Note, if you belong to a reenactment group that has specific standards or a guide book, one should always consult that book or the authenticity officers as to what is allowed. If you do not care about historical accuracy and just want what you personally feel is a “Viking look”, that is fine, especially for the SCA or Viking or Ren Faires. This article is not geared to telling someone what they are doing is “wrong”, but rather to help align the evidence and help those who might want to take the next steps towards a more realistic historic interpretation.

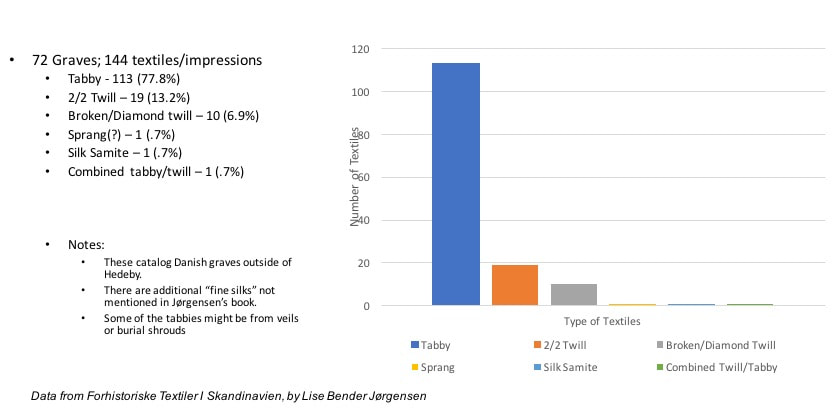

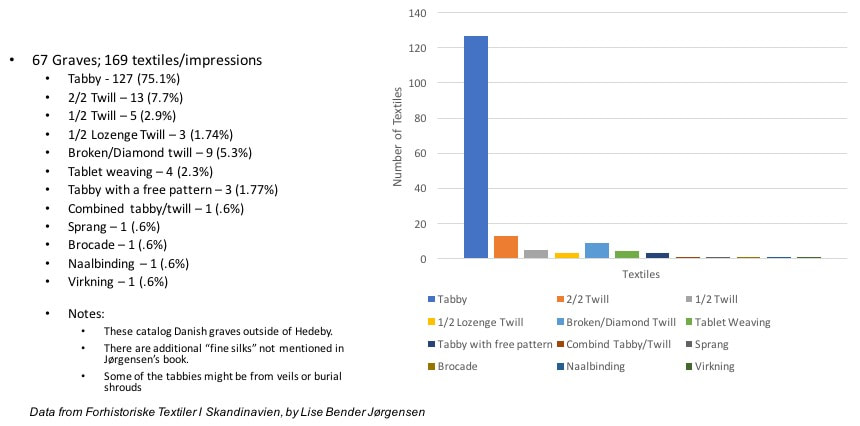

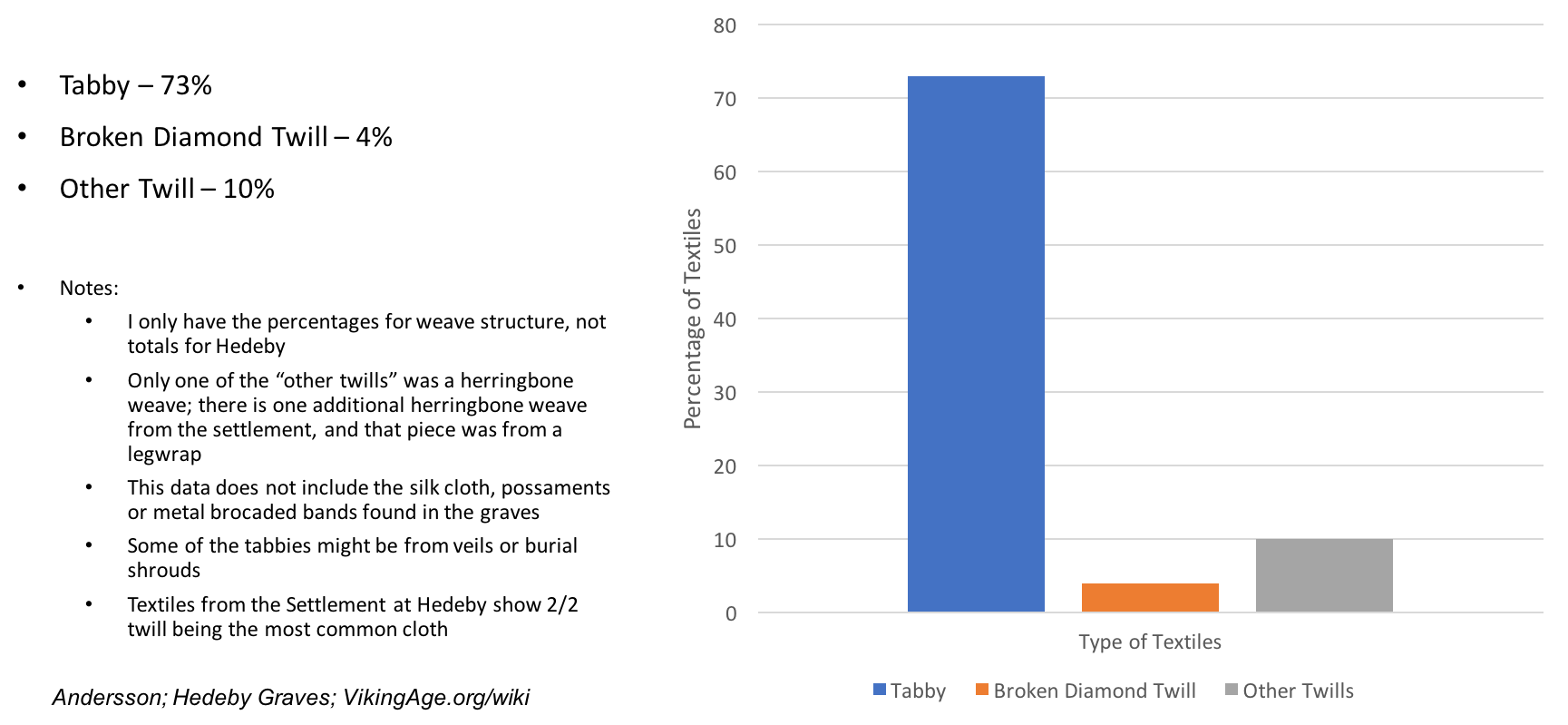

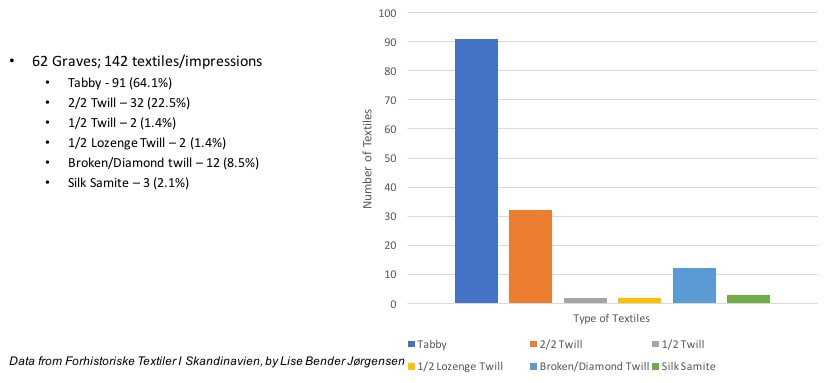

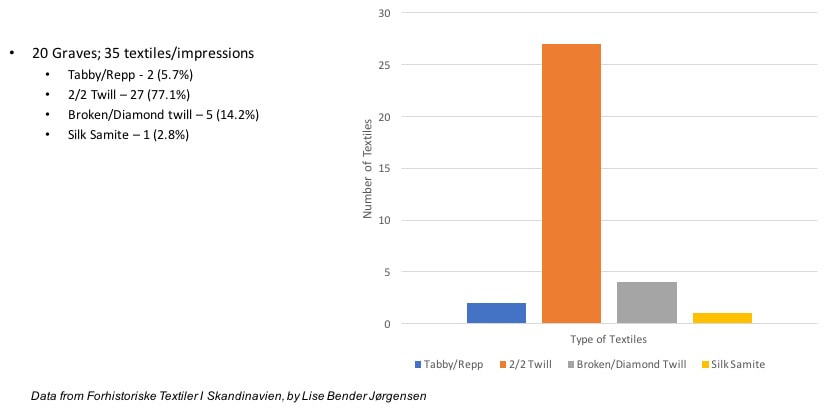

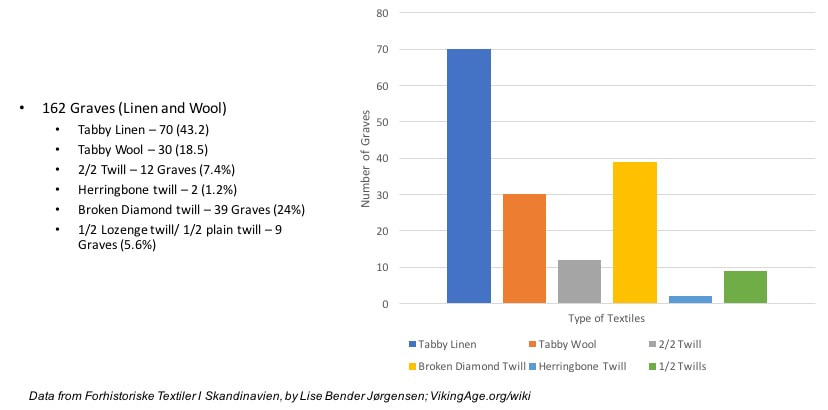

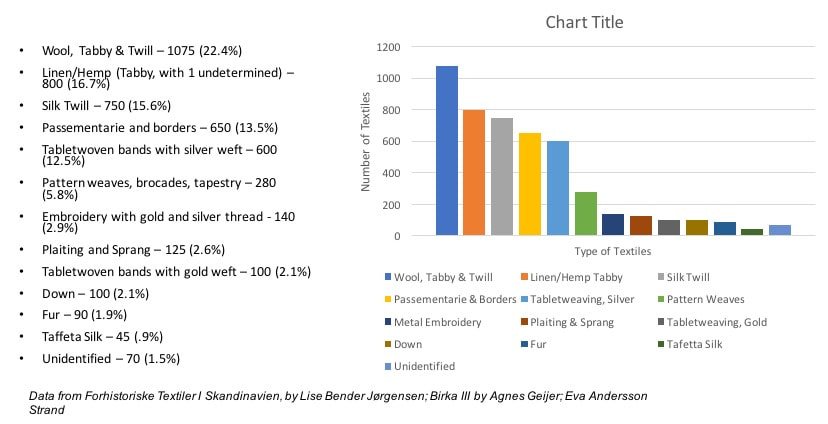

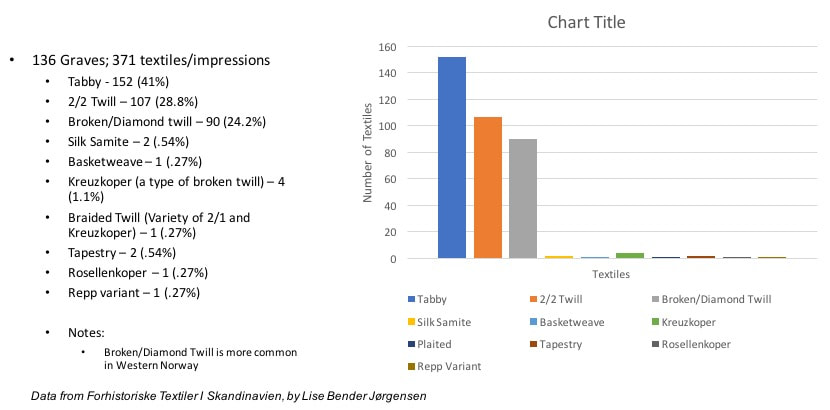

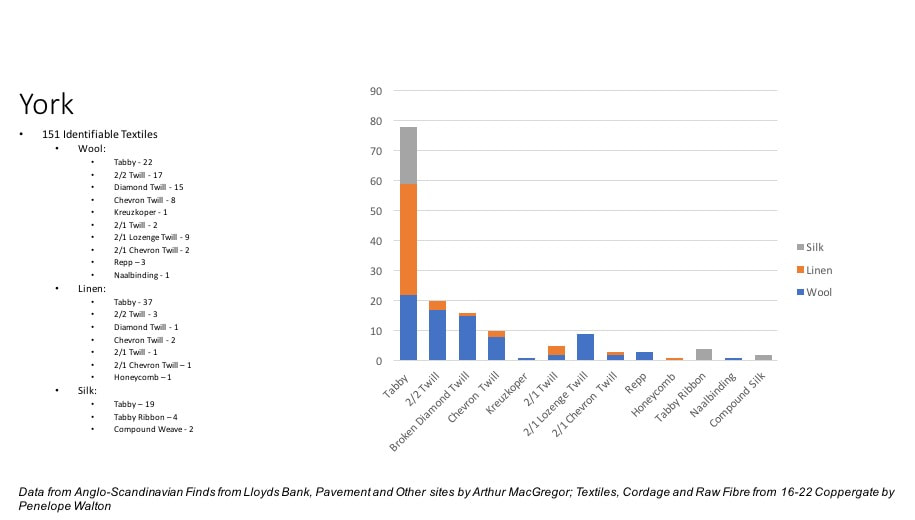

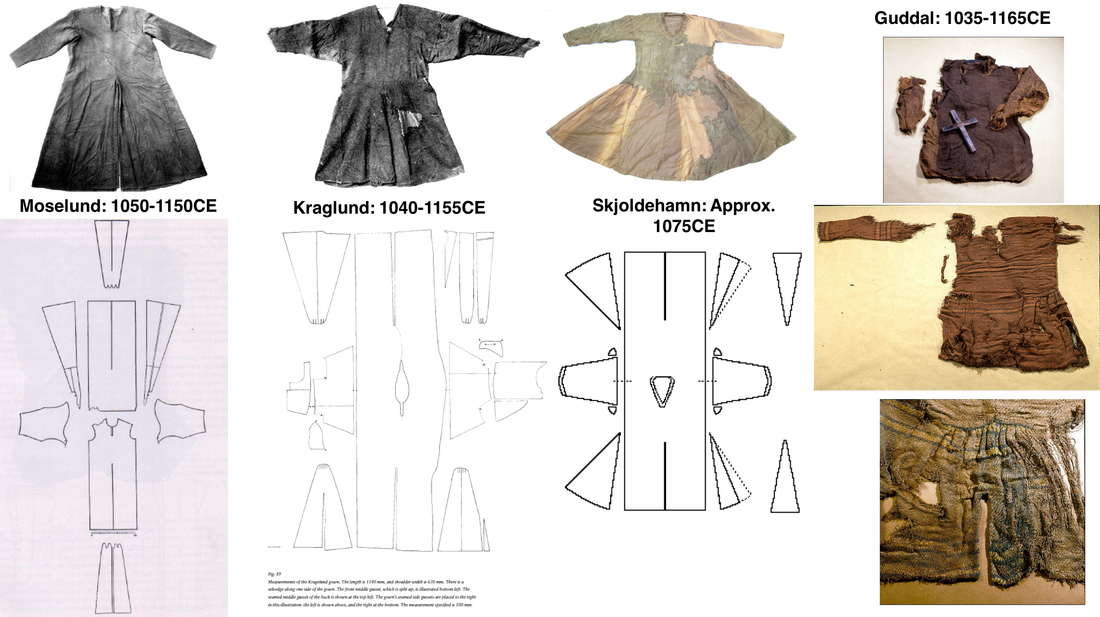

- 1)Textiles – the most common textiles in the Viking Age are wool and linen. The most common weaves are tabby (plain weave, also called linen weave or canvas weave) or twill (this is a diagonal weave structure such as you find in your blue jeans). My charts HERE show how common different weaves were in different areas. Researcher David Stříbrný also has an article HERE about how uncommon herringbone twill is in period as well. I have another article HERE which will help you distinguish a period diamond twill from types that we do not often see in the Viking Age. Plain tabby and twill in solid colors are the best choices for most situations.

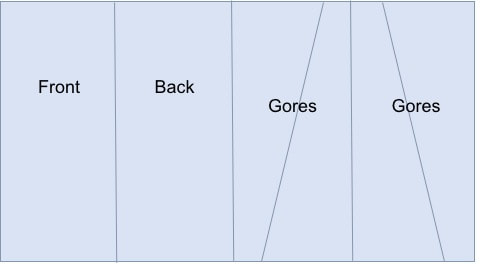

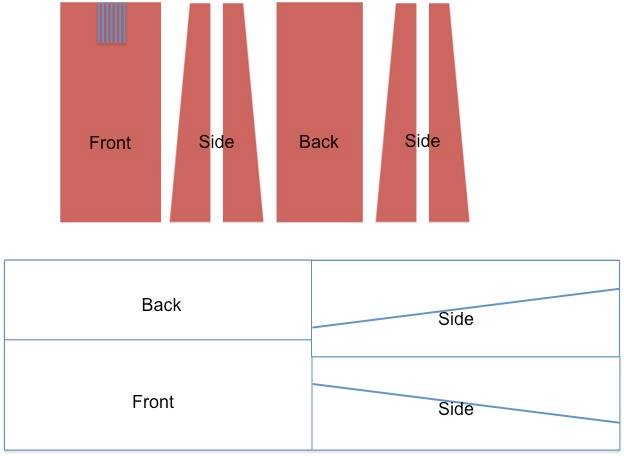

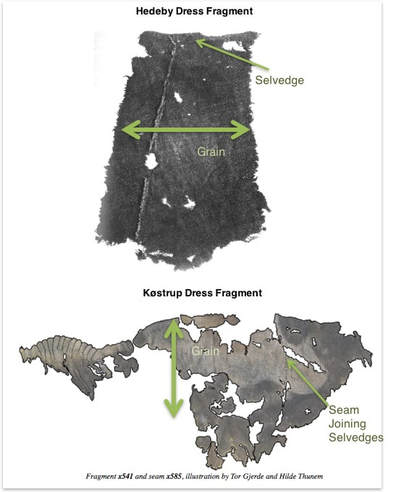

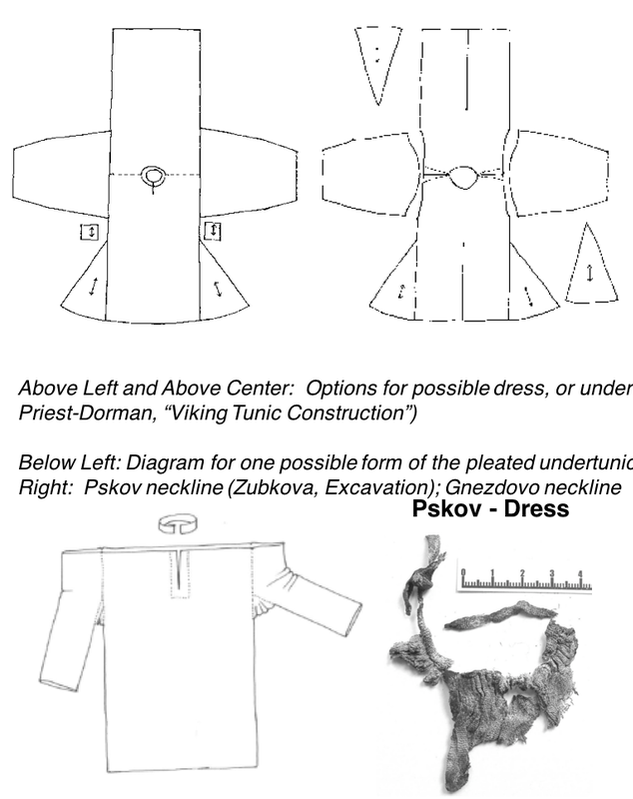

- Not every Norse woman in the Viking Age wore an apron-dress (or those that did might not have worn it in all situations). I have an article on apron-dresses HERE and Hilde Thunem talks dress/tunic/gown construction HERE. This is fantastic, because brooches are often the most expensive part of a woman’s kit, and starting with a simple dress means you can sort out what details of your persona BEFORE buying that pricey bling.

- While it is common to see sprawling herringbone stitch on the outside of seams in reenactment, this practice is not supported by evidence (nor is it actually practical, as the constant loops of the stitch can sometimes twist seams). This practice comes from a misinterpretation of evidence from Mammen and I discuss it HERE and HERE.

- Since herringbone stitch is out, how do you embellish a garment? I have ideas in a two part series of articles that start HERE. The article covers braids, cords, and trim made of silk fabric.

- Another option for decoration is tablet weaving, but keep in mind that period tablet weave tends to be very narrow and made of fine yarn. We see more complex methods, such as brocading, than we do simple turn-based patterns. If you plan to weave something, and are looking for accuracy, it is good to verify that the pattern you are working from is from the current state of research. Many brocade patterns have been revamped into turn-based patterns and the effect is so vastly different that it really is not the same thing at all. Silvia Asiling has a fantastic example of this on her site HERE.

- Remember that you need not add decoration at all!!! The quality of your textiles is often a better indicator of the status of your persona. Add some jewelry or other accessories (time/place/status specific) and you can be of the highest status without the need to clutter your silhouette with “Viking-esque” popular cultural items.

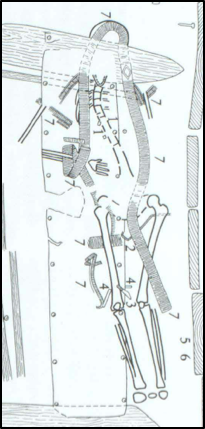

- Leather accessories – While we commonly associate belts and belt pouches with everyone in medieval or early medieval period, it would be good to look into whether this is actually something your persona would have had. In many cases, women might not have work belts at all, and for men there is a tendency to go overly large and overly long with both belts and pouches (often, large belt buckles are for horse harness). There is some great research on men’s belts HERE.

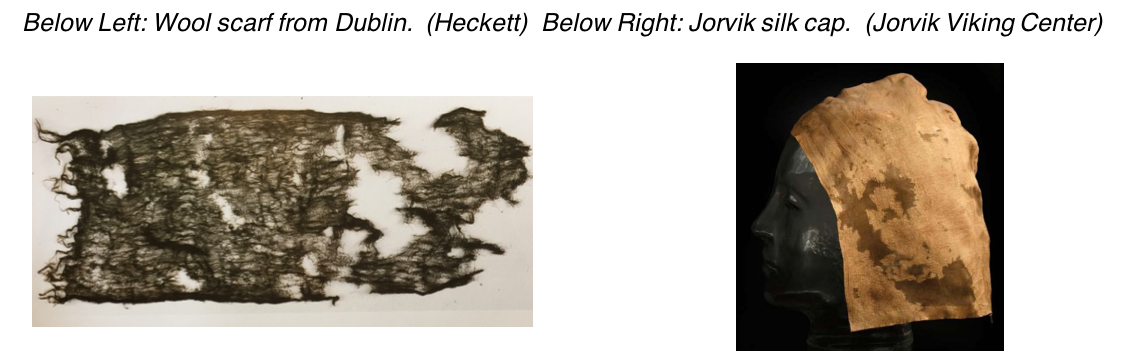

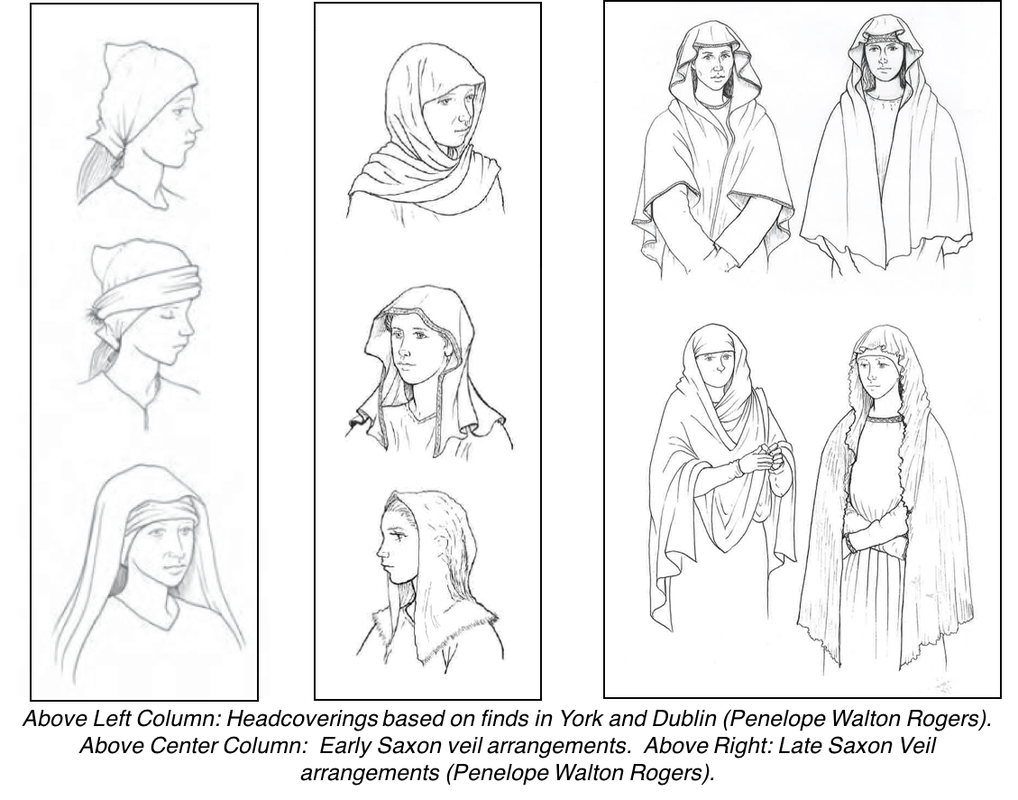

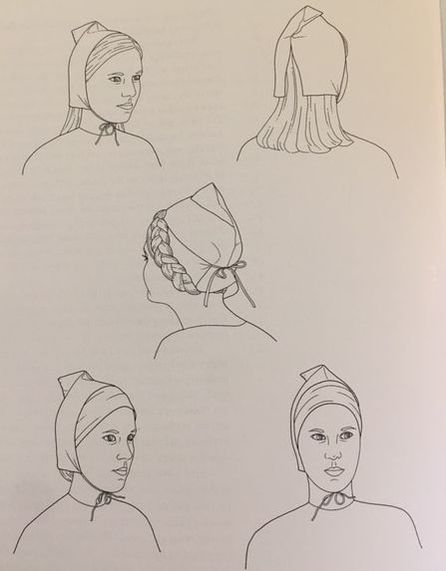

- Proper headwear can make or break an outfit. It is good to invest some research time into this before deciding what is proper for your persona. There are reenactor myths that Christian Viking women covered their hair with a veil and that Pagans never did, and that statement is not supported by evidence. A veil can be an item of fashion and practicality as well as an element of faith. At times, it is possible that women chose to cover their hair for practical reasons (such as keeping smoke out of your hair or the sun from baking your head), and not cover it at others.

- Heavy swags of beads with multiple strands or bead spreaders are exceedingly uncommon in the general Viking period. Some graves that are wealthy enough for oval brooches have no beads at all. At Birka, we see an average of 22.7 beads in graves (and many of those are small), and at Hedeby, the average is only 8.3 beads. You need not break the bank to buy piles of beads to follow popular modern conceptions of what looks “Viking”. Starting with a few handmade beads and working up a collection of accurate types is very appropriate. Some of my bead research can be found HERE.

- Heavy make-up (Heilung style), use of leather and leather armor (especially as “clothing”), knee-high boots, and ragged pelts slung over the shoulders or worn as cloaks are items of fantasy. If your goal is accuracy, I would step away from these items and work towards grounding your kit in the evidence.

I have a number of articles here on my blog that can help sort additional items out. They can be found the topics of Viking Costume: Beyond the Myth and Viking Textiles – Looking Deeper. For excellent articles on costume I recommend Hilde Thunem and Susanna Broome. For fantastic research on armor, weapons, leather goods, and more, I highly suggest David Stříbrný’s site.

Given that most of us do not launch right into high-end historic reenactment, we can take our time, start simple, and thoughtfully develop the details of our persona (time, culture, location, status, wealth, occupation, and circumstance) and build out from there, making upgrades or adding finer details as we go.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed