A number of Viking Age graves, particularly those from 10th Century Birka, contain fragments of finely pleated linen, presumed to be remnants of an under gown. This type of cloth is frequently associated with Birka, where 52 graves were identified as containing linen serks, and of those 21 were showed evidence of having been finely pleated. (Thunem, Serk) Birka was not the only location of such textiles, as there was a pleated linen shirt in Hedeby grave 5/1964. (Hägg, Textilien, 325). Pleated linen shirts are also found in grave goods from sites in Russia, the best examples of which are Gnezdovo and Pskov.

Agnes Geijer, who did the original work with the Birka textiles, revised her thoughts on the local origin of linen garments to acknowledge Inga Hägg’s theories that not only the textiles, but likely the garments themselves were imported as ready made items from Kiev. Geijer also notes that she believes it possible that unpleated serks at Birka might well just represent cloth from which the pleating has been washed out and that more of shirts might originally have born pleats. (Geijer, Textile Finds, 88)

Grave 5/1964 from Hedeby had remains of a Slavic style pleated shirt outside of the wagon in the entombment. Inga Hägg comments that “some fragments of pleated shirts found at Hedeby might be associated with the dress of women belonging to the Slavic aristocracy”.

Many reconstructions I have seen rely on methods of pleating that become undone when the garment is washed. Included in these are to use a needle and thread to draw the fabric into pleats that run the whole length of the body, but not using any strings to fix the pleats permanently (very time consuming to have to repeat each time) and the “broomstick” method that involves tightly binding or twisting the garment while wet and allowing it to dry, which causes creases to form in the garment (the pleats in this method do not seem that they would follow arc formed by the pleats in the Birka example, and again, the pleating is not permanent). There have also been interesting methods of construction associated with some of these reconstructions, including those that rely on Eura dress patterning (an item I question with to begin with, because it makes little sense for me to base Finnish wool dress on a leather garment from many centuries prior).

My understanding of the the time involved in spinning and weaving, as well as other daily tasks in period, makes me consider it unlikely that these garments would have used methods that needed to be repeated every time the item was washed. For my reconstruction, I choose to look for permanent methods of fixing the pleats. Because of the prevailing theories on the source of the garments, I also opt to look to the Slavic and Russian sources, to attempt to define the construction methods.

Textile Evidence: Birka

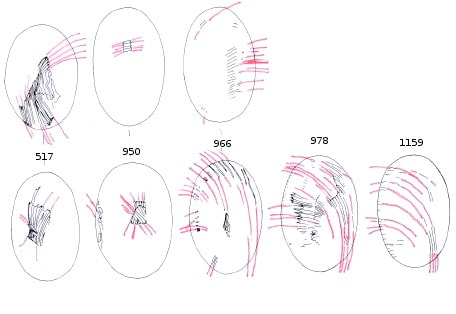

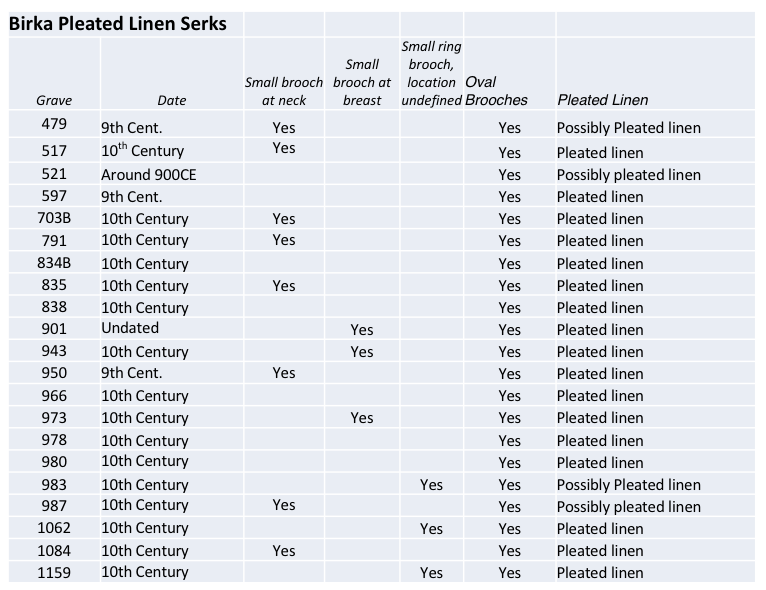

Remains of the pleated dresses at Birka tend to be fragments of textiles preserved because of their proximity of the large oval brooches in the grave. Because textile finds were not always properly categorized at the time of the original Birka excavations, there is some question as to the position of the brooches in the grave (nor do we know which was right or left). This leads to various interpretations of the garment because one cannot state for sure the direction of the pleats. Another factor that can compound this mystery is the tendency of the brooches to shift as the body decomposes, which could pull the pleats out of their normal alignment. Hilde Thunem notes in her research on the serk that the pleats tend to run parallel the the brooch needle and then bend to one side. Without knowing which brooch is right or left, this could mean that the pleats fan out from a neckline or possibly run along the body and bend towards the arm.

There is one additional bit of evidence that can help aid in forming a reconstruction, and that is the and that is linen fragments that are preserved by metal objects laying along side the body in the grave. Grave 1062 from Birka shows pleats running horizontally on the arm but bears no evidence of pleating within the brooches themselves. (Hägg, Kvinnodräkten, 17)

The Birka linens average 38-51 threads to the inch with a balanced weave.

Despite the fact that the pleats remaining in the Birka brooches are often difficult to read in older photographs, it appears that the pleats are regular and often form firm lines. They are the less ordered “wrinkles” as you would see in a “broomstick skirt” type of pleating.

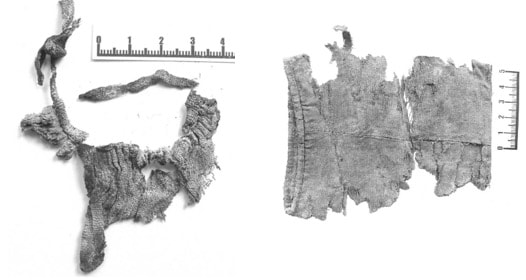

Textile Evidence: Gnëzdovo (Burial Ц-301) and Pskov (Ц-06-CtB3IV)

The garments from these finds are both crafted of linen that have folds at the neck and a sewn on “cord” or bolster at the collar. Pskov used that cord as a tie while there is no fastener noted in the other example. The fragments of the Pskov garment are all dyed blue, while Gnëzdovo has varying qualities of cloth, as well as both blue and possibly undyed textile, as part of its construction. (Orfinskaya and Pushkina, Gnëzdovo, 45-48)

Iconic Evidence

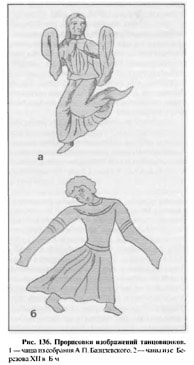

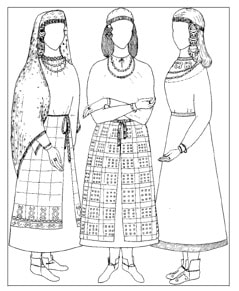

In addition to textile remains, I have looked at some pictorial evidence that suggest the chosen elements of my recreation. Long sleeves, often wumpled at the wrists, are seen in imagery from various Russian sources, including drinking vessels. This is also a fashion that shows up repeatedly in Saxon illumination during the Viking Age as well.

One of the most interesting items that seems to show a dress with vertical pleats on the front, long tapered sleeves that fall into folds up the arm is the Revninge Figure found in eastern Denmark in 2014. Though believed to be of Viking manufacture, the costume is strikingly like proposed recreations of Slavic costume that show a panova (poneva) skirt and pleated garment with long sleeves pushed up at the wrist to form folds.

For my reconstruction, I worked with a tightly pleated neckline such as was seen in the Pskov fragment, as well as tapered sleeves found there. Having the pleating drawn up by a thread (in my case, three, similar to the Gnëzdovo waist pleats) allows me to have a permanent pleating structure that does not need to be reset after the garment is washed. My pleats are approximately 6mm deep and very compact (I tried to gauge the size and number of pleats in the Pskov fragment based on the scale in one of the articles). At the moment, the neckband also serves as a tie, but I might eventually replace the tie with a small brooch (as that seems to be an available option based on the number of Birka graves that contain both a pleated serk and a small brooch at the neck). This type of pleating conforms to direction alignment of some of the pleats found in brooches from Birka.

I opted for the overly long sleeves seen in Russian art and in the Revninge Figure. This choice allows for creases to form up the arm that round around the arm, rather than running along the length of it, conforming with the evidence of Birka 1062. Again, this type of creasing does not require continued effort on part of the wearer. After washing the creases will fall out, but even wearing the garment for a short span of time will allow the creases to reform.

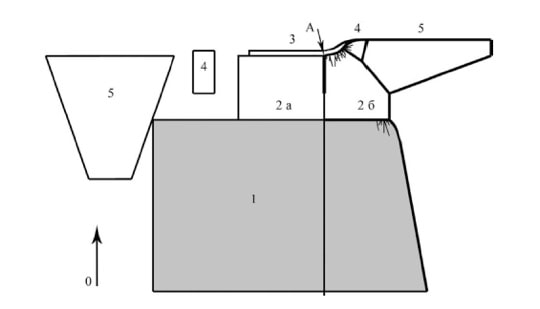

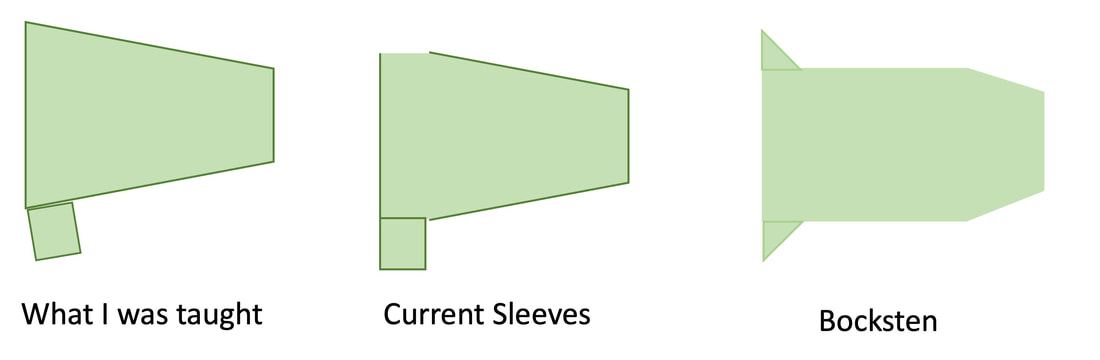

I opted, at this time, for the simplest pattern possible, that uses rectangular construction with little or no waste. I based my garment on a diagram by D. Rushworth. I did extend the length of the sleeves. In my garment, the sleeves were cut as a rectangle the width I wanted, and then tapered after the fact. When I attempt to craft another garment like this, I will cut out the sleeve shape and use the excess from either side to form gores for the body (and make it a bit less wide, with less tightly stacked pleating in the neckline).

On thing that bothers me a bit about some of the diagrams from Hagg’s work with the Birka pleated linen as that it appears that some of the pleats might have a more steep curve. While my hypothetical garment conforms to the extant necklines, and some of the proposed paths for creasing, it does not fall in line with a few of the finds. (Though I still wonder how much shifting of items in situ changed the orientation of the pleats as well, as I can see how it could make a curve more extreme.)

Putting on my dress actually helped clarify this for me, to some extent. In the photos of me wearing the dress, I have it on with a wrap-style garment, rather than a more fitted one. The looseness of the over dress allows the linen serk to hang without excessive shifting and bunching up under the arms. Further, my garment is tailored to me. The arm is wide enough to allow movement and the square underarm gusset is placed as high as I can with out it binding. If this garment were made to be sold as is, that gusset might not sit as high. This, plus wearing it under a dress that at least as the top hem being fairly fitted, can create bunching and wrinkles in the under arm and on the chest near it which might affect the direction of the creases. I have not tested the pattern of the wrinkles to any extent, but I look forward to doing so in the future to see if they correspond at all to the diagrams from Birka.

One additional consideration that I might implement into a future design is of “shoulder pieces” which can be seen in later Slavic and Russian shirt designs, and are thought to be possible on the garments from Pskov and Gnëzdovo.

Andersson, Eva. Tools for Textile Production from Birka and Hedeby (The Birka Project for Riksantikvarieambetet), 2003.

Bender Jørgensen, Lise. Northern European Textiles until AD 1000, Aarhus University Press), 1992

Bender Jørgensen, Lise. Prehistoric Scandinavian Textiles, (Det Kongelige Nordiske oldskriftselskab), 1986.

Blindheim, Charlotte, “Drakt og smykker”, Viking 11.

Geijer, Agnes. Birka III, Die Textilefunde aus Den Grabern. Uppsala,1938.

Geijer, Agnes. “The Textile Finds from Birka,” Cloth and Clothing in Medieval Europe (Heinemann Educational Books), 1984.

Hägg, Inga. Die Textilefunde aus der Siedlung und us den Gräbern von Haithabu (Karl Wachlotz Verlag). 1991.

Hägg, Inga. Die Textilefunde aus dem Hafen von Haithabu (Karl Wachlotz Verlag). 1984.

Hägg, Inga. Textilien und Tracht in Haithabu und Schleswig. Die Ausgrabungen in Haithabu 18 (Karl Wachlotz Verlag), 2016.

Hägg, Inga, “Kvinnodräkten i Birka: Livplaggens rekonstruktion på grundval av det arkeologiska materialet”, Uppsala: Archaeological Institute, 1974

Hägg, Inga. “Viking Women’s Dress at Birka,” Cloth and Clothing in Medieval Europe (Heinemann Educational Books), 1984.

Hermitage Museum. “Ibn Fadlan’s Journey: Volga Route from Baghdad to Bulghar” , 2016.

Orfinskaya, Olga and Tamara Pushkina. ”10th century AD textiles from female burial Burial Ц-301 at Gnëzdovo, Russia”, Archaeological Textiles Newsletter 53, 2011.

Orfinskaya, Olga. “Льняное платье X века из погребения Ц-301 могильника Гнёздово” (Linen dress from the burial of Ts-301 burial ground Gnëzdovo).

Orfinskaya, Olga and Y. V. Stepanova. “On the Issue of Origins of Russian Dress with Shoulder Straps”.

Stabrova, M.A. Ancient Russian Costume, Nauka Publishers, 1997.

Thunem, Hilde. “Viking Women: Undedress”, 2014. http://urd.priv.no/viking/serk.html

Zubkova, E.S, Orinskaya, O.V, and Mikhailov, K.A. “Studies of the Textiles from the Excavation of Pskov in 2006,” NESAT X, 2009.

Zubkova, E.S, Orinskaya, O.V., and Likhachev, D. “New Discovery of Viking Age Clothing from Pskon, Russia.” (Notes and summary by Perer Beatson) http://members.ozemail.com.au/~chrisandpeter/sarafan/sarafan.htm

RSS Feed

RSS Feed