267www.academia.edu/35176385/_Dressing_a_Citys_Demeanour_Ottoman_Costume_Albums_and_the_Portrayal_of_Urban_Identity_in_the_Early_Seventeenth_Century_Textile_History_48_no._2_Nov._2017_248-267

|

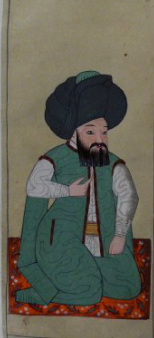

Below is the link to and article that discusses costume albums from 17th century Ottoman Empire. The images are early 17th century and, despite that, are still used frequently by members of the SCA as documentation so I thought I would pass this one on.

267www.academia.edu/35176385/_Dressing_a_Citys_Demeanour_Ottoman_Costume_Albums_and_the_Portrayal_of_Urban_Identity_in_the_Early_Seventeenth_Century_Textile_History_48_no._2_Nov._2017_248-267

0 Comments

This is a fantastic resource to have in your library for Ottoman research for the SCA. You can download it here: http://www.nga.gov/content/ngaweb/research/publications/pdf-library/the-age-of-sultan-sueleyman-the-magnificent.html There are a number of other titles (including several about artists pigments) that can be found on the site as well: http://www.nga.gov/content/ngaweb/research/publications/pdf-library.html  For Atlantia's Holiday Faire event I did my first ever food entry for a competition. The theme was Holiday items so I made Sheker Burek, a sweet dish, served during Ottoman festivals. My documentation and recipe are below. The judges comments were very helpful (they loved my documentation, filling and presentation, but the dough itself was a bit overworked). I will hopefully be revising my methods and trying the recipe again soon. (For the competition I had several pastries laid out on an ornate dish and sprinkled slivered almonds and powered sugar over them. Sheker Burek – A Sweet Dish for Festive Occasions

History Sheker Burek is the ancestor of the the modern börek pastries which are found in Turkey and the nearby region. While the origins of this dish have been suggested to be unleavened flatbreads cooked by nomads on griddles (Malouf, 265), they are today most often comprised of a savory filling encased in dough similar to phyllo. Another modern form of this food has a pasta-like dough that is filled and boiled (Roden, 132). Historically, Muhammed bin Mahmûd Şirvanî, a 15th century Ottoman physician, translated an earlier 13th century cookbook at the request of Sultan Murad II (and in his translation he included an additional eighty recipes) (Samancı, 1981). In this volume of work, the only the sweet version of this burek is mentioned. (Yerasimos, 128) This dessert is also listed in the palace accounts from 1490 and was among the items served at a circumcision feast for Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent’s sons in 1539. (Yerasimos, 128; Samancı, 1981) Occasions such as a royal circumcision were grand festivals, and with books compiled to commemorate these festivities. In these tomes, called surname, were incorporated the details for everything from processions, to the entertainers and to the foods served during the feasting that were part of such grandiose holidays. Also worthy of note, the residents of the 16th century Ottoman Empire had developed a love for sweets that included sweetened rice dishes, fruit preserves, candied nuts and fruit and even included large-scale sugar sculptures that were displayed during festivals. So valued were these sugared dishes that there were even special kitchens on the palace grounds dedicated to the production of sweets. (Yerasimos) A Note Regarding Sources I was fortunate to be able to get two translations of this period recipe from Urtatim al-Qurtubiyya bint 'abd al-Karim al-hakam al-Fassi al-Sayyida from the West Kingdom. She provided me with translated material from Stephane Yerasimos’s French translation of the Şirvanî’s text and also, later, with the modern Turkish translation by Mustafa and Çakır. In addition to those translated passages, I also have the redacted recipe by Yerasimos, but found it no more valuable than the translations of the original recipe in recreating the dessert. (Due to copyrights, I did not include the translations here.) Sheker Burek – My Recipe 3 cups flour 1 cup warm water One packet of yeast and a bit of sugar Salt 4 T butter 100 grams sugar 100 grams almond flour Rosewater Preheat oven to 350. To make the filling, mix together the sugar and almond flour. Sprinkle in just a bit of rose water and mix. The mixture will just stick together and there should not be enough water to make it syrupy. Add a bit of sugar to a cup of warm water and stir in the yeast. Melt butter and add to the flour. Add four pinches of salt. Add the yeast/water to the four and mix until a dough forms. Knead until smooth. Let rest for 15 minutes. Roll out the dough on a floured board and cut into small pieces (I used a coffee cup to make circles from the dough 3-4 inches in diameter). Add a spoonful of the filling to the center of the circle and fold in half. Use a fork to press the edges closed. Add the sheker burek to a cookie sheet greased with butter and back until the tops are just start to brown. Issues with Recreation and My Adaptations/Changes

Sources Cited Argunşah, Mustafa and Müjgan Çakır. Yüzyıl Osmanlı Mutfağı, (Urtatim al-Qurtubiyya bint 'abd al-Karim al-hakam al-Fassi, West Kingdom/ Ellen Perlman, Trans.) Istanbul. 2007., Malouf, Gred and Lucy. Turquoise: A Chef’s Travels in Turkey. Chronicle Books, 2008. Roden, Claudia. The New Book of Middle Eastern Food. Random House, 2008. Samancı, Özge. “Food Studies in Ottoman-Turkish Historiography.” Writing Food History: A global Perspective. (Ed. Clafin and Scholliers.) Berg, 2013. Yerasimos, Stephane and Belkis Taskeser. A la table du Grand Turc. (Urtatim al-Qurtubiyya bint 'abd al-Karim al-hakam al-Fassi, West Kingdom/ Ellen Perlman, Trans.) Sindbad/Editions Actes Sud, 2001.  Atlantian 12th Night was lovely. The site itself was absolutely perfect for the Ottoman theme of the event and there were tons of rooms and spaces for all manner of the activities that happened throughout the day. The food was very good, especially the mushroom-cheese pastries and the meat dumplings. My favorite thing about the event was, as always, getting to hang out with friends. Quite a few folks from my household were there, and I also got to spend time with some people I only see at war and a few new friends who share my geeky tastes in projects! ETA - Now that I am not so tired from the event, I have to comment that the garb at this event was outstanding. SO many people made garb that fit with the theme (and for many of them it was their first Ottoman attire ever) and there was a very nice, period feel to the entire event because of the effort of many people in their dress. It makes me genuinely happy to see how far Middle Eastern garb has come in the SCA!

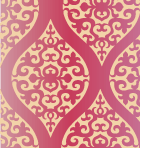

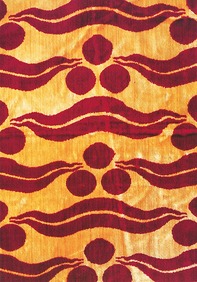

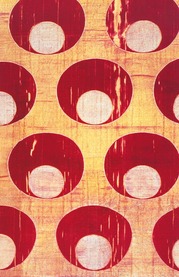

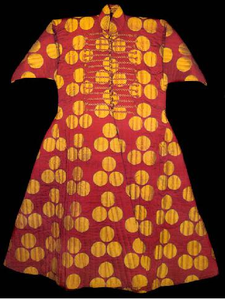

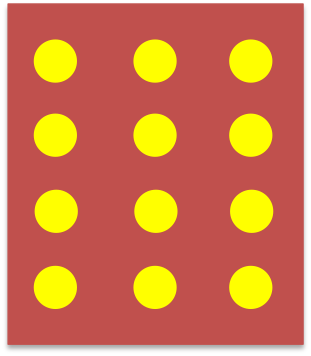

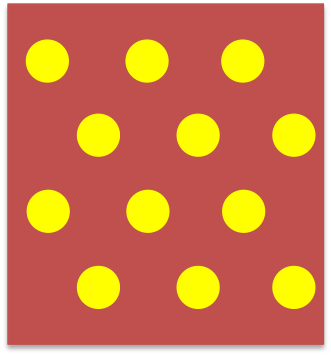

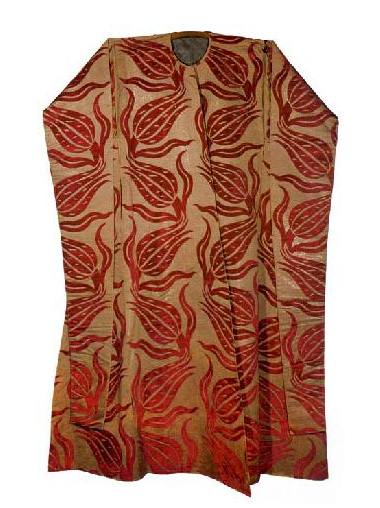

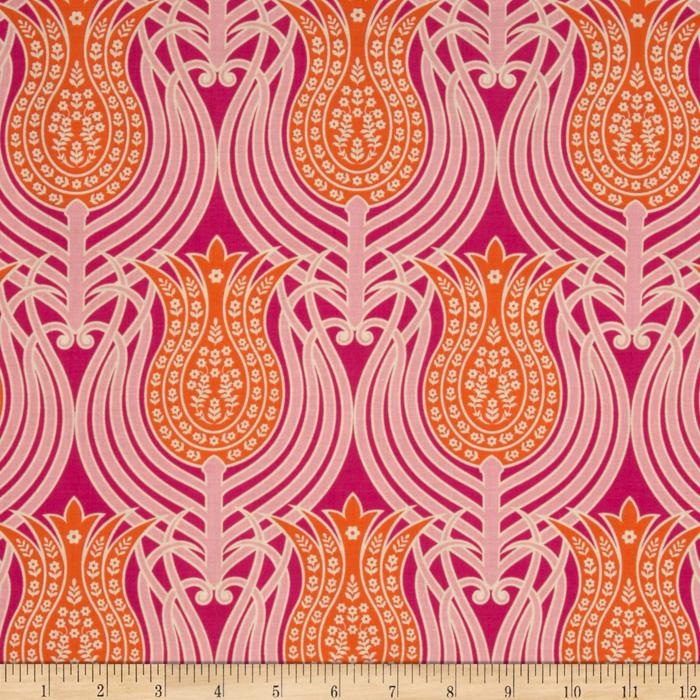

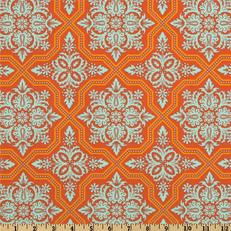

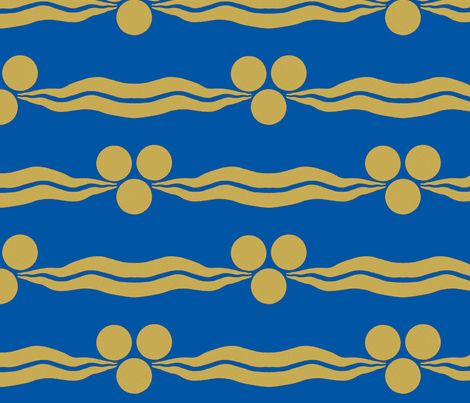

At the end of the third article in this series, I alluded to the fact that creating your own patterned fabric was a very viable option for getting the right look for Ottoman garb and for avoiding the over-wrought look of patterning in most modern fabrics. This post will show some examples of fabulous work done by other members of the SCA who are exploring these methods of fabric ornamentation. Weaving your own textiles is quite feasible for someone pursuing other areas of interest in the SCA (such as Norse), but it would be an immense undertaking (financially and in terms of time) to do so for Ottoman fabrics. There are, however, other ways to get that "look" without creating the fabric from scratch. Some of these methods are stenciling, block printing, debossing, applique and gilding. Some of these techniques are period (gilding, debossing and applique) and others just help us to achieve fabrics patterned with appropriately period motifs. I also have to take a moment to note that any of these methods make it easy to achieve the really BOLD look of period patterning without the superfluous squiggly design elements that tend to show up in our modern printed fabrics. Busy and Bold are not necessarily the same thing, and learning to see the separation in the two is key to recognizing the more period looking fabrics. Stenciling  Photo credit: Mery of Ellersly Photo credit: Mery of Ellersly I have stenciled textiles before and find the process to be a relatively simple one that offers excellent results. I have not, however, done fully stenciled fabric for Ottoman costuming so will feature here a very lovely piece by Mery of Ellersly. I think this piece is a great example of the contrast and scale you often see in period Ottoman textiles. Further, it is linen, so the garment will be quite comfortable and likely will get plenty of wear at SCA events. Typical Ottoman motifs such as crescents, cintamani, 'tiger stripes', and stylized tulips can easily create bold forms and make for excellent garb fabric. Stencil Planet also has several large-scale motifs meant for covering walls that I think would work splendidly for Ottoman garb. Below left are two that I particularly like (I own one of them... just need the time to use it)! This store also does custom orders for those not willing to cut out their own stencils. They are fast and do a great job with this (I have used them before for custom Viking stencils). Stencil Library is another source of stencils that has a broad selection that includes some that would work well for garb. Below right is just one of the lovely designs they offer. Sites such as Dharma Trading carries textiles paints suitable for stenciling techniques. Block Printing  Photo credit: Bushra al Jaserii bint El Nahr Photo credit: Bushra al Jaserii bint El Nahr Bushra al Jaserii bint El Nahr, Avacal An Tir, has been working with block printing fabrics and has created some very appealing textiles that favor the bold, stylize motifs that are so common in the Ottoman world. A PDF of her tutorial can be found at the link above the images of her fabulous fabrics pictured below! Blocks for printing can be self-made or purchased online at a variety of places, including Etsy (there are some vendors that will even create custom stamps for you). Look for large scale, bold designs when purchasing a stamp, or ask to have one custom made in a pattern that you know is period. http://www.etsy.com/shop/BlackleafArt http://www.etsy.com/shop/charancreations Sites such as Dharma Trading has information on fabric painting and decoration and can be a great resource for supplies.

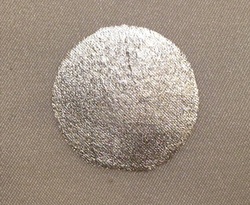

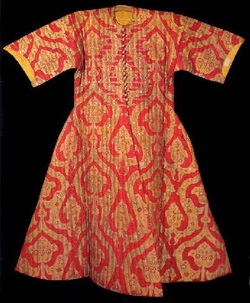

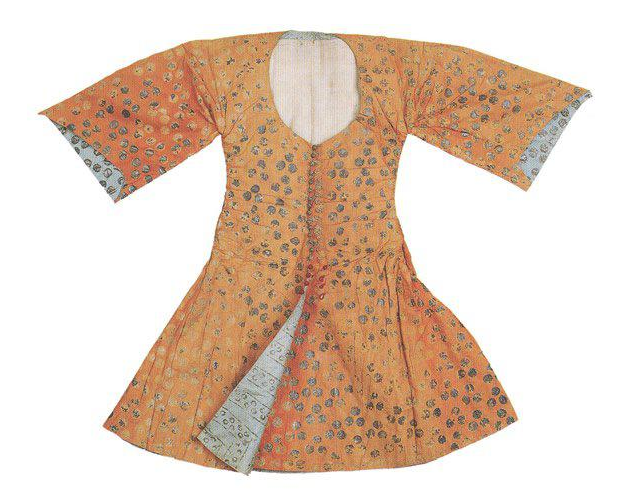

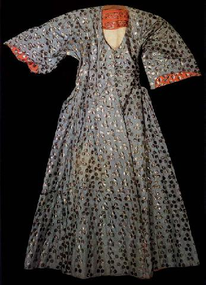

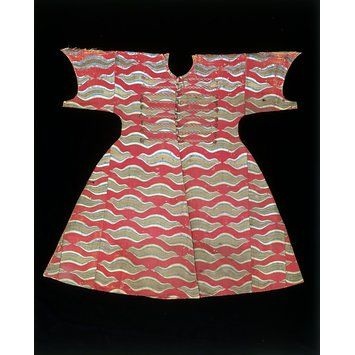

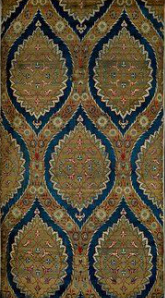

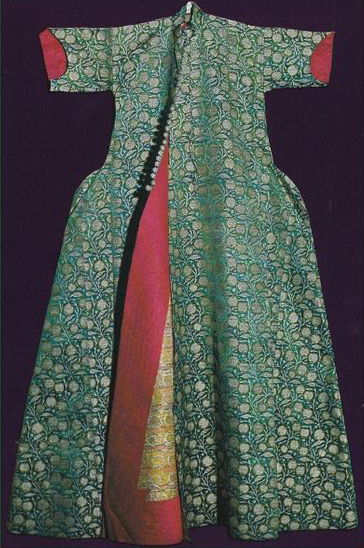

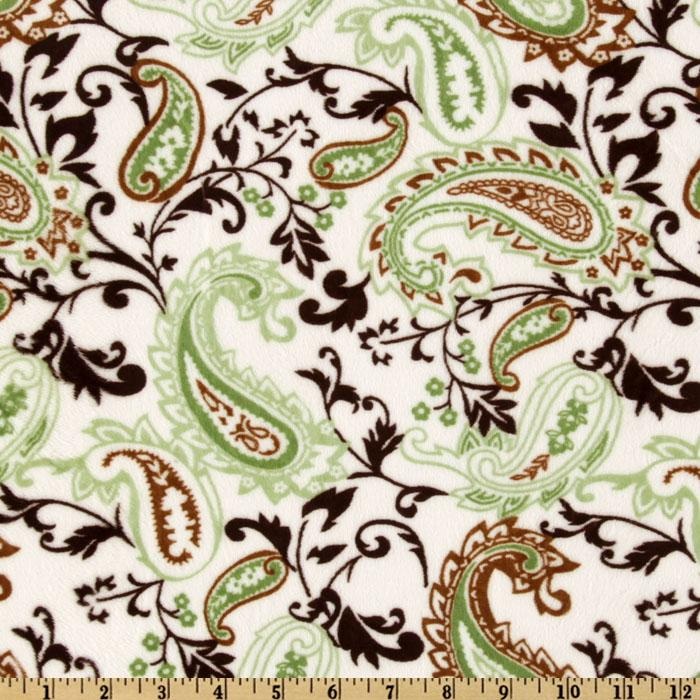

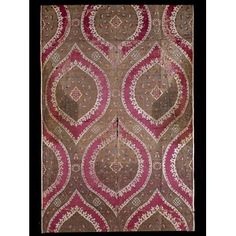

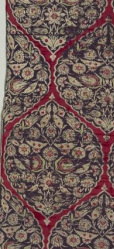

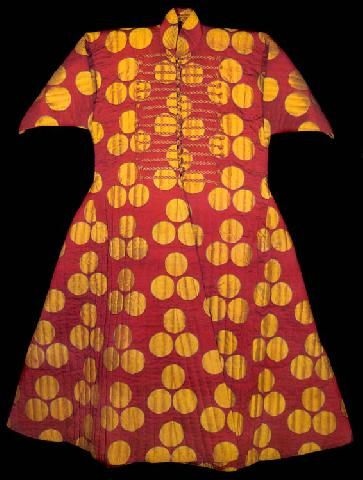

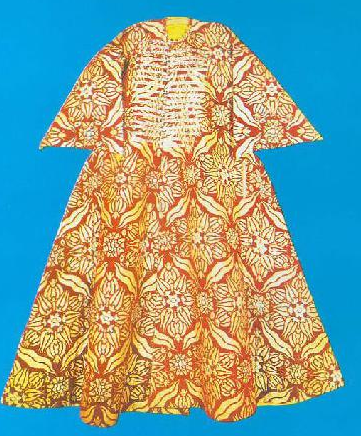

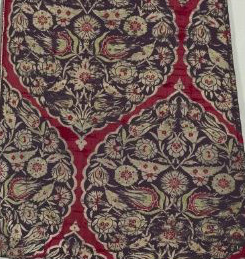

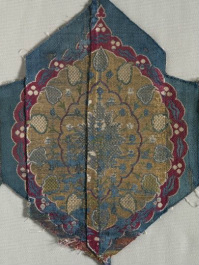

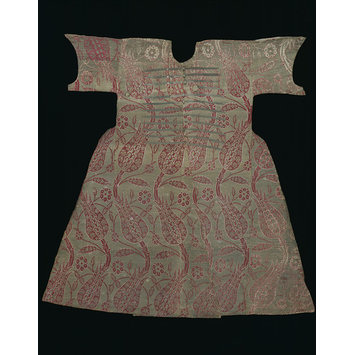

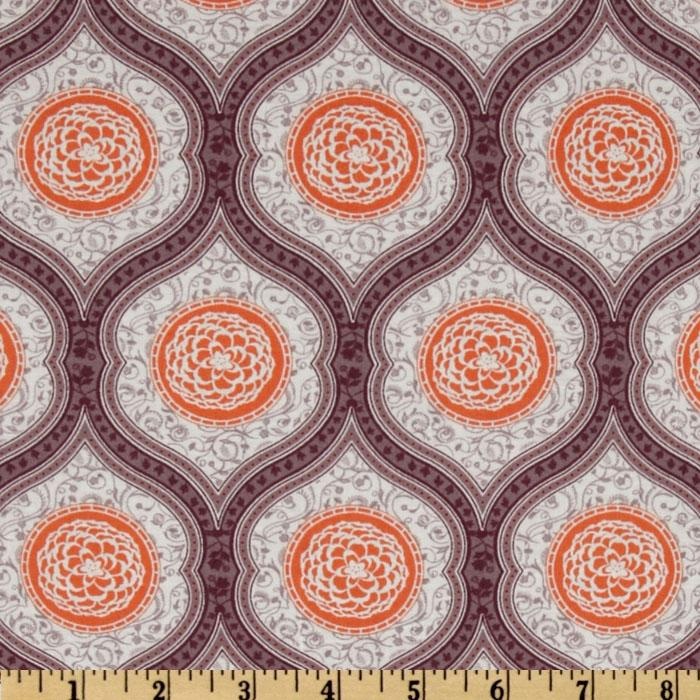

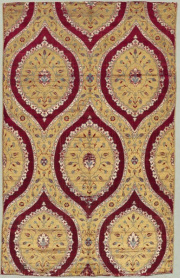

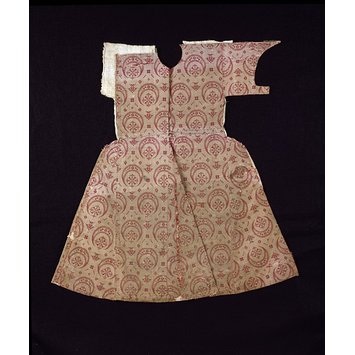

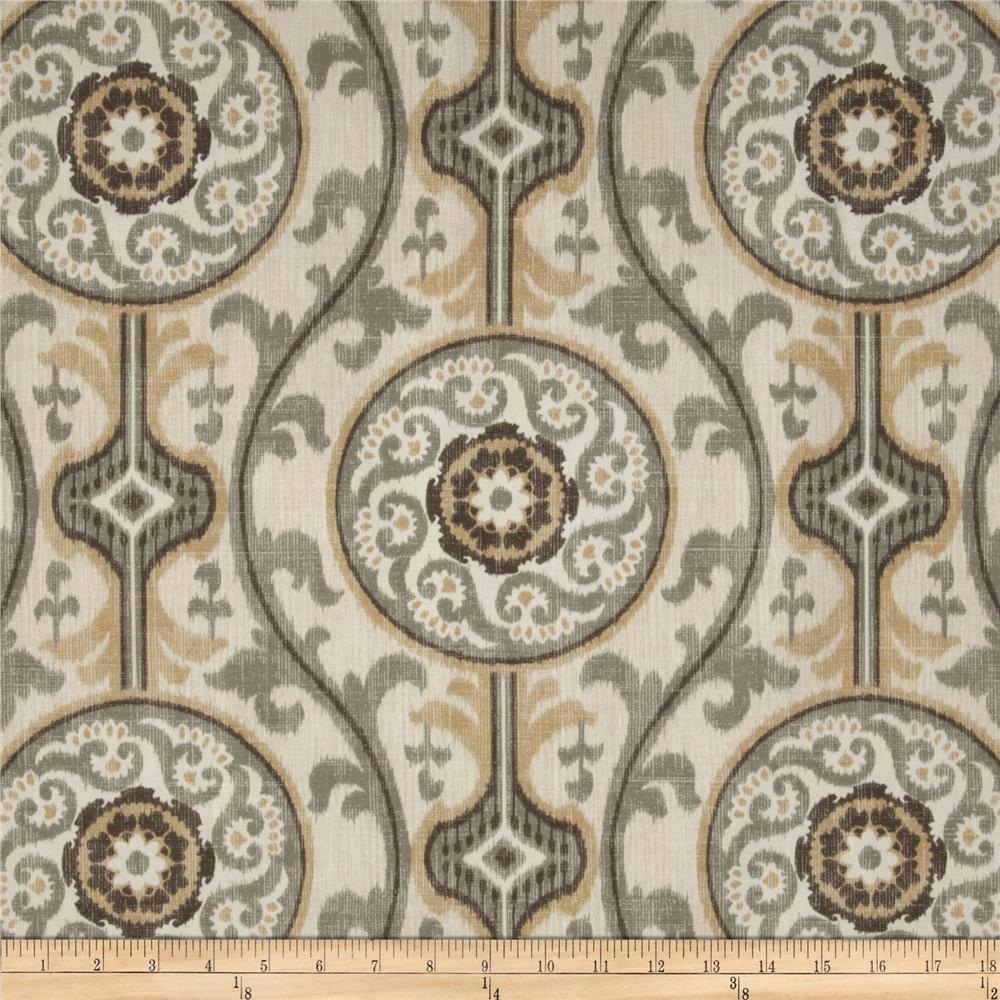

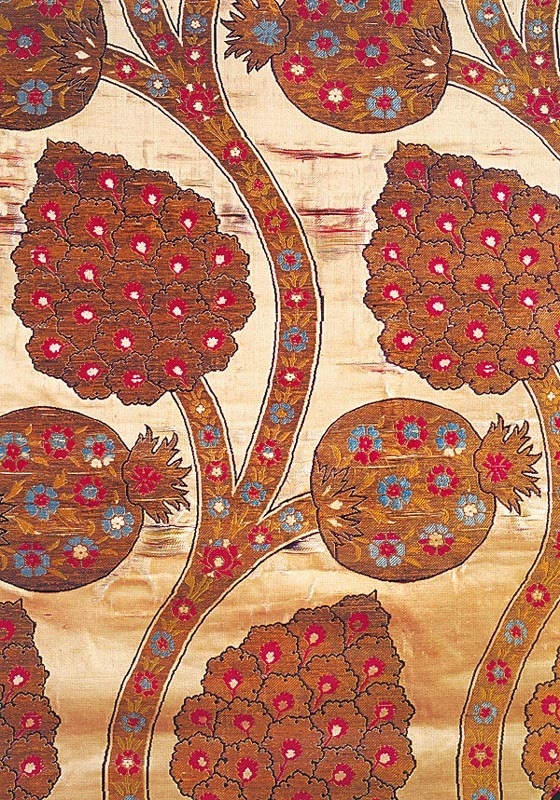

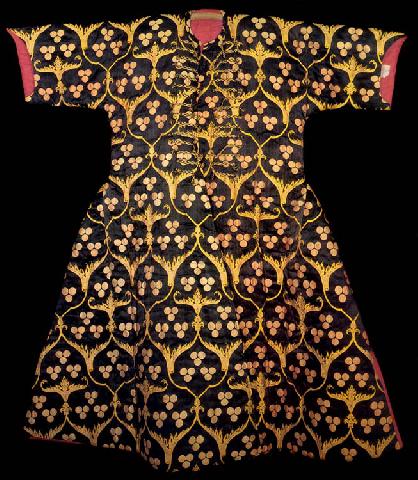

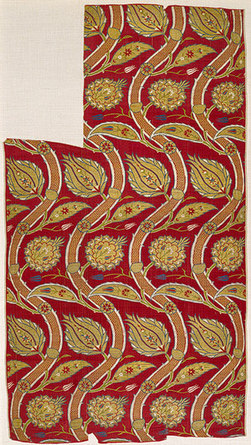

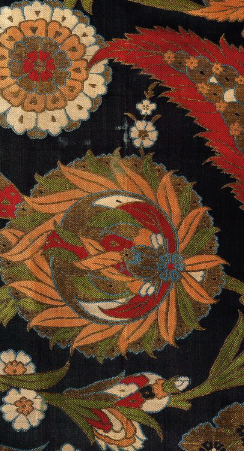

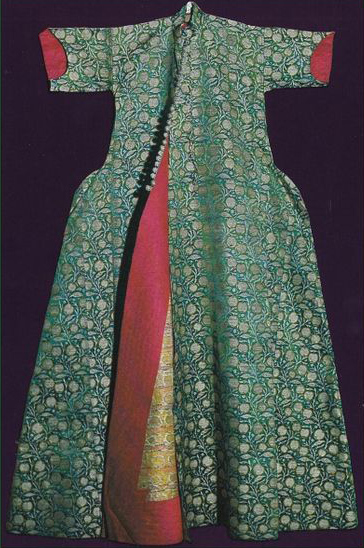

Gilding  Photo credit: Lady Behiye bint Kismet Photo credit: Lady Behiye bint Kismet Another option that was used in our time period is gilding of fabric. Lady Behiye bint Kismet is working out the process to lay silver onto fabric to reproduce a period caftan that is attributed to a daughter of Murad III. I understand the garment will be finished this winter and I quite look forward to seeing the results. You can follow her progress on her blog here: http://behiyebintkismet.wordpress.com/2013/08/27/silver-gilding-on-silk-gilding/ Appliqué and Debossing There are two other techniques that I have seen in period examples that I hope to see eventually done in the SCA. Too many projects at once and too much work has been needed on my car, so little progress has been made! I did, however, finally cut out my Ottoman coat for 12th Night. Some of the fabrics I may be using are below. The Rust colored fabric with the repeating medallion motif is one I have had from sometime and it will become the Entari. The golden fabric is linen that shall be the coat lining and the green is silk for the facing. The large pomegranate pattern on the left will possibly be a set of sleeves or hat or even the lower part of a pair of salwar (pants). The lovely large scale pattern on the right will become shoes and possibly a hat. I also have blue linen on which I will stencil a pattern for my chirka.  I also found that one of the oak trees near the cabin is infested with oak galls. I have been collecting these for a few weeks now (I now have 3 or 4 times as many as I have in this picture) and will be crushing them to test some dying out with them. I hope to have enough galls to run small samples of both wool and linen using two different mordants (alum and iron). I look forward to seeing how the samples turn out!  When I was looking through the inventories of several online shops for my posts about Ottoman fabrics, I found the quilting cotton to the left. I initially liked liked - the motifs are of an appropriate shape and organized in a period fashion. The red is nice (it also comes in kiwi which also works) and the rest of the color palette is not perfect in my mind, but not horribly bad either. The scale is not as large as I would love to see, but each motif is 4x2 inches which is really not bad for a quilting fabric. I ended up rejecting this fabric, however, because of the way the color was used - with a series of four colors being used separately on the motifs. I saw something only few days later that made me change my mind. Below is a caftan belonging to Osman II (1618-1622, so just out of the SCA range). The motif itself is very different, but the arrangement is the same. The color palette is actually quite similar to the one in the cotton I found, and has red, pink, gold and blue as does mine (and an additional olive shade as well). But what is most interesting to me, is that the color arrangement in each motif is different, much like the quilting fabric.  I also found one more jewel. This is a detail from "The Disputation of St. Catherine," by Pinturicchio and was completed around 1495. (Gentile Bellini's work as an artist who traveled in the East is credited as being the inspiration for the images of Ottoman men that sometimes appear in Renaissance paintings, including this one.)  So, the lesson I have learned is not to instantly reject something without looking a bit deeper. And, of course, I am now somewhat tempted to order this one on the kiwi background.... ;-)  Late 16th Century Ottoman Caftan. Late 16th Century Ottoman Caftan. Perhaps one of the most appealing things about Ottoman costume is the amazing patterning of these grand silks. Unfortunately for the reenactor, finding similar patterns in an affordable form is not an easy task. Below I will illustrate a few of the more common types of patterns and will include examples of extant textiles that follow that form. After that, I will discuss some motifs that you see on period textiles and finally, I will provide links for fabrics that I would consider purchasing for garb and why I think they would make more than decent choices (of course, some of them are inaccessible due to cost, but they are too lovely not to share). Arrangement Staggered designs are also enclosed with a lattice style frame. (The fabric with the blue background is late 16th century and is from the V&A museum. That with the red is from the first half of the 16th century and is from the Cleveland Museum of Art.)

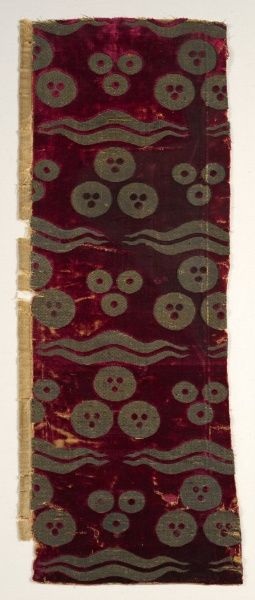

Common Motifs Ottoman weavers and artisans use both nature inspired designs and those with a more solid, geometric form. Below are some samples of designs used by the Ottoman court.

Patterns of wavy lines, which are sometimes referred to as tiger stripes also appear in both art and textile. Designs from nature include, among other things, tulips, pinecones, pomegranates, fruit, and leaves. The Matter of Scale If you look at most of the examples I posted above, you will see that the prints tend to be large scale compared to the garments. Giant flowers, circles and vines can often be found on home decorating fabrics (think of woven textiles meant to clothe sofas) but not so often in the apparel lines or in quilt fabrics. Sometimes we find a near-perfect print in terms of style, but each motif is a mere inch across and there is not enough ground visible behind them. Would I buy personally buy that tiny print? It depends, if the motif itself is appropriate, and the layout is nice and the colors period, most definitely, even if the scale is small. (Some small-scale designs could actually pass as Persian imports, so one does not have to avoid them completely!) I look for bold, striking patterns and purchase them when I can, but given the modern tastes in textiles, I do not encounter these things as often as I would like so I will choose something that at least has a few correct elements or I will opt for a solid. So where does all of this leave us? I have done some pretty extensive scouting online in search of period Ottoman patterns for use as modern reenactors. There are several (nice) options for unlimited budgets, but few that perfectly fit our needs. That being said, if you look hard enough you can find some gems or some very lovely fabrics that make reasonable substitutions. Below are some of my choices along with extant samples that defend those picks (in my mind, at least).

And finally, here is a wonderful collection of fabrics that are extravagantly priced but are wonderful to dream about. http://www.soane.co.uk/product/fabrics/turkish-blossom#

This one is probably my favorite of all of them. Sigh... http://stores.kasaboo.com/-strse-5956/anichini%2C-goredean%2C-lucrezia%2Csheeting/Detail.bok And look at the others by this maker (you will NOT regret it): http://www.anichinifabrics.com/index.php/catalog/product/view/id/293/s/hazeran/category/7/ http://www.anichinifabrics.com/index.php/catalog/product/view/id/289/s/anja/category/7/ One More Option

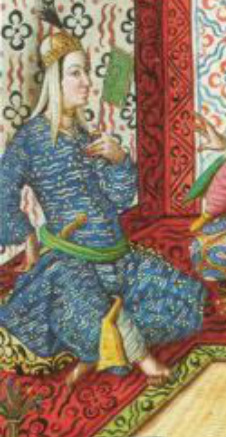

You can always attempt to paint, stencil, emboss or otherwise decorate your own fabrics to imitate these glorious designs. I have seen people stamp designs on silk, apply silver leaf to fabric, stencil large scale motifs onto cotton or linen and I am even going to attempt to machine embroider a cintamani design on linen fabric to create an allover pattern. Be creative and experiment!  This masterwork of silk does not repeat the pattern in the entire garment. This masterwork of silk does not repeat the pattern in the entire garment. There was no lack of color in the attire of the Ottoman nobility. The range of dyes they could produce covered the spectrum, as is shown in both extant textiles and in paintings of the time period. Commonly used plant dyes (with mordants of alum, iron, tin, or copper) were indigo for blues; madder for reds and oranges on wool; weld, safflower, larkspur and saffron were used for oranges and yellows; certain types of buckthorn berries gave green; and brazilwood gave purplish red. Insect based dyes such as kermes, lac, and Mexican cochineal produced the most vibrant and valuable reds and crimsons. Additional colors were produced by overdyeing one color with another. A yellow dye over indigo gave greens, indigo and henna produced blacks and indigo with a crimson dye produced deep purples.*  Late 16th Cent Ottoman Painting. (Photo credit British Museum) Late 16th Cent Ottoman Painting. (Photo credit British Museum) Miniature paintings also show a variety of colors being employed by the residents of the Ottoman Empire. Blues, reds, oranges, greens and yellows appear on people from varying walks of life. Based on paintings, we can also determine that colors appear to have been used liberally, with little modern sense of "matching" (likewise with patterns). Some personal things that I keep in mind when making color choices for an Ottoman persona:

For a selection of both extant textiles and extant art, please visit my Pinterest page to see further examples of the amazing range of colors used for Ottoman silks. http://pinterest.com/alfrunketta/ottoman-and-middle-eastern-costume/ * Dye information came from two sources: Topkapi Saray Museum: Costumes, Embroideries and Other Textiles and Ipek: The Crescent & the Rose: Imperial Ottoman Silks and Velvets.

Ottoman textiles, particularly those used by the ruling class, were sumptuous. Elaborate or bold brocades in silk, often with metal threads, were coveted. The color palette was rich and there was a variety of textures from satins and velvets that added to the richness of these fabrics. Unfortunately, this splendor is not often replicated in patterned textiles that are affordable to us as reenactors. It is rare to find a truly period Ottoman print, and even more rare to find that in a form that is either affordable or comfortable (i.e. a natural fiber). To better recreate the extant garments (which one must also remember were often imperial property and were ceremonially worn by the sultan or were given by him as gifts), we have to do our best to wade through the maze of lovely (but often overly busy) quilting cottons or suffer through the potential heatstroke that can come from wearing fabric that is better suited to a sofa. When I am, however, looking to find that elusive perfect fabric for new garb, I tend to take into account four things: Fiber, Color, Pattern & Scale. (And there is another category as well, UWYH. That stands for "Use What You Have". If you have something semi-suitable in your stash and are questioning buying more, or are just starting a new costume endevour, it never hurts to do a bit of stash-busting first while learning to make a new type of garb and then try to find that perfect fabric.) Below and in several posts yet-to-come, I will discuss my own personal preferences and methods for selecting fabrics for my Ottoman garb and how I deal with the real world issues of money and inaccessible reproduction textiles. Fiber Fiber content is a key factor in the decision making process of many SCAdians. Most reenactors prefer garments that will be cool in hot weather and that will breathe well (something one will not get with polyester or acrylic fibers). Silk was most often used for the imperial caftans, but there is at least one extant garment in wool that I have seen (and I would guess there are others). Linings were often linen or cotton or silk. I personally often resort to plain linen for my SCA garments, even if that would not have been the preferred choice for that garment historically. Why? Because I know that I will get the most use out of garb that is comfortable to wear at summer events, particularly Pennsic. I also think that sometimes the solid colored garments are under-represented among Ottoman and Middle Eastern reenactors in the SCA (many miniatures show people in solid colored garments, and even some of the imperial garments are in a single color of silk). However, if I find the "right" design, I will often purchase a synthetic fabric and use it to make my entari. The entari is a long coat, often worn over a shorter inner coat - the chirka, which in turn is worn over a gomlek (a sort of chemise). I know that if the outer coat becomes too uncomfortably hot, that I can remove it and still have my chirka and gomlek on. I am also more likely to use a synthetic for an event like 12th Night, which is in the winter, than I am to use it for a potentially humid event such as Pennsic. Some people are less bothered by wearing synthetics than others so decisions about fiber content should always be based on personal comfort preference. Silk was used in period by the Ottoman Turks, as was cotton, linen and wool. Additionally, Indian block printed cottons were imported at the time as a luxury (but I would not use these for a coat). Silks were made in the empires silk centers, but were also imported from Italy and elsewhere in Europe. My choices in fiber - for solid colors - can be found below (in no particular order). (Note, these are my preferences for the things I often use myself or that I recommend to people who are looking to purchase fabric for new Ottoman garb.  Linen As I have said many times, I love linen. I particularly love to use this fabric in the 3.5oz weight (handkerchief weight) for my gomleks and undergarments. I also make my salwar out of this for Pennsic as it is very cool and comfortable and gives a nice drape at the ankles. I prefer the mid-weight (5.3 oz-6oz) for my coats. Do I think that linen is the absolute best choice for an Ottoman coat? No, but I do think it is more versatile for the average SCAdian. Linen also comes in a wonderful range of colors, many are period for Ottoman clothing. It also makes for a nice lining inside a coat made from a synthetic or silk fabric. My favorite sources are: http://www.fabrics-store.com/ http://www.graylinelinen.com/  Cotton Cotton is perhaps the most affordable option for garb, and the easiest to find at your local fabric or quilt shop. It comes in broad range of colors and is even easy to dye yourself. It also comes in a plethora of prints (more on prints later). Light weight cottons make wonderful gomleks and undergarments and even salwar. A quilting weight cotton can even make a nice coat (but I prefer to line the garment to add body and stability, especially if one is aiming for the snug-in-the-torso look). Occasionally one can even find a heavier weight printed cotton in the home decor section or a cotton twill in the apparel section that can make for a wonderful coat fabric. One choice that I love if someone is looking for a cotton is a cotton sateen. I will note here today that often people categorize and cotton fabric with a sheen as sateen, and any other fiber with that same sheen as a satin. The difference in satin and sateen is actually in the weave structure, not the fiber content. (If you care to see diagrams of the difference, check out the diagrams here: http://stgeneve.com/quality_defines/covering/weave_types.htm ) A cotton sateen is affordable and has a nice luster (though not as rich as silk) and is not a bad option for a comfortable fabric for recreating Ottoman garb. Resources for cotton sateen (one can also search online for fabric stores carrying this fabric, there should be quite a few and those carried by home decorating stores might have heavier sateens that will work even better for coats): http://www.joann.com/sateen-solids/prd12710/ http://www.hancockfabrics.com/Cotton-Sateen_stcVVcatId539047VVviewcat.htm Another fabric with a satin finish that is a cotton-silk blend that might be nice for garb (I personally have not used this one yet) is the cotton-silk poplin from Fabric.com: https://www.fabric.com/buy/bz-148/radiance-cotton-silk-poplin-cranberry Another cotton option that has a luxury look, but is both comfortable and washable, is Cotton Velveteen. Velvet is period, and cotton velveteen, while not perfect, is a fair substitute for the rich silk velvets of the Ottoman empire. Resources for cotton velveteen: https://www.fabric.com/apparel-fashion-fabric-velvet-fabric-velveteen-velour-fabric-doux-cotton-velvet-fabric.aspx http://www.joann.com/empire-velveteen-fabric/xprd728531/ If you are looking for sheer cottons to use for a gomlek, check out cotton voile. This fabric is light, airy and can produce the sheer look that shows up in many of the Ottoman miniatures (see image of palace women from I Turchi; Codex Vindobonensis 8626 below). Cotton is an appropriate material for these garments. https://www.fabric.com/buy/dj-385/cotton-voile-supreme-wide-white One additional word about cotton, if you are looking for comfort avoid cotton/poly blends. Even if the fabric is light in weight, you will be doing yourself no favors by wearing it.  Quilted silk Caftan. Quilted silk Caftan. Silk Silk is still the ultimate luxury fabric (and often still carries a luxury price). Occasionally we can get silks that fall within our price range and occasionally those are even a good choice for reproducing period garb. Silks were made in the empires silk centers, but were also imported from Italy and elsewhere in Europe. Real silk, however, is very pricey and I find it just as uncomfortable in humid weather as I do synthetics. The less costly silks are not always great for our recreations. Silk Noil (often called Raw Silk) was not used in period and has a very different look and texture than historic silks. When I occasionally still find some of this in my stash, and tend to use it in place wool for tunics and other early period European garments and look for something with more luster for my Ottoman clothing. One often affordable silk is called China silk or habotai. This is a very light weight, plain weave silk that can work for a gomlek, veil or even very light weight pants. I would avoid using this fabric for a coat as it does not have the necessary body to recreate an Ottoman look, but it makes a nice lining fabric. A resource I have used for Habotai is: http://www.thaisilks.com/  A silk "brocade" I bought on Etsy A silk "brocade" I bought on Etsy One other item I often look for in silk are the Indian "brocades" you can find on Etsy and Ebay. They are typically sold as fat quarters for quilters but can often be bought by the yard as well. They are actually jaquards rather than brocades, but occasionally they have patterns that work for Ottoman costuming (and more often than that you can find patterns suitable for Persian garments).  Another option in pure silk that can be affordable (especially if you monitor sales and clearances), is dupioni silk. This is a somewhat controversial textile in the SCA because it has a slubby texture that would not have been found in period. I personally will not hesitate to use it if I wanted the luster of real silk, nice body/drape, and a wide range of period colors for a project and could not find or afford a better fabric. (And again, this is an opportunity for education! When someone comments on your dupioni garb or if you use the item as an A&S entry you can explain why you made the choice and describe what a more period silk would look like.) Resources for dupioni: https://www.fabric.com/apparel-fashion-fabric-silk-fabric-dupioni-silk-fabric.aspx?Source=SubCategoryLink http://www.thaisilks.com/ http://www.fabricmartfabrics.com/Dupioni/ For a coat weight solid silk I would recommend (if you have the $ to spend) looking for silk satin, taffeta or velvet. Silk satins and taffeta can often be found in high end fabric stores among the bridal and special occasion fabrics. Velvet can also be found there of in the home decor section. Often one can find silk velvets that are a blend of rayon and silk (Thai Silks, mentioned above carries this textile) and you can also find attractive satin, taffeta and velvet as synthetics. (If you are looking for a more period satin that is synthetic, look to the better bridal satins rather than those destined to become Halloween costumes, the luster and weight of the two are quite different). Another option that can occasionally be found is silk twill. You have to scout around for it, and get swatches to verify that it is really silk and that it is heaver than lining weight fabric. Resource for silk tafetta/twill (this site typically has a small selection of 100% silk tafettas and occasionally silk twill): http://www.fabricmartfabrics.com/Taffeta/ Another type of tafetta that was available had a watermark pattern - often called moire. Silk moires are not easy to come by at this time, but synthetics with this distinct patterning can still be found in the home decorator or special occasion apparel departments of many fabric stores.  An unbelievably expensive, but amazingly period, fabric made from Viscose. An unbelievably expensive, but amazingly period, fabric made from Viscose. Synthetics (yes, I used the "S word") Unfortunately, many of the best period patterns are offered only in synthetic fabrics and we have to make a choice to suffer in the man-made fabrics or opt for something else. Some fabrics are confusion to those new to the textile world. Rayon and Viscose are made from cellulose rather than chemical compounds and can often be comfortable to wear. Polyester tends to wash well and last awhile, but does not breath at all and can melt if it gets too close to fire. Acetate is often used for synthetic tafetta, but can discolor if something is spilled on it and is terrible for changing color with sweat stains. If you do not mind a synthetic, and come across and find something that looks real, I would never suggest that you not use it. More to come soon concerning Color and Pattern & Scale! |

About Me

I am mother to a billion cats and am on journey to recreate the past via costume, textiles, culture and food. A Wandering Elf participates in the Amazon Associates program and a small commission is earned on qualifying purchases.

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

Blogroll of SCA & Costume Bloggers

Below is a collection of some of my favorite places online to look for SCA and historic costuming information.

More Amie Sparrow - 16th Century German Costuming Gianetta Veronese - SCA and Costuming Blog Grazia Morgano - 16th Century A&S Mistress Sahra -Dress From Medieval Turku Hibernaatiopesäke Loose Threads: Cathy's Costume Blog Mistress Mathilde Bourrette - By My Measure: 14th and 15th Century Costuming More than Cod: Exploring Medieval Norway |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed