Anglo-Norman Dictionary, University of Aberystwyth. https://anglo-norman.net/anglo-norman.net/

Arsdall, Anne Van. Medieval Herbal Remedies: The Old English Herbarium and Anglo-Saxon Medicine, Routledge, 2010.

Backx-de Groot, Githa. "Historical overview of herbal medicine from ancient to modern times", Utrecht University, 2013.

Biggam, Carole. "Magic and Medicine - Early Medieval Plant-Name Studies", Leeds Studies in English, University of Leeds, 2013.

Black, Maggie. The Medieval Cookbook, The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2012.

Blunt, Wilfrid and Sandra Raphael. The Illustrated Herbal (Manuscripts), Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1979.

Bremness, Lesley. Herbs, Dorling Kindersley, 1994.

Burnett, John. "The Giustiani Medicine Chest", Medical History, Cambridge University Press, 1982.

Cholmely, H. P. John of Gaddesden, Clarendon Press, 1912.

Collins, Minta. Medieval Herbals: The Illustrative Tradtions, The British Library, 2000.

Cogliati Arano, Luisa. The Medieval Health Handbook – Tacuinum Sanitatis, George Brazukker, Inc, 1976.

Dave’s Garden, Plant Files, davesgarden.com

Dictionary of Old English Plant Names, 2007-2022. http://oldenglish-plantnames.org/preface

Dean, Jenny. A Heritage of Color, Search Press, 2014.

Dendle, Peter and Alain Touwaide. Health and Healing from the Medieval Garden, The Boydell Press, 2008.

Everett, Nicholas. The Alphabet of Galen, University of Toronto Press, 2012.

Fitch, John G. On Simples, Attributed to Dioscorides, Brill, 2022.

Frantzen, Allen J. Food, Eating and Identity in Early Medieval England, The Boydell Press, 2014.

Getz, Faye M. Healing and Society in Medieval England, University of Wisconsin Press, 2010.

Hoffman, David. The Complete Illustrated Holistic Herbal, Element, 1996.

Kiple, Kenneth F. The Cambridge World History of Food, Volume 1, Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Kiple, Kenneth F. The Cambridge World History of Food, Volume 2, Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Galen (translation by P.N. Singer). Galen, Selected Works, Oxford University Press, 1997.

Getz, Faye. Healing and Society in Medieval England: A Middle English translation of the pharmaceutical writings of Gilbertus Anglicanus, University of Wisconsin Press, 2010.

Greco, Gina L and Christine M. Rose. The Good Wife’s Guide, Cornell University Press, 2009.

Green, Monica H. The Trotula: A Medieval Compendium of Women's Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, 2001.

Hall, Alaric. "Madness, Medication - and Self-Induced Hallucination? Elleborous (and Woody Nightshare) in Anglo-Saxon England, 700-900", Magic and Medicine: Early Medieval Plant-Name Studies, University of Leeds, 2013.

Henisch, Bridget A. The Medieval Cook, The Boydell Press, 2009.

Hoffman, David. The Complete Illustrated Holistic Herbal, Element, 1996.

Hozeski, Bruce W. Hildegarde’s Healing Plants from her Medieval Classic Physica, Beacon Press Books, 2001.

Hunt, Tony. Popular Medicine in Thirteenth-Century England, Boydell & Brewer, 1990.

Hunt, Tony. Plant Names of Medieval England, D.S. Brewer, 1989.

Hunt, Tony. Three Receptaria from Medieval England, The Society for the Study of Medieval Languages at Oxford, 2001.

Landsberg, Sylvia. The Medieval Garden, University of Toronto Press, 2003.

Lang, S. J. "The 'Philomena' of John Bradmore and its Middle English Derivative: A Perspecitve on Surgery in Late Medieval England", University of St. Andrews, 1998.

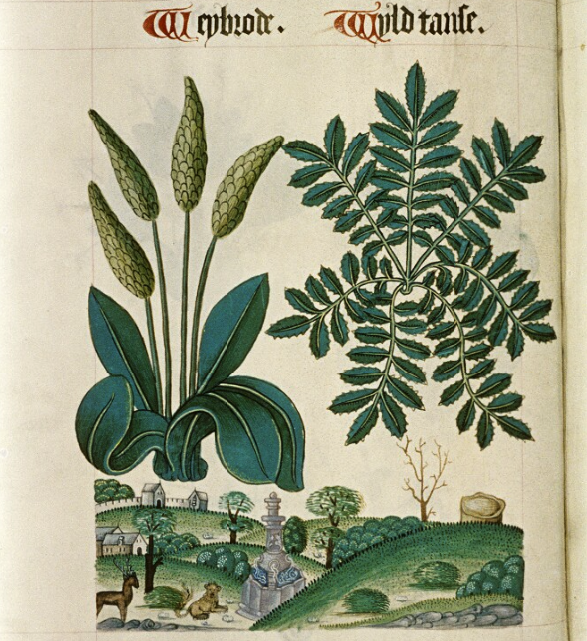

Lonicer, Adam. Kreuterbuch, kunstliche Conterfeytunge der Bäume, Stauden, Kreuter, Getreyde, Gewürtze, was printed in Franfort by Christian Engenolph, 1587. (Additional versions of this book were still being printed into the 18th century.)

Mabey, Richard and Michael McIntyre. The New Age Herbalist, Collier Books, 1998.

Mäkinen, Martii. "Between Herbals et alia: Intertextuality in Medieval English Herbals", University of Helsinki, 2006.

Matterer, James L. Tacuinum Sanitatis in “Gode Cookery”, 2009. http://www.godecookery.com/tacuin/tacuin.htm

McKerracher, Anglo-Saxon Crops and Weeds, Archaeopress Publishing, 2019

Meyer, J. E. The Herbalist, Meyer, 1960.

Middle English Compendium, University of Michigan, 2022. https://quod.lib.umich.edu/m/middle-english-dictionary

Mirrione, Claudia. "Theory and Terminology of Mixture in Galen", University of Berlin, 2017

Mount, Toni. Medieval Medicine, Amberley Publishing, 2016.

Mortimer, Ian. The Time Traveler’s Guide to Medieval England, Touchstone, 2008.

National Audubon Society. National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Wildflowers, Knopf, 2001.

Norri, Juhani. Dictionary of Medical Vocabulary in English, 1375-1550, Ashgate, 2016.

Obaldeston, Tess Ann (Editor), Pedanius Dioscorides (Author), Dioscorides: De Materia Medica, Ibidus Press, 2000.

Paavilainen, Helena M. Medieval Pharmacotherapy: Continuity and Change, Brill, 2009.

Pavord, Anna. The Naming of Names, Bloomsbury USA, 2005.

Peterson, Lee and Roger Tory Peterson. A Field Guide to Edible Wild Plants of Eastern and Central North America, Houghton Mifflin, 1978.

Petrides, George A. and Janet Wehr. Peterson Guides - A Field Guide to Eastern Trees: Eastern United States and Canada, Houghton Mifflin, 1998.

Pettit, Edward Thomas. A critical edition of the Old English Lacnunga in BL MS Harley 585, King’s College London, 1996.

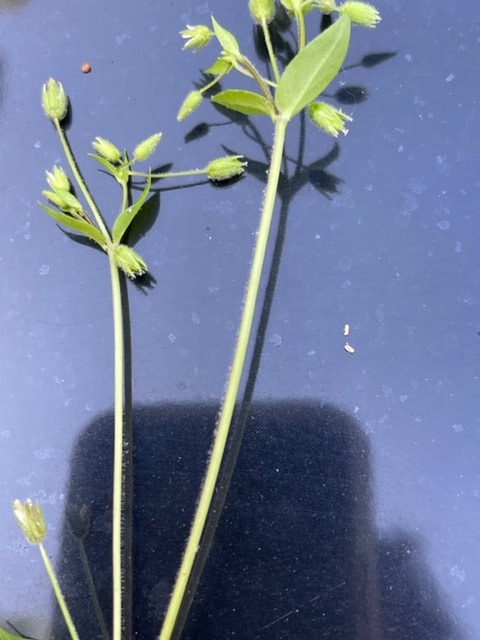

Plantnet.org. Plant identification application.

Pollington, Stephen. Leechcraft: Early English Charms, Plantlore and Healting, Anglo-Saxon Books, 2011.

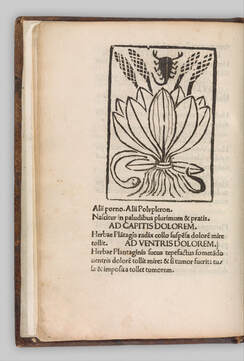

Pseudo-Apuleius Platonicus (4th Century CE), 1428-1500, Publisher - Johannes Philippus de Lignamine, 1428-1500. Metropolitan Museum of Art: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/365881

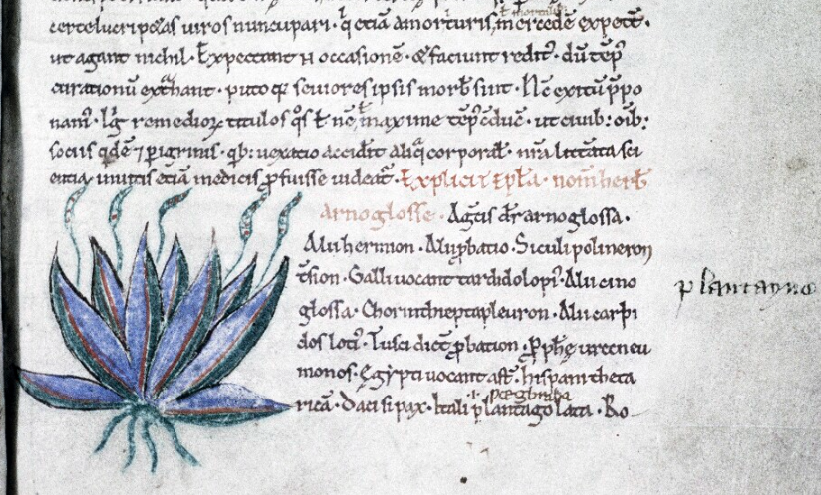

Pseudo-Apuleius Platonicus (4th Century CE), Bodleian Library MS. Ashmole 1431, 1070-1100, Canterbury, Digital Bodleian. https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/objects/98127ed0-4bde-41e0-a93a-98a185b01de8/surfaces/3ec57965-769e-4ed2-8573-16fe862c7d49/

Redon, et. al. The Medieval Kitchen – Recipes from France and Italy, University of Chicago Press, 1993.

Reed, Zsuzsanna Papp. "'Other Plants I Can't Name for You in English': The Plant Composition of Monastic Herb Gardens in Late Medieval England".

Singer, P.N. and Philip J. van der Eijk. Galen: Works on Human Nature - Volume 1 - Mixtures, Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Di Gennaro Splendore, B. (2021). The Triumph of Theriac, Nuncius, 36(2), 431-470, Brill.

Sullivan, Karen. The Complete Family Guide to Natural Home Remedies, Element, 1997.

Touwaide, Alain and Peter Dendle. Health and Healing from the Medieval Garden, 2008.

Trease, G. E. and J. H. Hodson. "The inventory of John Hexham, a 15th Century Apothecary", Medical History, Cambridge University Press, 2012.

The Tudor Pattern Book, Bodleian Library MS. Ashmole 1504.

Wildflower.org. Plant Database, The University of Texas at Austin.

Zupko, Ronald Edward. "Medieval Apothecary Weights and Measures: The Principal Units of England and France", Pharmacy in History, Volume 32, Number 2, University of Wisconsin Press, 1990. JStore Link.

A Wandering Elf participates in the Amazon Associates program and a small commission is earned on qualifying purchases. This commission becomes more books! Thank you!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed