In my Textiles and Dress Class, I discuss what types of cloth are the most common in the Viking Age and talk bit about tracking down modern textiles that, even if not perfect, are good options for reenactment. Another item I touch on in that class is making good choices. We all love the rare graves, and unique items, but one kit made of 20 different unique pieces steps away from being a good historic representation of a time. An easy way to start building a better kit is in your cloth choices, and one can consider weave structure, threadcount, and color when making those choices.

For me personally, I lean towards the most common weaves (tabby and twill), whenever possible. I will add an element such as broken diamond twill to my kit for a very high status persona, but would not add broken diamond twill, herringbone cloth, a silk band, tablet weaving, and possements all to one costume because it would be showing too much that was rare in period all at once. My love-hate relationship with herringbone reflects the fact that I find the weave attracted, but I am often frustrated when it tends to be more readily available in the weights I want than the more historically common twill and tabby. (And this is additionally frustrating when the herringbone cloth is two tone, which is also something less common in period.)

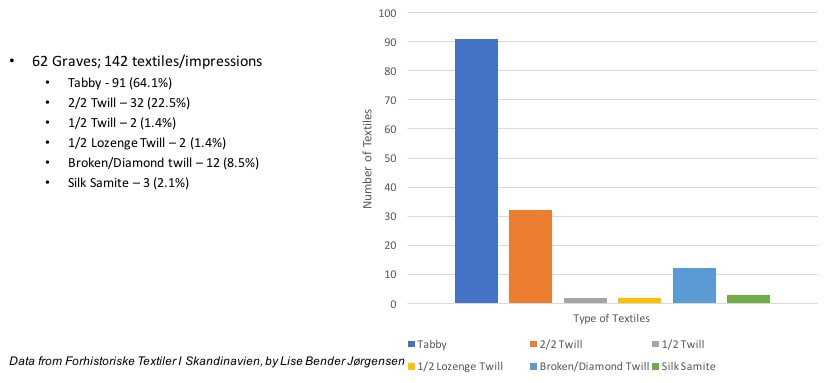

I turned the data from Lise Bender Jørgense's book Prehistoric Scandinavian Textiles, as well as some additional works, into charts to help illustrate how common (or not) weaves were in various areas.

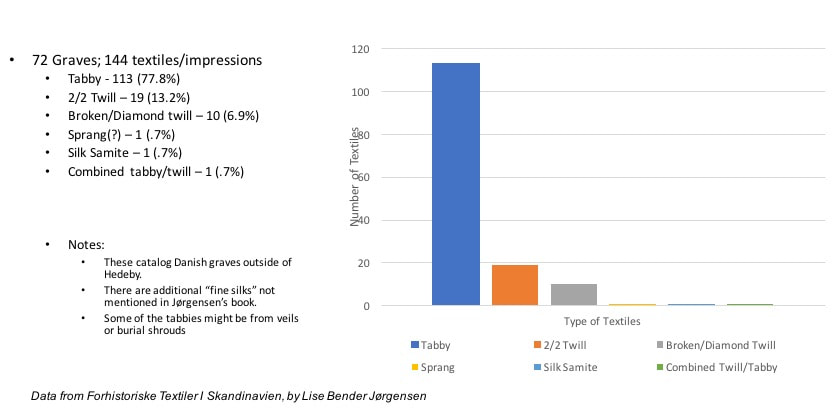

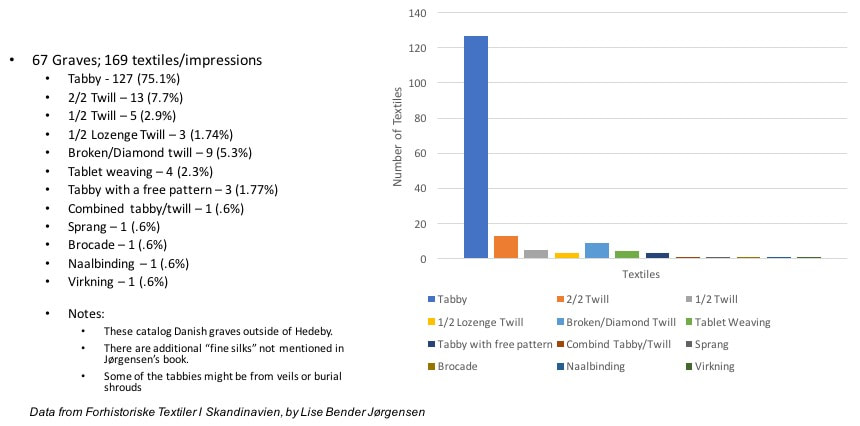

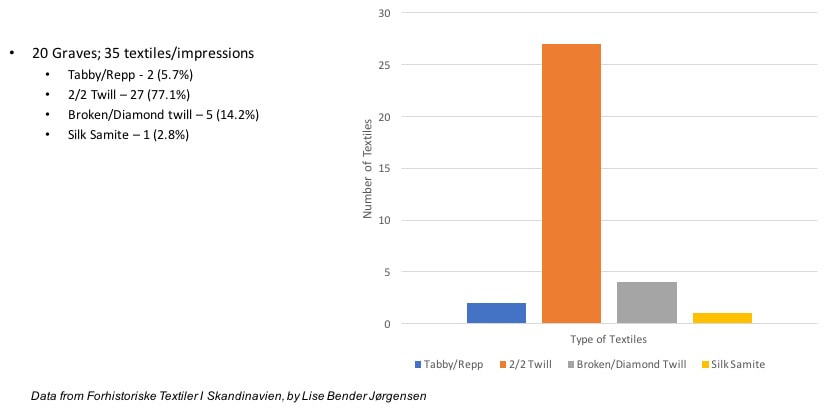

Denmark - 9th Century

Jørgensen's work on the textiles of Denmark covers graves, excluding Hedeby, and is nicely broken down into two centuries. One issue with this work that it only covers weave structure in the synopsis, and for me to break it down between linen and wool, I would have to reference back to collect that data. Further, some of the data here is provided by textile pseudomorphs, which only show us the weave structure and leave no cloth to analyze. It is likely that some amount (even a good amount, according to the author) of the tabby shown here is linen. It is also possible that some of the tabby weave represents a type of fine, open weave wool that was used for veils and mantles but that was also used as specific burial clothes or covers. It is also noted by the author that there are additional "fine silks" not covered in her work because they were detailed elsewhere.

For Denmark the charts are based on the total number of textiles/textile impressions.

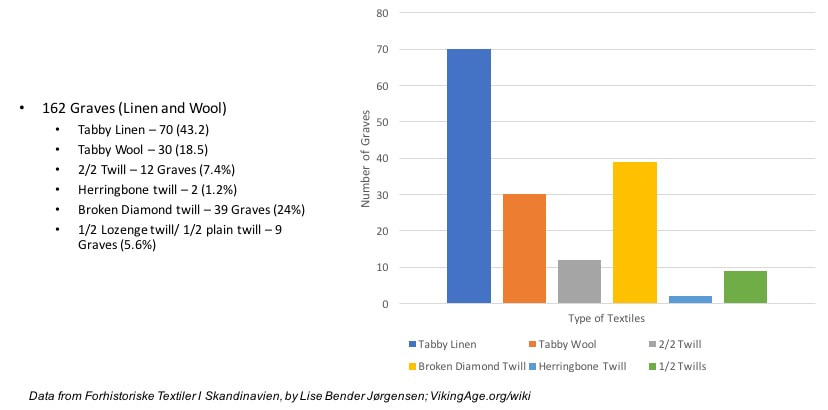

The notes above apply to this category also.

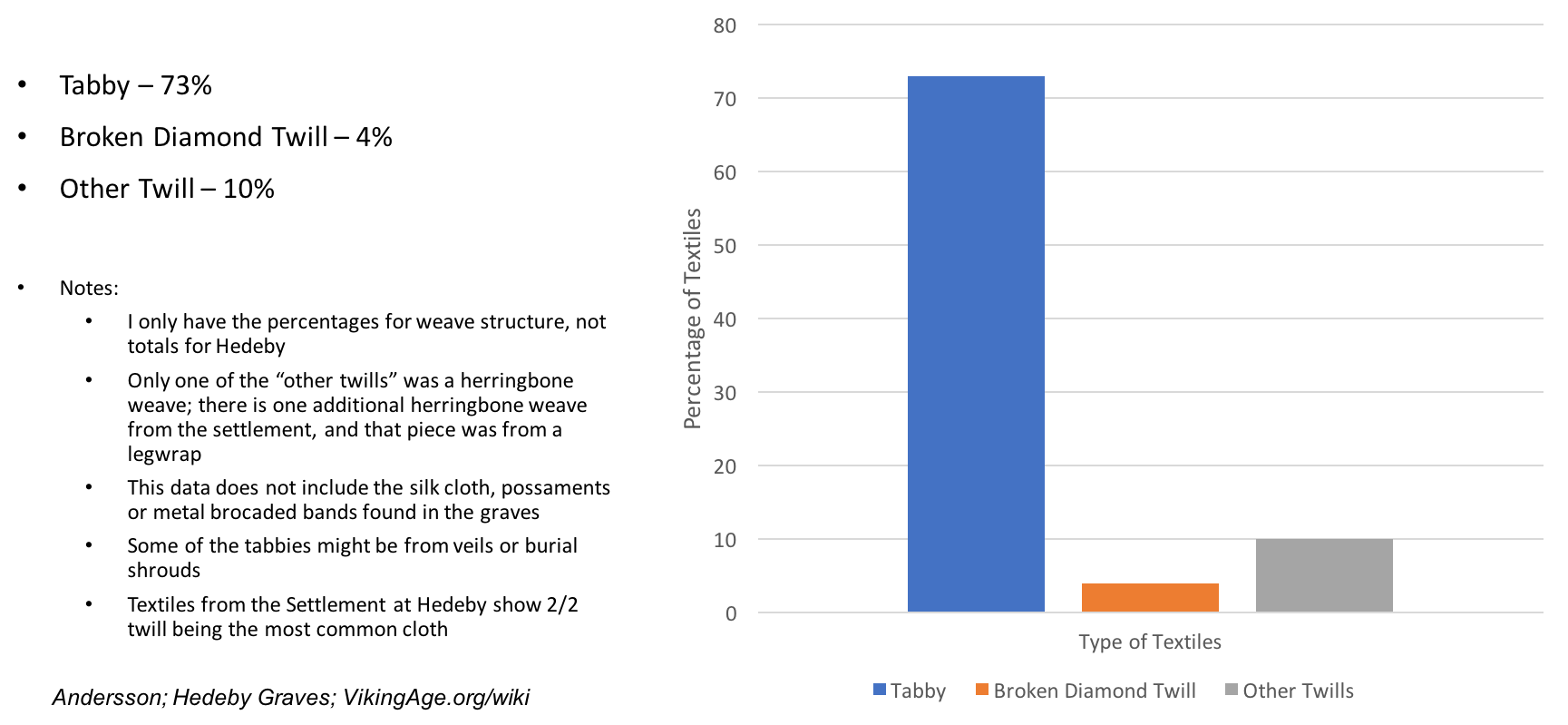

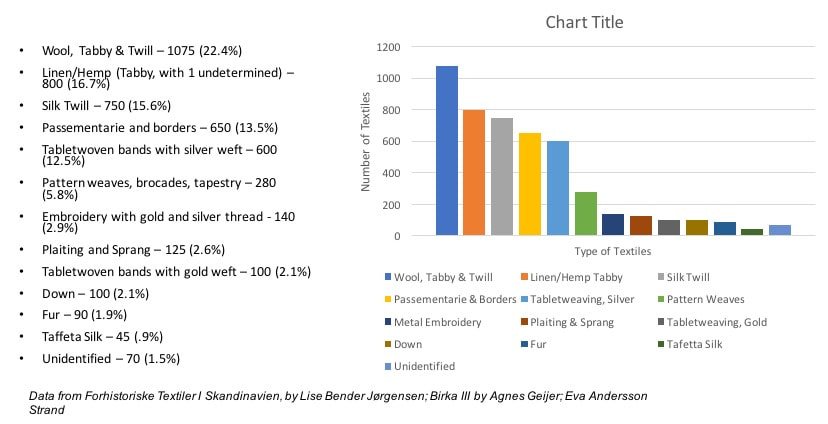

For Hedeby I had to reference the book Tools for Textile Production from Birka and Hedeby by Eva Andersson; Die Textilfunde aus der Siedlung und aus den Grabern von Haithabu by Inga Hägg; and VikingAge.org, as well as Jørgensen's work to obtain data for the chart.

Note that I only have the percentages for weave structure, not total number of fragments for Hedeby, and the percentages in Andersson's work are listed below. I believe it is, in part representative of the silk cloth, possaments or metal brocaded bands found in the graves. As mentioned previously, some of the fine tabbies might represent burial cloth.

It is also interesting to note that only one of the "other twills" is a herringbone weave, and the only herringbone sample from the settlement finds was from a legwrap. Also relative, the most common cloth from the settlement is 2/2 twill.

One of the nice things about Jørgensen's work is she does break out unusual segments of data, such as that from Gotland. This allows the reader to look at Sweden and Gotland (which tend to have very different types of grave goods) individually, rather than as a whole, which can skew the presentation.

For Birka I had two separate sets of data from which to work. One from the analysis in Jørgensen's book, and the other from Andersson. This first breaks it down into fiber types, as well as weave, but is based on number of graves, rather than number of textiles.

This chart was based on a chart produced by Inga Hägg that covers the Birka textiles and that was reproduced in Andersson's work.

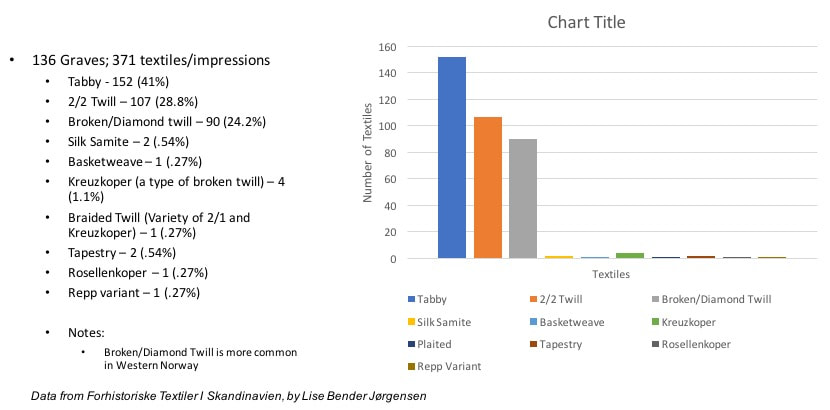

My only note here is that Jørgensen makes the comment that the Broken Diamond Twill is far more common in Western Norway, than in the South East.

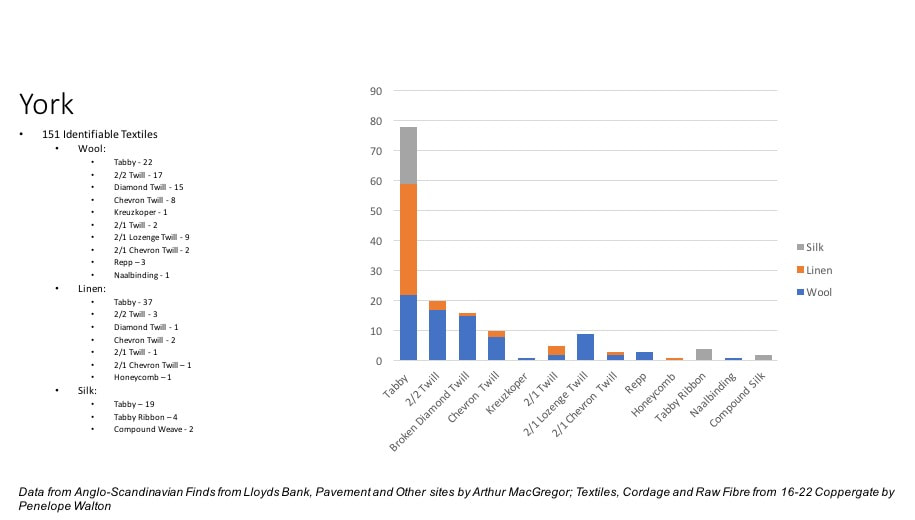

For York I had to compile information from Anglo-Scandinavian Finds from Lloyds Bank, Pavement and Other sites by Arthur MacGregor and Textiles, Cordage and Raw Fibre from 16-22 Coppergate by Penelope Walton. Some of the fragments might represent one piece of cloth, but the author's were not completely sure and hence they, and I, listed them separate.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed