later prevalence of tabby textiles by the end of the La Tene period (450-1BCE). This also shows us the relative rarity of embroidery (something that I addressed recently here http://awanderingelf.weebly.com/blog-my-journey/ancient-embroidery-or-the-lack-thereof ), and the thing most pertinent to this discussion, stripes and checks in textiles. The popular image of the early Celt, especially in the SCA, is that of a person who wears plaid tunic, pants, and cloak. Articles even often feature this image of ancient textiles as source for historic Celtic plaids. The compilation is not “wrong” but it certainly lacks context when it is used. According to Grömer’s chart, stripes and checks were a known technique in the Hallstatt period, but not an “important” one (it is not a dominant technique for the time). This holds for the early La Tène period, but tapers off to the “single evidence” category after that. In Grömer’s other works, such as her book The Art of Prehistoric Textile Making, she discusses that during the La Tène period, the favor also shifts from warp stripes as a result of textile production becoming an industry, rather than merely domestic work to fill a family’s needs. All of this results in me asking many questions, the foremost of which is exactly HOW much in the way of stripes or plaids should I be incorporating in a single costume. I am hoping the La Tene textile chart I am working on will answer that once the rest of my books arrive from Germany, but for the time being, I decided to take a more critical look at some of the Hallstatt textiles, because I do already have that material on hand. First let me state that the book Textiles from Hallstatt is nothing short of amazing. I love this volume, and the work that went into it. The book discuses textiles, textile production, costume and then has a catalog (with excellent photos and highly detailed information) on the textiles. Each fragment is categorized in a number of ways, including by weave, presence of dye, if there are seams, if it is spin-patterned or woven as a color pattern and if it is cloth, band, or cord. I am looking at this from a different perspective than the author who is doing the scientific work of categorizing the textile fragments. I am viewing this as a reenactor trying to determine the most appropriate fabrics for a kit, and added an additional two categories. In book’s definition of “Pattern”, textiles with different colored warp and weft threads are included (an example would a cloth with a completely yellow warp and brown weft). This is definitely a way of creating visual interest in a garment, but it is very different than weaving in a color pattern that shows as a stripe or check. Therefore, I created a separate category for those items. The other change I have made is to separate out “speckeled” textiles. Sometimes Grömer lists these as a Pattern, sometimes not. These can be a result of using threads that include both light and dark fibres (giving a tweed like appearance) or it can be by using yarns of different shades, or perhaps a single yarn that is variegated due to several shades of brown being used to spin it. Sometimes when woven, this will also produce a “speckled” textile (though I prefer the term “visually textured”), but sometimes the way the yarns align on the loom, it reads as stripes. Because these always tend to be in the same color family, and are very random, I have listed them separately from more deliberately patterned stripes and plaids if the textile visually looks more patterned rather than just textured (which also often have much more contrast between colors). The idea of speckeled textiles is very interesting to me, especially those resulting in less-than-deliberate striping. When ancient authors did mention patterned cloth were they only referring to brightly contrasted intentional patterning, or did this also apply to the naturally pigmented wool that could vary in shade and can appear striped when woven into a garment? Authors such as Johanna Banck-Burgess mentions some of the issues with ancient sources in her book Instruments of Power: Celtic Textiles, these include things such as linguistic issues within the sources and also the fact that some of the ancient authors never traveled to Gaul or elsewhere. Further, many cultures in Europe at the time wore plaids or stripes, which only further muddies the waters here. The purpose in this exercise is to determine how prevalent the use of deliberate colored stripes and plaids is among the Hallstatt textiles to later compare to the hypothetically lesser use of them during the La Tène period. The book cites that 1/5 of the Hallstatt textiles were patterned. For my survey, I have removed bands and cords from the list of textiles, as well as some of the fragments that were too disintegrated to determine if they were indeed previously cloth or cord. I also am ONLY including items from the Iron Age body of work. If two different textiles are sewn together, I count them separately. Also important to note is the fact the patterned fabrics from this site are only two colors (bands might be three colors). Some of the Durrnberg textiles are three (and I hope to determine what percentage of those are three verses two once the resources arrive). My categories are as follows:

The chart below shows the number of textiles in each category. Further, if you add all of the monochromatic textiles (both plain and spin-patterned) as well as those that only present a tweed-like texture (rather than a monochromatic pattern), we are looking at 83.4% of the textiles being essentially solid-colored. 11.7% are striped/checked. 2.3% have different colored warp and weft and 2.3% have variegated stripes.

The vast majority of the textiles from this site are solid. I look forward to seeing the Durrnberg material as well, to compare to this data (as well as that from other La Tene period sites). I am, however, already starting to believe that while stripes and checks were in use by the early Celtic cultures, that they are not as prevalent as myth would have us believe. The beads in the cover photo are all ones I made last summer for my Ugly Skirt kit. I am VERY pleased with how they turned out and am working on improving my skills in recreating very early glass beads.

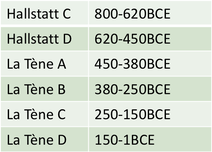

The yellow bead with the double row of blue and white eye beads is one that caught the eye of a friend who centers her focus on Carthage and Punic history. She asked me to make some for her and that started me researching additional beads for her kit. And then I realized that they are the very same beads I need for mine, including fan favorites like derpy rams and big fugly beads like the aqua ones in the photo below that I was playing with last week. At least it will be easy to make sure all of these experiments find homes!  Fortunately, I have a much better sense of how to proceed in researching something than I did when I started my Viking journey. I am currently in the process, as I mentioned before, of re-reading everything I have on Celtic textiles, clothing and culture, and slowly pulling in some new material at the same time. I am doing much better this time at maintaining a bibliography as I go (this will be linked here eventually). I am also building out a list of extant textiles for the time and location at which I am looking. At this moment I am starting with La Tène A and B, so am collecting the data on the entire La Tène period, as well as Hallstatt D. I actually had to print myself a chart and map to keep new my workstation so that I can remind myself of what fits where (as some people label a find simply with a date and others list it by century). Yes, that is still a very broad range of time that I am looking at, but I do so for two reasons. The first is to see how things changed over time and what trends developed. The second is because there is a lot of data that is simply missing, and you really have to fill in the blanks, and I like to have an idea of what direction that will take me.

As I also mentioned earlier, I am specifically looking at Central Europe, with a focus on southern Germany and Western Austria. My initial thoughts were to pull things from those specific locations as well as Switzerland and France, but after doing some reading yesterday I see that some authors lump Germany and Austria in with the material for the Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and Yugoslavia for the La Tène period (which France and Germany are more similar in the prior Hallstatt period), so this is something I now intend to look at further. I think I have added over a dozen new physical books to my library this year, with 4 more on the way. Add to that dozens (hundreds?) of PDFs and I certainly have enough material to keep me happy for awhile. I also have the ILL librarian sourcing several key documents for me that I simply could not find to purchase at all. My first sweep for data includes gathering information on wool types (which I have now done), dye studies (I definitely have enough to go on), and textile catalogs so that I can form one big document where I can sort and view things as needed. I already have a list of questions that I want to try to answer before I start a weaving project this spring. In addition to all of this, I am gathering images and icons of clothed human figures in period so that can start experimenting with garb types. Oh, and also, have you looked at the positively incredible array of jewelry these people possessed? I am looking at my specific time frame and narrowing town the bling that I hope to try to make soon as well. And beads. So many amazing beads (most of which are the same types of beads from Carthage that I am working on for a friend, so I am delighted to not have to print more images to tape to the studio walls). Looking forward to start compiling real thoughts soon! When I first joined the SCA, my interest was all things Irish, or, more broadly, if somewhat inaccurately, all things Celtic. I loved the legends of lore of Dark Ages Ireland, but my modern vanity warred with that interest (and won) in favor of things far later in time (and far more flattering). My household all still did "Early Celt" for events like Pennsic, but looking back, I somewhat cringe at my ideas of what that entailed.

Even while studying Viking Age textiles and dress, I was reading anything I came across about the early Celts, and now it is finally time to start assembling my thoughts on my reading, and put to test some ideas I have had. This separate blog will cover that material, including textiles, beads and my attempts to build kits for the La Téne period in Central Europe. For the moment I am, out of necessity, trying to center my research on the early La Téne period (LT A and LT B for the most part), and regionally I am looking at southern Germany (particularly Baden-Wurrtemberg and Bavaria) and western Austria, though I am tangentially also looking at Switzerland and eastern France. I have materials that reach further out in both time and place, but in an effort to reign in the research and start producing things, I am trying to contain things a bit in terms of time and place. Maybe. Hopefully. To start, I have tracked down a number of catalogs of textiles from these areas and am compiling them into one spread sheet. I am reading everything I can on the topic and looking into not only the beads found in the regions, but in glass working centres there as well. I hope by late spring to have my loom warped up and in the meantime, I will start crafting test-garments from commercial textiles. I do not think I can adequately express how energized and excited I am by this project and process. Viking Age research was difficult. I had to wade through a mass of difficult-to-source materials and work with little in the way of evidence to try to make intelligent reconstructions. Early Early Period (as I call it) is even more difficult. At least with Viking Age work, there were other reenactors who had assembled nice bibliographies from which I could bounce into piles of amazing papers. There is a wealth of information on my new focus area, but not in the same easy-to-get-started format. I am already hitting stumbling blocks in tracking down books I am sure I need (there are a few that have no copies in US libraries at all), and I think my mailman is sick already of delivering heavy packages from Germany to my house. And even once I get all of my sources lined up, there is far less in the way of extant garments to make sense of complete costume. It is absolutely exhilarating. I feel very refreshed (something I much need these days) and hope to make some other major changes in my SCA life going forward as well. |

Iron Age Celtic StudiesMy first interest in historic costume and culture was for all things Celtic. I knew so little about it three decades ago, but have been slowly piecing together things and am starting to build up a persona for the Iron Age in Central Europe. Archives

August 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed