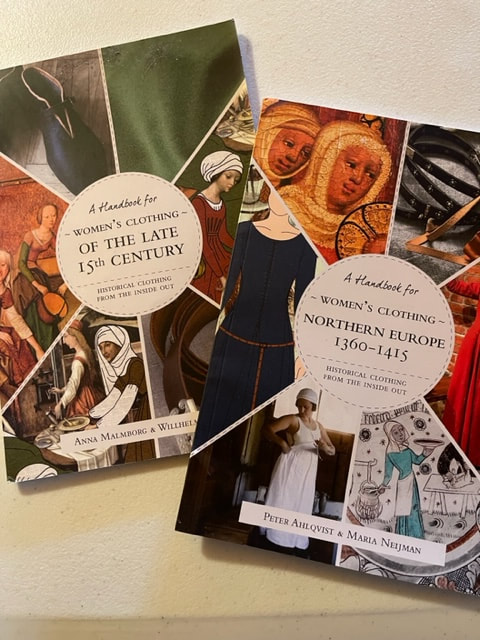

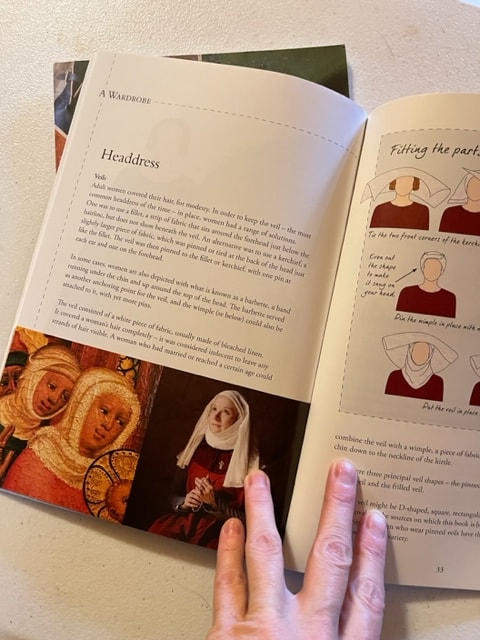

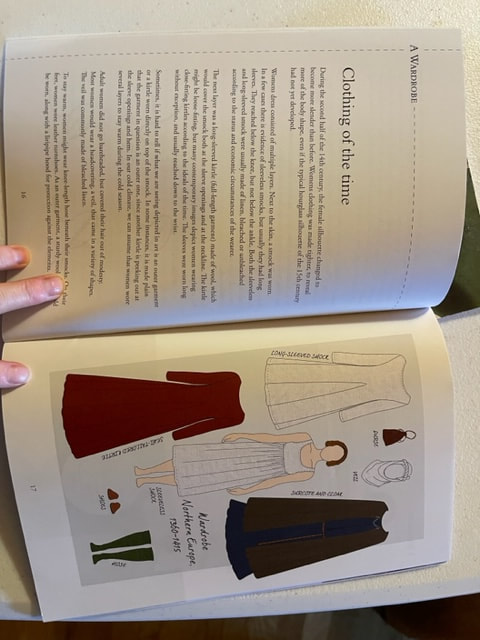

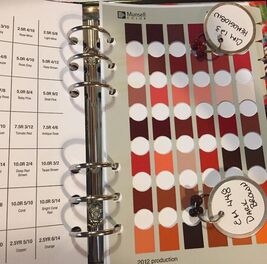

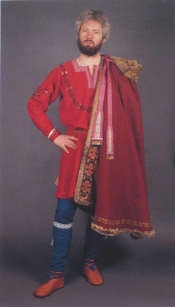

What I like about these books is that they are brief and loaded with images. They pretty simply show the silhouettes and basic construction for the garments, and give necessary details on colors, cloth, and accessories.

I know that the Medieval Tailor's Assistant covers much of this as well, but seeing it in a VERY compact form is also nice. Even if someone is not interested in going fully period or sewing their entire kit themselves, the images here can help them shop for things that perhaps can give them a look that they desire.

Not everyone wants to research (or research every single thing they do) and guides like this become very handy to help folks fill in the gaps where needed.

You can sometimes get these on Amazon, but they are also available from the publishers site (Chronocopia Press). https://chronocopia.se/

15th Century Women's https://amzn.to/49GKz7M

15th Century Men's https://amzn.to/3NThflr

1360-1425 Women's https://amzn.to/3QzCLMA

RSS Feed

RSS Feed