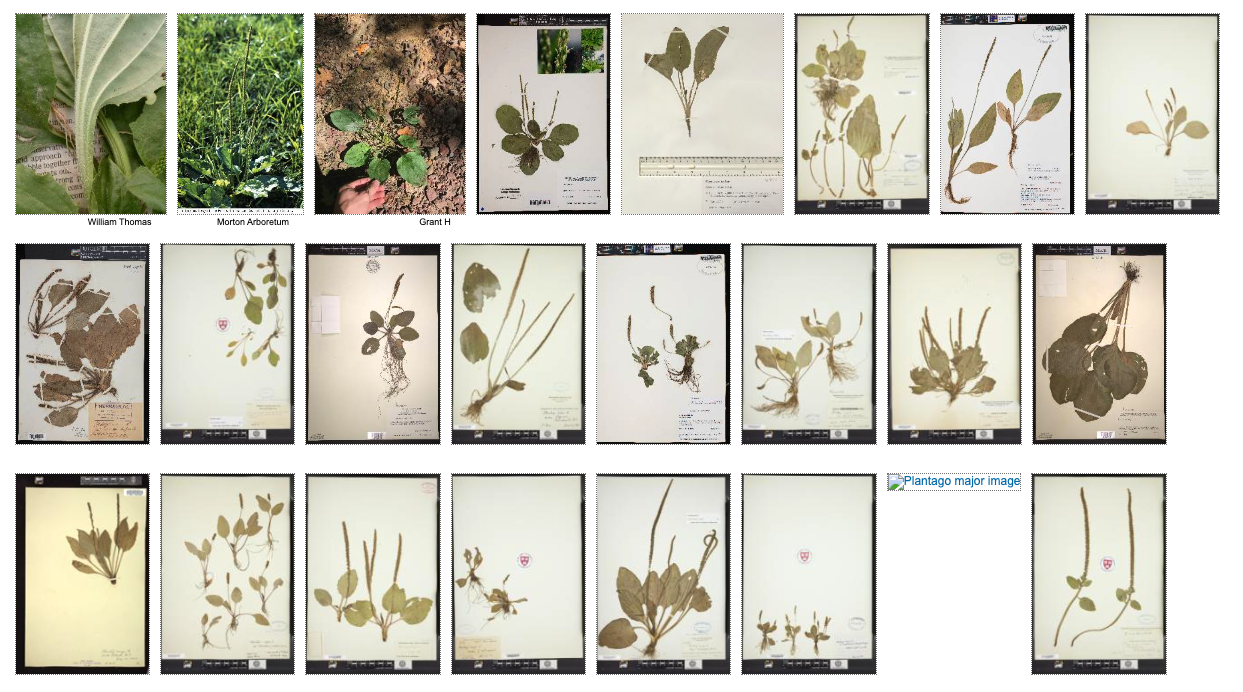

Most of the locations that have preserved plants have more than one. It is interesting to see the variation we get within a single item across the country. Additionally, many of them include habitat notes with the items as well. Just clicking on the scientific name will get you photos of the plant and the first 100 results from the database.

The link for the data base is HERE.

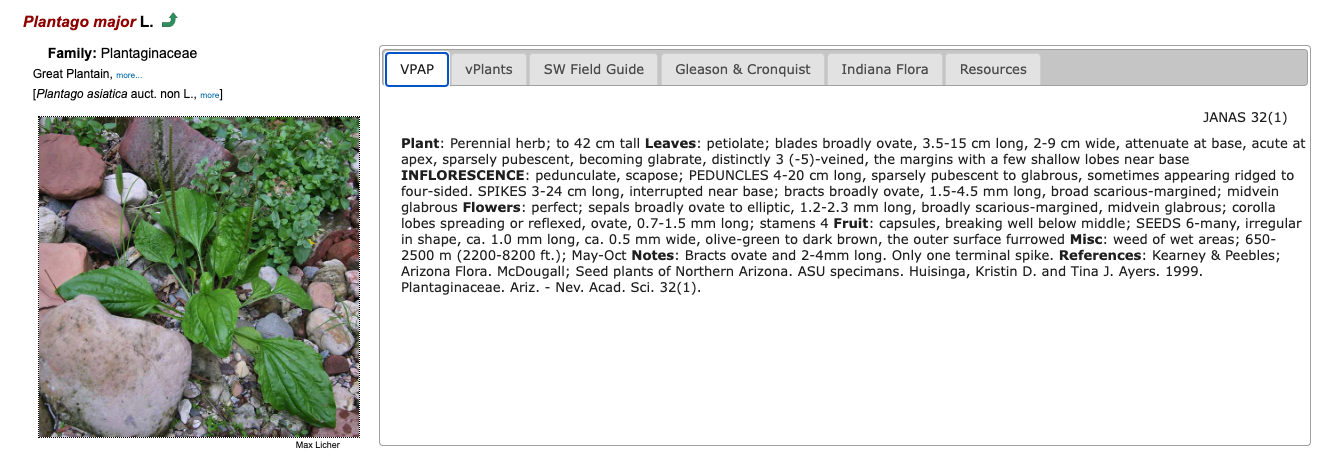

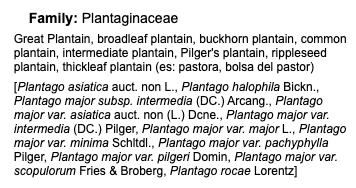

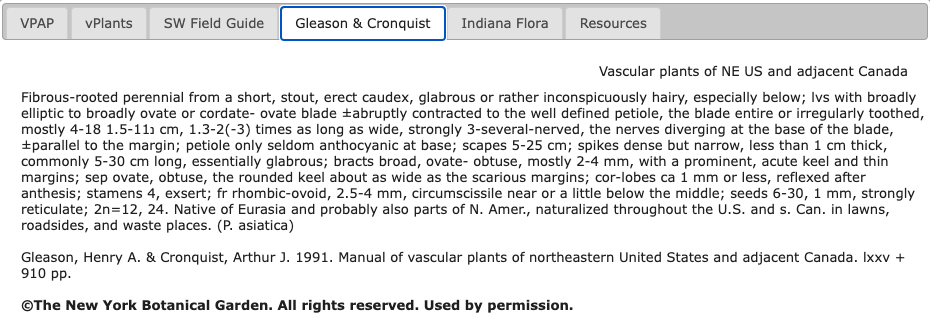

You can see an example of the results for Broadleaf Plantain below.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed