When I first started out in the SCA, many people were doing “Early Celt”, especially for Pennsic. I was told the most accurate thing to do was to get homespun cotton (a type of quilting cloth) in plaids and make bogdresses for this look.

Of course, no one ever addressed the fact that “Early Celt” covers a vast range of time and geography. Over a thousand years and more than a dozen modern countries. Most amusedly so, I was presented with the idea that the ultimate attire for the well-to-do “Early Celt” was not only a plaid, but a patchwork garment (preferably with the pieces made of plaid textiles). One image gets used over and over, even now, to illustrate what many believe to be the quintessential Celtic look.

Of course, no one ever addressed the fact that “Early Celt” covers a vast range of time and geography. Over a thousand years and more than a dozen modern countries. Most amusedly so, I was presented with the idea that the ultimate attire for the well-to-do “Early Celt” was not only a plaid, but a patchwork garment (preferably with the pieces made of plaid textiles). One image gets used over and over, even now, to illustrate what many believe to be the quintessential Celtic look.

I am only going to briefly address my thoughts on patchwork/piecework clothing in early history. I am also not going to make any sweeping statements that this was “never” done, but it is not something for which I have seen much evidence, especially for a status garment. (We do have items like the Bernuthsfeld tunic, which has been extensively repaired to the point that it is nearly entirely patchwork at this point.). My rationale for “patchwork” garments not being much of a fashion is pretty extensive.

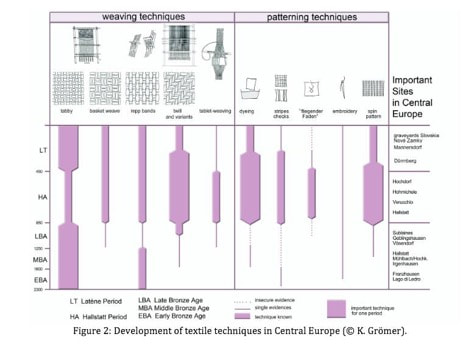

Fortunately, I already have great resources such as Karina Grömer’s work on Central Europe to help paint a better picture of period textiles. In her paper “Textiles Materials and Techniques of Central Europe in the 2nd and 1st Millennia BC” she has the following absolutely fabulous chart.

- The time commitment to sewing and weaving in early periods is exceptional. It takes months to craft the cloth for a single garment. While you would use every scrap of that cloth, many things would be woven to fit a need (and not create waste). Scraps could also be used for other purposes as well, or small pieces for hats, mittens, childrens’ clothing, bags, etc. All are necessary items.

- Piecework is another time sink. Hand sewing so much cloth would detract from the time needed to spin and weave to cloth other members of the family.

- Piecing changes the drape of the cloth and adds bulk. Status clothing, even this early, could made from be exceptionally fine textiles. Why would anyone want to change the beautiful drape that is a product of so much labor by chopping it up and piecing it?

- I think images like this were merely a fantasy of what chequered cloth referred to in historical record could mean.

- I also strongly suspect that the Brehon laws of Ireland come into play here, but this is something that should be considered in context of time, place, and culture.

Fortunately, I already have great resources such as Karina Grömer’s work on Central Europe to help paint a better picture of period textiles. In her paper “Textiles Materials and Techniques of Central Europe in the 2nd and 1st Millennia BC” she has the following absolutely fabulous chart.

This item beautifully illustrates the shift in trends from things like a dominance of twills during the Hallstatt period to the later prevalence of tabby textiles by the end of the La Tene period (450-1BCE). This also shows us the relative rarity of embroidery (something that I addressed recently here http://awanderingelf.weebly.com/blog-my-journey/ancient-embroidery-or-the-lack-thereof ), and the thing most pertinent to this discussion, stripes and checks in textiles.

The popular image of the early Celt, especially in the SCA, is that of a person who wears plaid tunic, pants, and cloak. Articles even often feature this image of ancient textiles as source for historic Celtic plaids. The compilation is not “wrong” but it certainly lacks context when it is used.

The popular image of the early Celt, especially in the SCA, is that of a person who wears plaid tunic, pants, and cloak. Articles even often feature this image of ancient textiles as source for historic Celtic plaids. The compilation is not “wrong” but it certainly lacks context when it is used.

According to Grömer’s chart, stripes and checks were a known technique in the Hallstatt period, but not an “important” one (it is not a dominant technique for the time). This holds for the early La Tène period, but tapers off to the “single evidence” category after that.

In Grömer’s other works, such as her book The Art of Prehistoric Textile Making, she discusses that during the La Tène period, the favor also shifts from warp stripes as a result of textile production becoming an industry, rather than merely domestic work to fill a family’s needs.

All of this results in me asking many questions, the foremost of which is exactly HOW much in the way of stripes or plaids should I be incorporating in a single costume. I am hoping the La Tene textile chart I am working on will answer that once the rest of my books arrive from Germany, but for the time being, I decided to take a more critical look at some of the Hallstatt textiles, because I do already have that material on hand.

First let me state that the book Textiles from Hallstatt is nothing short of amazing. I love this volume, and the work that went into it. The book discuses textiles, textile production, costume and then has a catalog (with excellent photos and highly detailed information) on the textiles. Each fragment is categorized in a number of ways, including by weave, presence of dye, if there are seams, if it is spin-patterned or woven as a color pattern and if it is cloth, band, or cord.

I am looking at this from a different perspective than the author who is doing the scientific work of categorizing the textile fragments. I am viewing this as a reenactor trying to determine the most appropriate fabrics for a kit, and added an additional two categories. In book’s definition of “Pattern”, textiles with different colored warp and weft threads are included (an example would a cloth with a completely yellow warp and brown weft). This is definitely a way of creating visual interest in a garment, but it is very different than weaving in a color pattern that shows as a stripe or check. Therefore, I created a separate category for those items.

The other change I have made is to separate out “speckeled” textiles. Sometimes Grömer lists these as a Pattern, sometimes not. These can be a result of using threads that include both light and dark fibres (giving a tweed like appearance) or it can be by using yarns of different shades, or perhaps a single yarn that is variegated due to several shades of brown being used to spin it. Sometimes when woven, this will also produce a “speckled” textile (though I prefer the term “visually textured”), but sometimes the way the yarns align on the loom, it reads as stripes. Because these always tend to be in the same color family, and are very random, I have listed them separately from more deliberately patterned stripes and plaids if the textile visually looks more patterned rather than just textured (which also often have much more contrast between colors).

The idea of speckeled textiles is very interesting to me, especially those resulting in less-than-deliberate striping. When ancient authors did mention patterned cloth were they only referring to brightly contrasted intentional patterning, or did this also apply to the naturally pigmented wool that could vary in shade and can appear striped when woven into a garment? Authors such as Johanna Banck-Burgess mentions some of the issues with ancient sources in her book Instruments of Power: Celtic Textiles, these include things such as linguistic issues within the sources and also the fact that some of the ancient authors never traveled to Gaul or elsewhere. Further, many cultures in Europe at the time wore plaids or stripes, which only further muddies the waters here.

The purpose in this exercise is to determine how prevalent the use of deliberate colored stripes and plaids is among the Hallstatt textiles to later compare to the hypothetically lesser use of them during the La Tène period. The book cites that 1/5 of the Hallstatt textiles were patterned. For my survey, I have removed bands and cords from the list of textiles, as well as some of the fragments that were too disintegrated to determine if they were indeed previously cloth or cord. I also am ONLY including items from the Iron Age body of work. If two different textiles are sewn together, I count them separately.

Also important to note is the fact the patterned fabrics from this site are only two colors (bands might be three colors). Some of the Durrnberg textiles are three (and I hope to determine what percentage of those are three verses two once the resources arrive).

My categories are as follows:

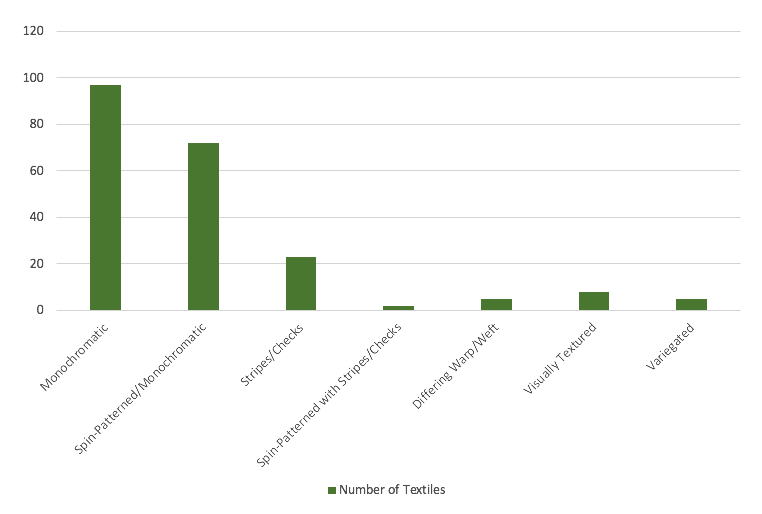

The chart below shows the number of textiles in each category.

In Grömer’s other works, such as her book The Art of Prehistoric Textile Making, she discusses that during the La Tène period, the favor also shifts from warp stripes as a result of textile production becoming an industry, rather than merely domestic work to fill a family’s needs.

All of this results in me asking many questions, the foremost of which is exactly HOW much in the way of stripes or plaids should I be incorporating in a single costume. I am hoping the La Tene textile chart I am working on will answer that once the rest of my books arrive from Germany, but for the time being, I decided to take a more critical look at some of the Hallstatt textiles, because I do already have that material on hand.

First let me state that the book Textiles from Hallstatt is nothing short of amazing. I love this volume, and the work that went into it. The book discuses textiles, textile production, costume and then has a catalog (with excellent photos and highly detailed information) on the textiles. Each fragment is categorized in a number of ways, including by weave, presence of dye, if there are seams, if it is spin-patterned or woven as a color pattern and if it is cloth, band, or cord.

I am looking at this from a different perspective than the author who is doing the scientific work of categorizing the textile fragments. I am viewing this as a reenactor trying to determine the most appropriate fabrics for a kit, and added an additional two categories. In book’s definition of “Pattern”, textiles with different colored warp and weft threads are included (an example would a cloth with a completely yellow warp and brown weft). This is definitely a way of creating visual interest in a garment, but it is very different than weaving in a color pattern that shows as a stripe or check. Therefore, I created a separate category for those items.

The other change I have made is to separate out “speckeled” textiles. Sometimes Grömer lists these as a Pattern, sometimes not. These can be a result of using threads that include both light and dark fibres (giving a tweed like appearance) or it can be by using yarns of different shades, or perhaps a single yarn that is variegated due to several shades of brown being used to spin it. Sometimes when woven, this will also produce a “speckled” textile (though I prefer the term “visually textured”), but sometimes the way the yarns align on the loom, it reads as stripes. Because these always tend to be in the same color family, and are very random, I have listed them separately from more deliberately patterned stripes and plaids if the textile visually looks more patterned rather than just textured (which also often have much more contrast between colors).

The idea of speckeled textiles is very interesting to me, especially those resulting in less-than-deliberate striping. When ancient authors did mention patterned cloth were they only referring to brightly contrasted intentional patterning, or did this also apply to the naturally pigmented wool that could vary in shade and can appear striped when woven into a garment? Authors such as Johanna Banck-Burgess mentions some of the issues with ancient sources in her book Instruments of Power: Celtic Textiles, these include things such as linguistic issues within the sources and also the fact that some of the ancient authors never traveled to Gaul or elsewhere. Further, many cultures in Europe at the time wore plaids or stripes, which only further muddies the waters here.

The purpose in this exercise is to determine how prevalent the use of deliberate colored stripes and plaids is among the Hallstatt textiles to later compare to the hypothetically lesser use of them during the La Tène period. The book cites that 1/5 of the Hallstatt textiles were patterned. For my survey, I have removed bands and cords from the list of textiles, as well as some of the fragments that were too disintegrated to determine if they were indeed previously cloth or cord. I also am ONLY including items from the Iron Age body of work. If two different textiles are sewn together, I count them separately.

Also important to note is the fact the patterned fabrics from this site are only two colors (bands might be three colors). Some of the Durrnberg textiles are three (and I hope to determine what percentage of those are three verses two once the resources arrive).

My categories are as follows:

- Monochromatic: This cloth has the appearance of a solid color textile. Included here are some textiles that might have a variation in shade but that still appears somewhat uniform from a distance.

- Spin-Patterned: Spin-patterning uses threads of both S and Z twist woven together to create patterns of stripes or checks that reflect light differently. This category all uses a single color of yarn only.

- Visually Textured: This cloth uses fibres of varying shades in the threads that results in a speckeled or tweed-like appearance. It is still monochromatic, but the result has more of a textured appearance than a solid-colored textile.

- Variegated: These textiles uses random light and dark threads of the same color (usually brown), or possibly variegated threads that are spun from several shades of the same color of wool. Weaving sometimes results in a subtle, random stripe in the cloth.

- Differing warp and weft: The threads in these two systems are different colored. In some cases there is a strong light/dark contrast as a result, in one olive textile, the result is more subtle.

- Stripes/Checks: This cloth is deliberately patterned with either stripes or checks of a contrasting color.

- Spin-Patterning and Stripe/Check: These textiles use both spin-patterning and deliberate contrasting stripes or checks as a design feature.

The chart below shows the number of textiles in each category.

Further, if you add all of the monochromatic textiles (both plain and spin-patterned) as well as those that only present a tweed-like texture (rather than a monochromatic pattern), we are looking at 83.4% of the textiles being essentially solid-colored. 11.7% are striped/checked. 2.3% have different colored warp and weft and 2.3% have variegated stripes.

The vast majority of the textiles from this site are solid. I look forward to seeing the Durrnberg material as well, to compare to this data (as well as that from other La Tene period sites). I am, however, already starting to believe that while stripes and checks were in use by the early Celtic cultures, that they are not as prevalent as myth would have us believe.

The vast majority of the textiles from this site are solid. I look forward to seeing the Durrnberg material as well, to compare to this data (as well as that from other La Tene period sites). I am, however, already starting to believe that while stripes and checks were in use by the early Celtic cultures, that they are not as prevalent as myth would have us believe.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed