- You have 6 hours to get your vehicle to parking after you arrive. You do not want to FAFO with the parking crew. You cannot keep a car in camp. Period.

- If you are parking a trailer in the lot, you HAVE to follow the rules. They are NOT even issuing warnings for this. They will just flat out tow you if your vehicle is parked improperly with a trailer (and you cannot leave a trailer connected to a vehicle in the lot either).

- The book you can purchase on site is NOT an up-to-date source of info for classes. It was NOT meant to be. In order to be available at a reasonable price, it had to be printed some time ago. Classes were added or canceled or moved after that. Your best bet is to print an UP TO DATE list from Thing before you leave or look it up online from site. thing.pennsicuniversity.org/

- Some roads are designated One Way this year. Know what they are and follow the rules, this is a matter of public safety.

There is a LOT of poison ivy on site this year, more so than in years past. Also, high weeds have chiggers this year, if you don't wanna FAFO with the parking crew, you definitely do not wanna FAFO with these buggers.

My classes are below:

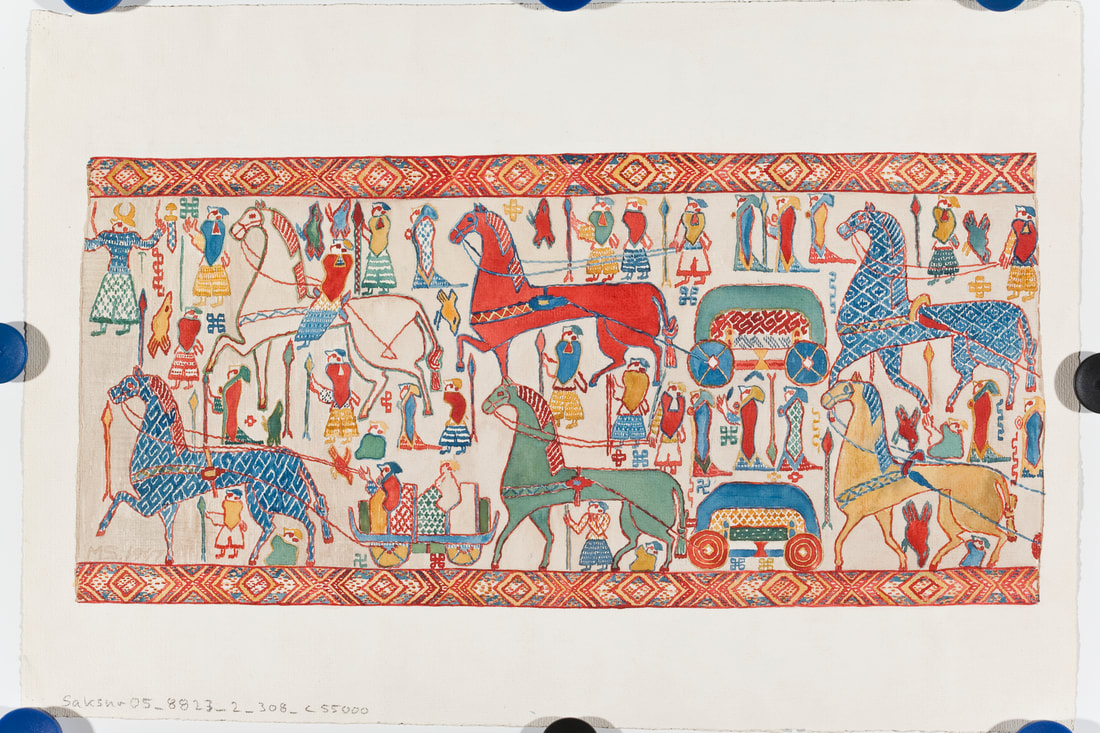

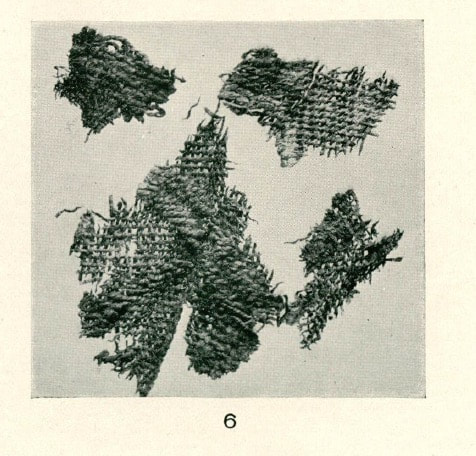

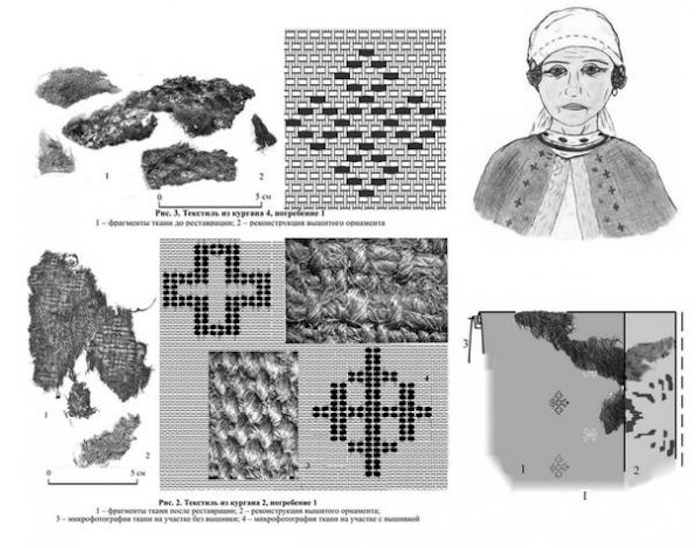

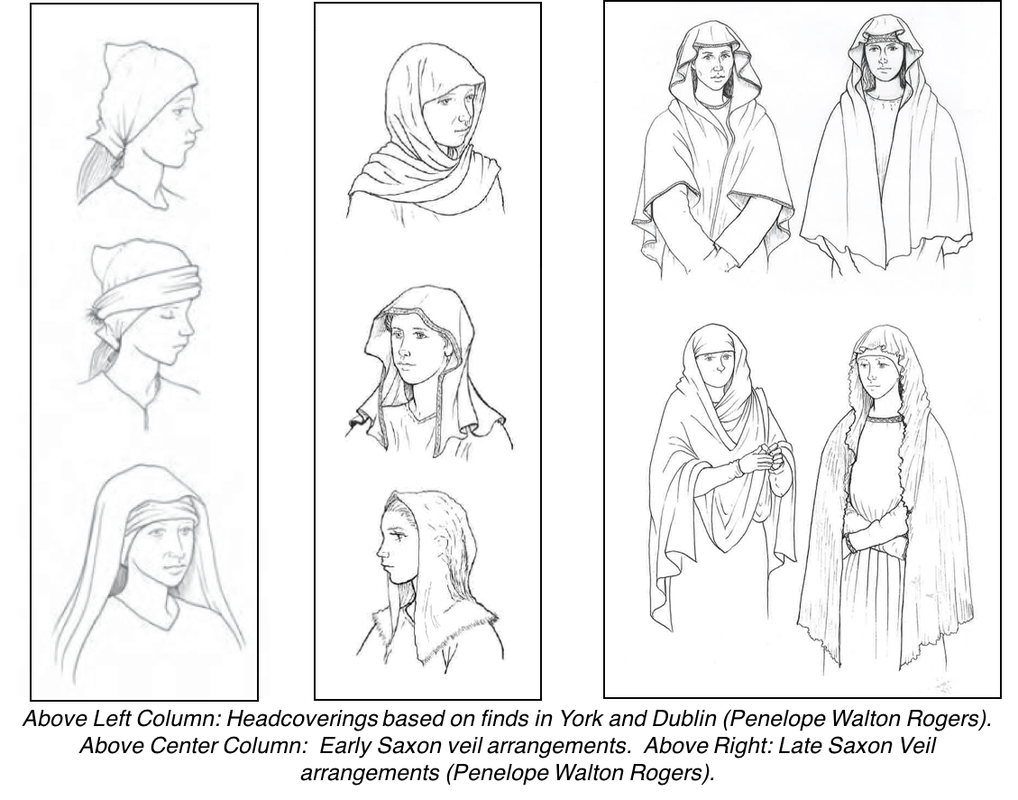

- 8/4 12PM A&S19 (2 hours) Celtic Textiles & Women’s Dress of Central Europe: Analysis of textiles from the Iron Age in Central Europe, along with information on dress accessories, period iconography, and burial practices. This class aims to help make informed choices for crafting women’s dress in the Late Hallstatt and Early La Tene periods in Central Europe.

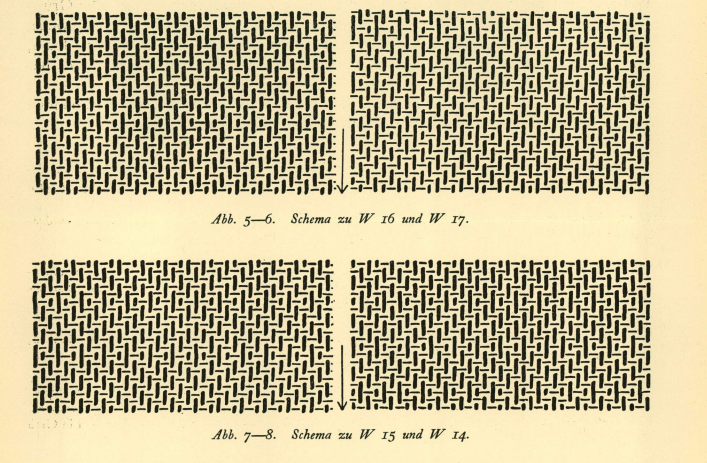

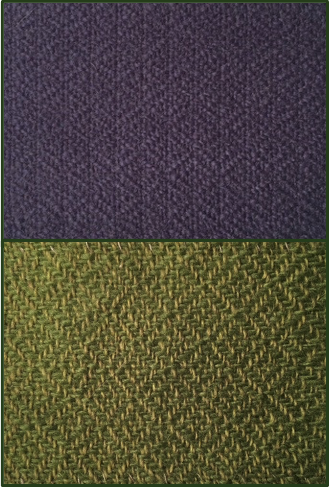

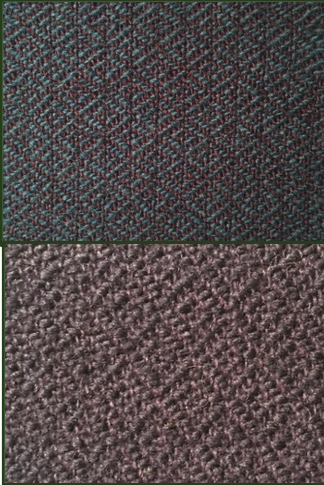

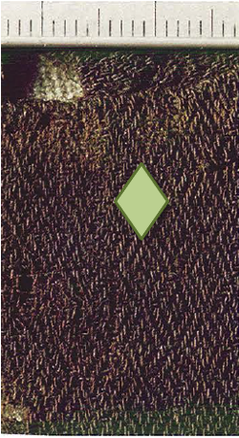

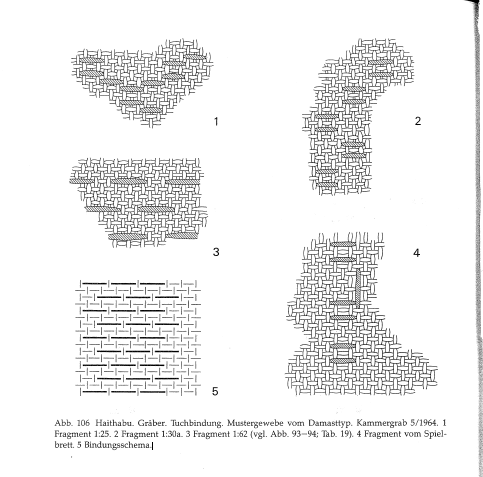

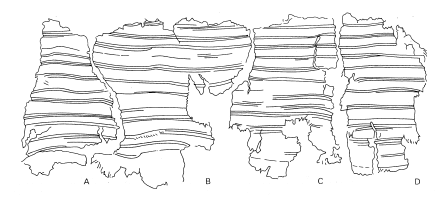

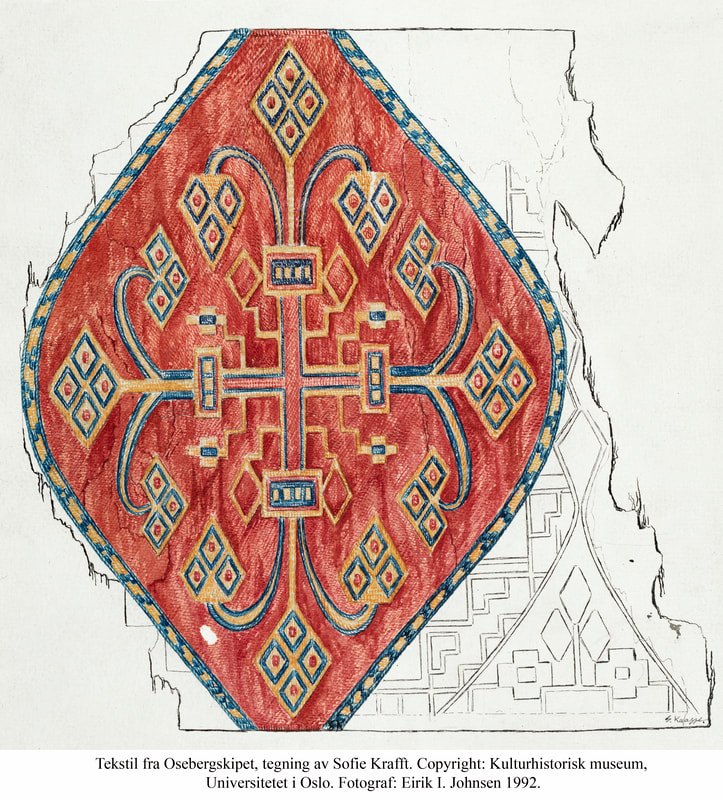

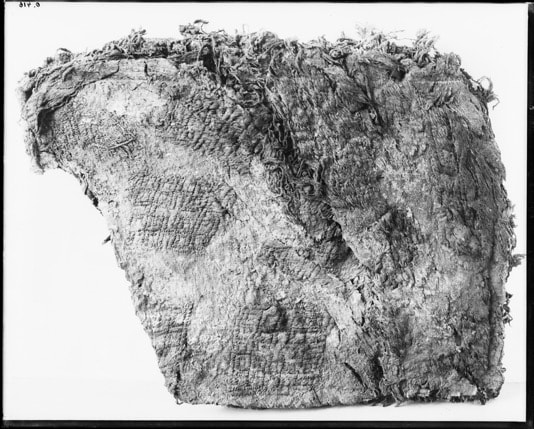

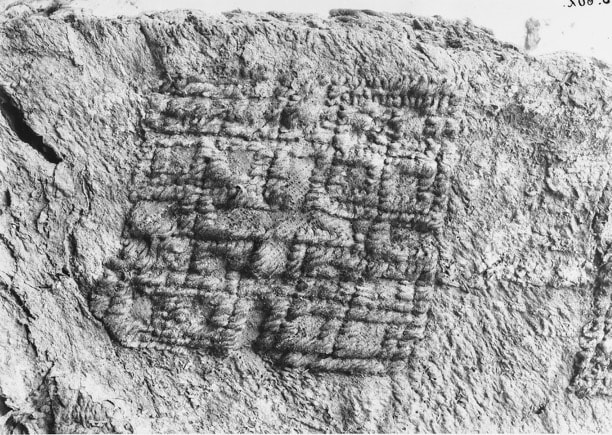

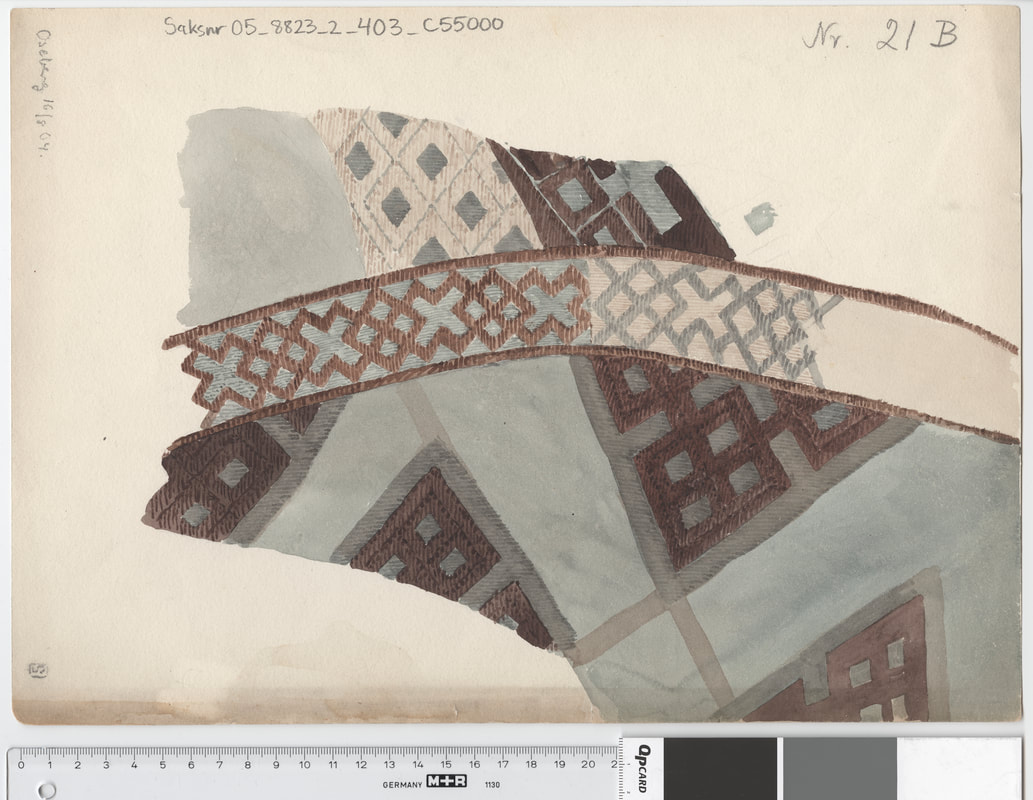

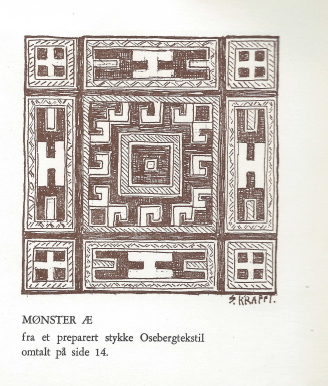

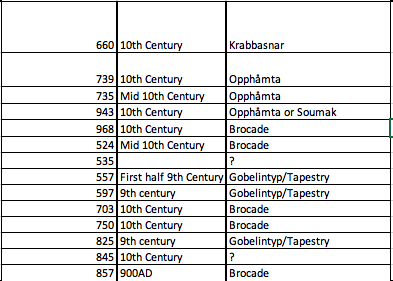

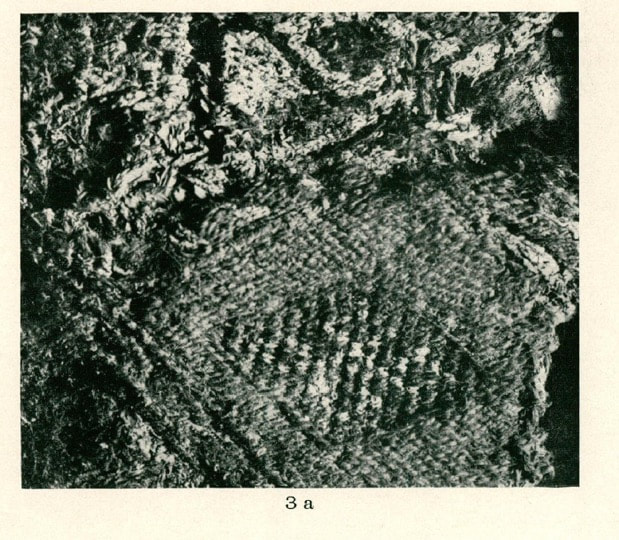

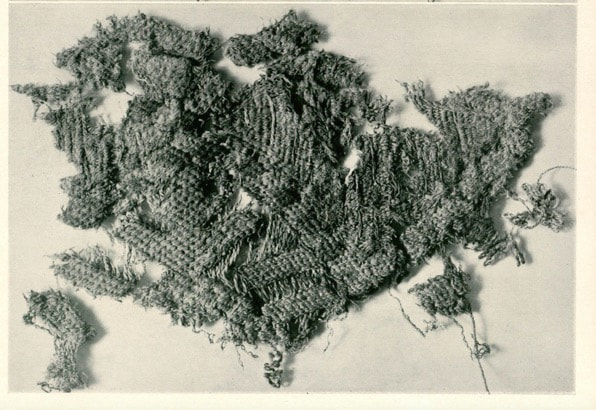

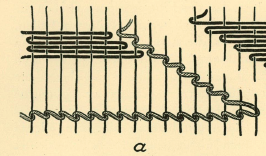

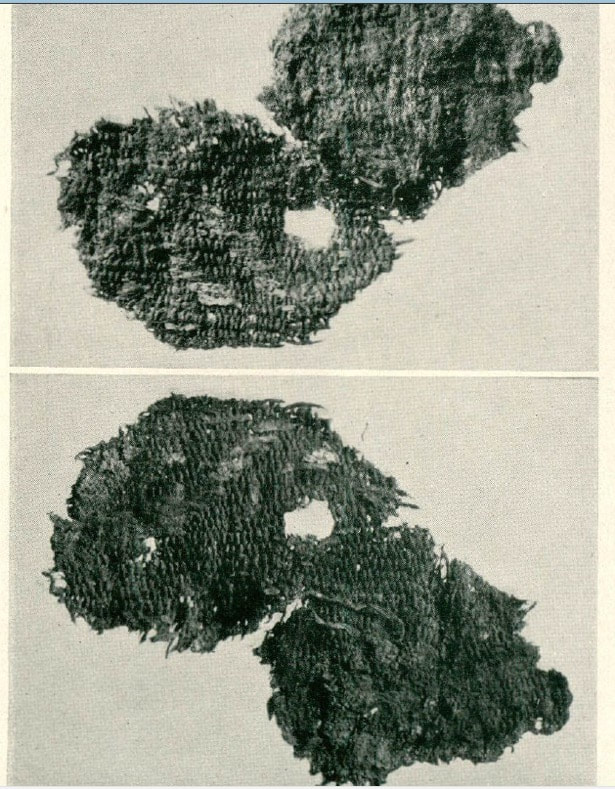

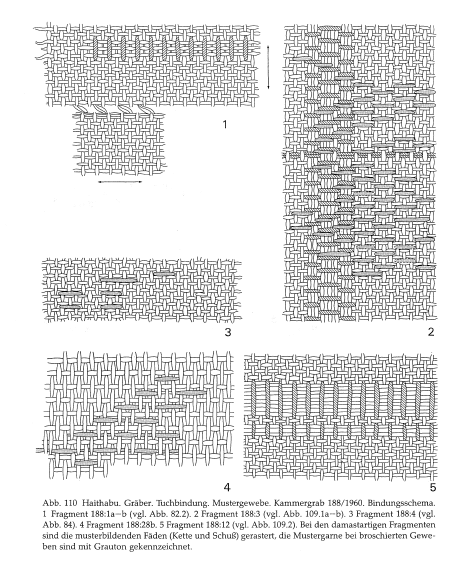

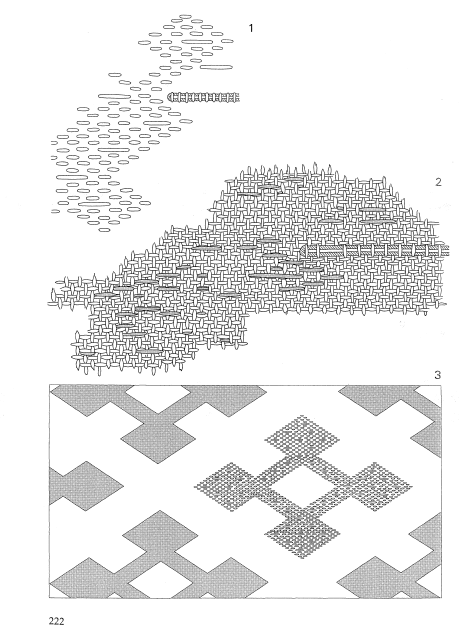

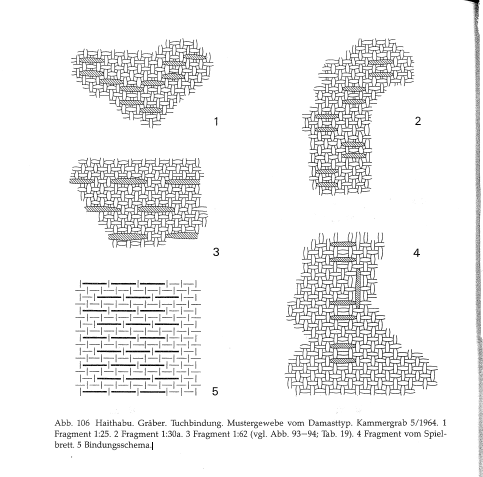

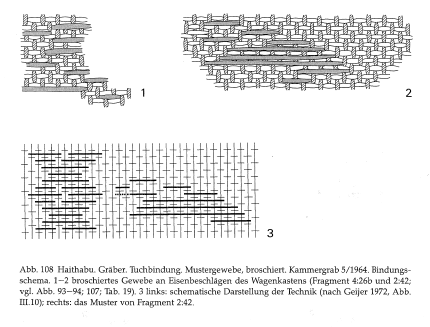

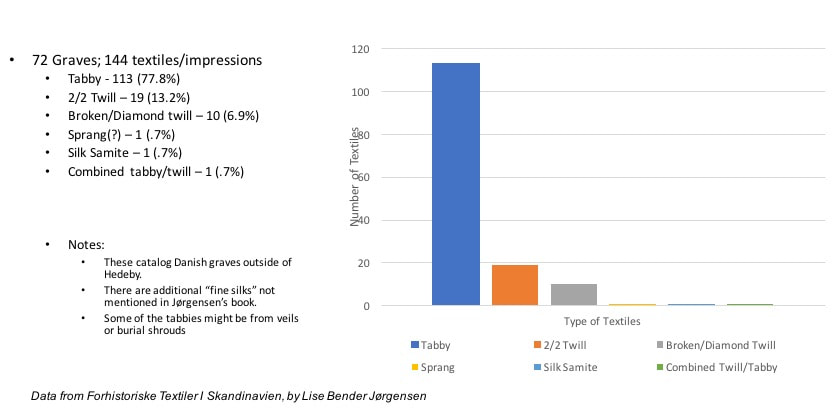

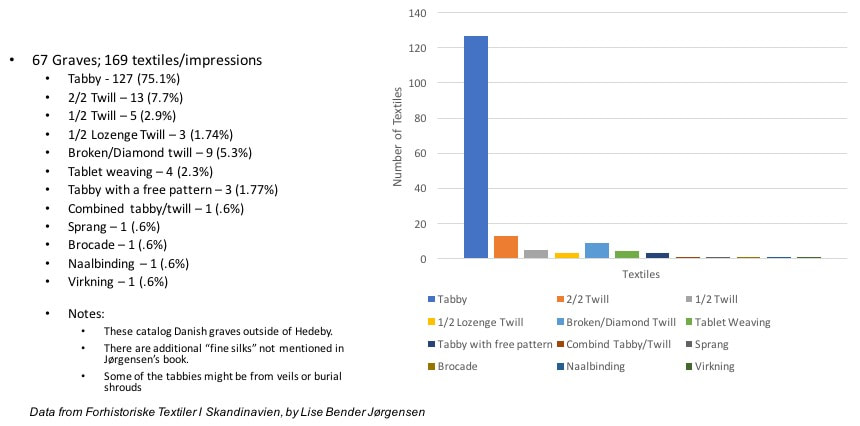

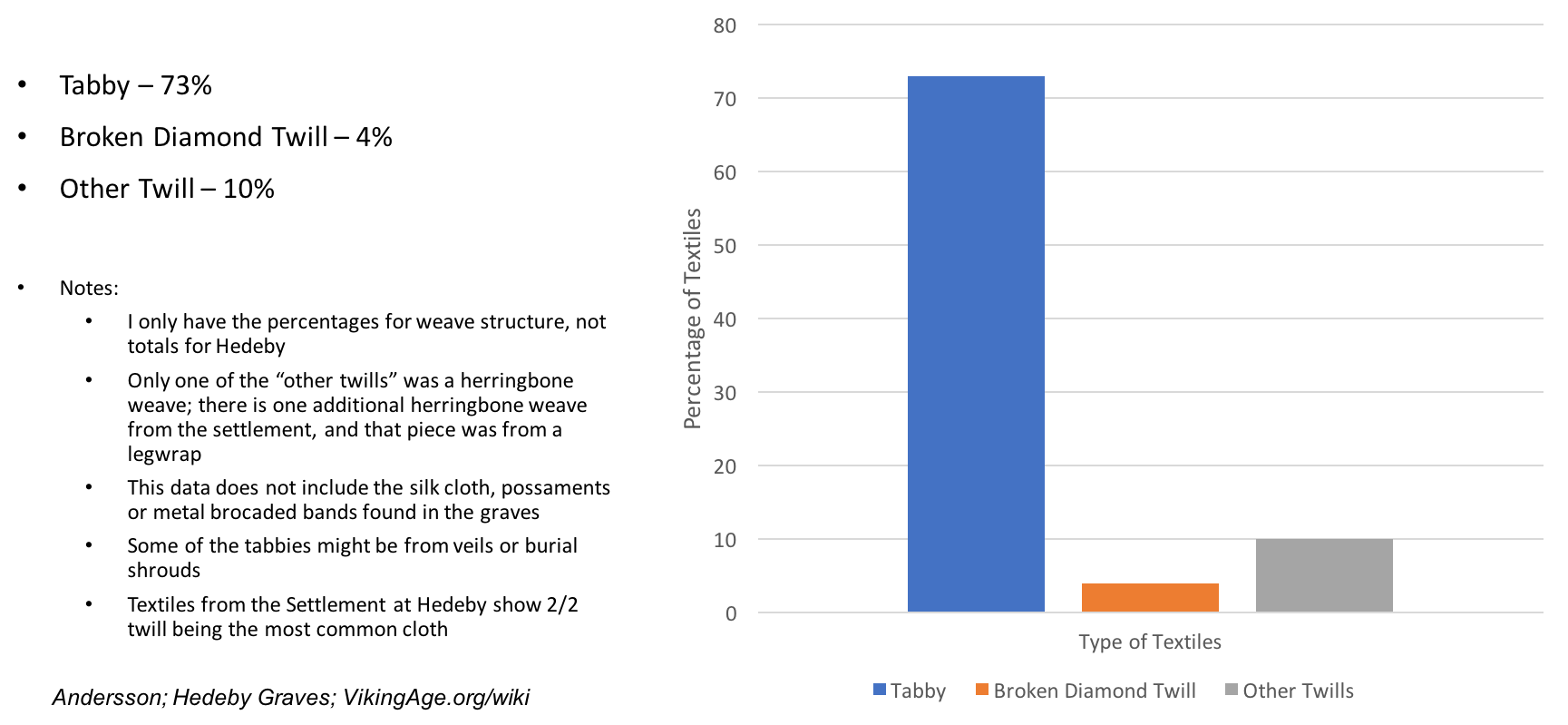

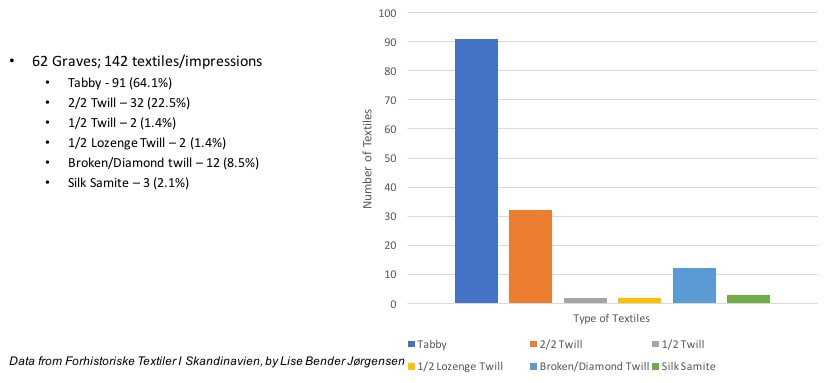

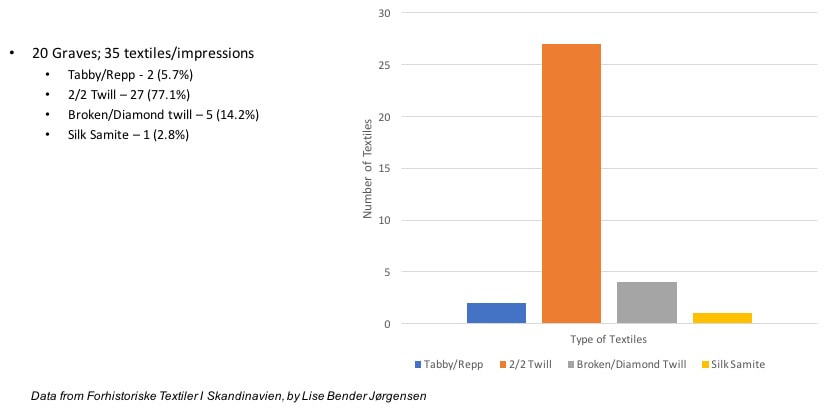

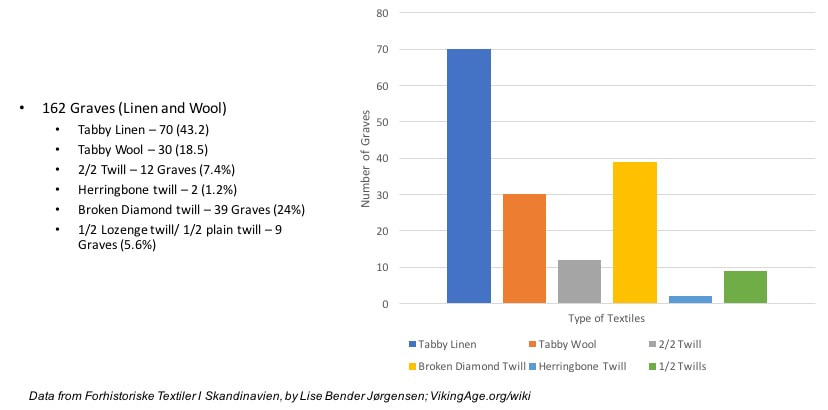

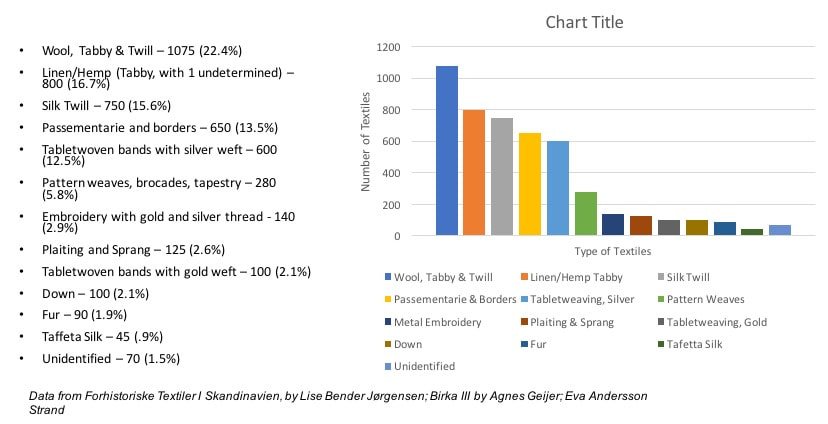

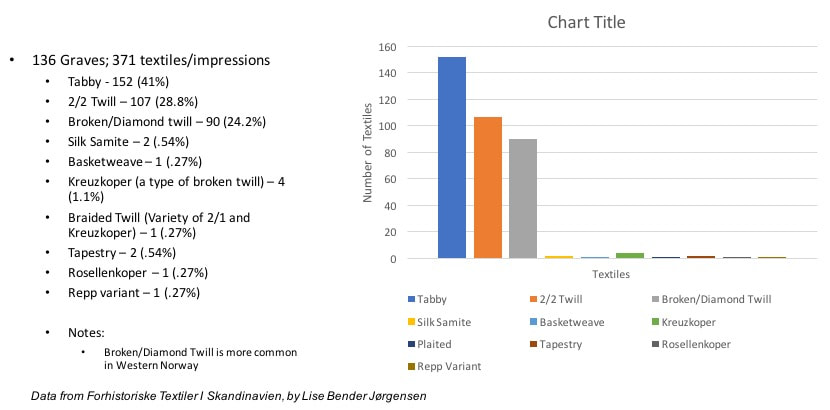

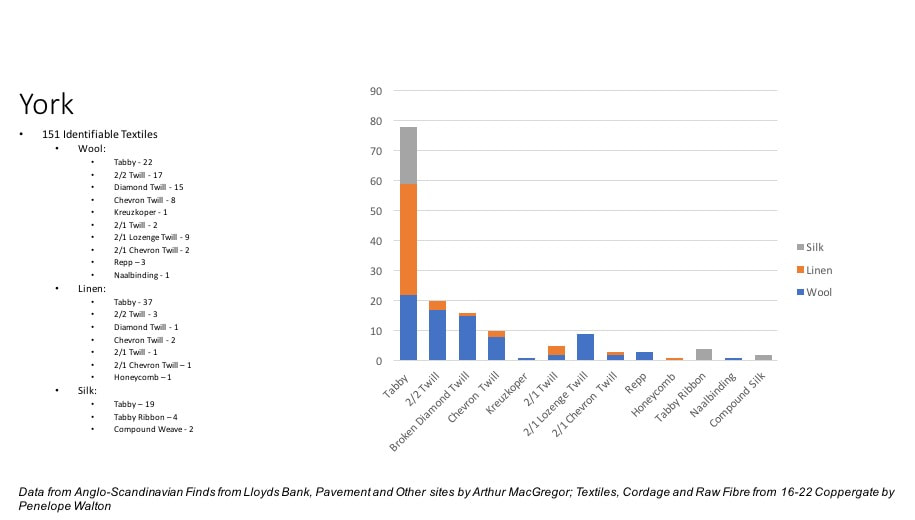

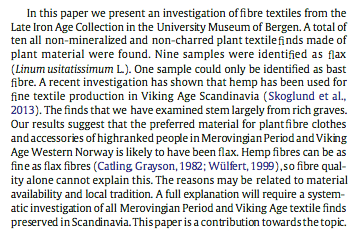

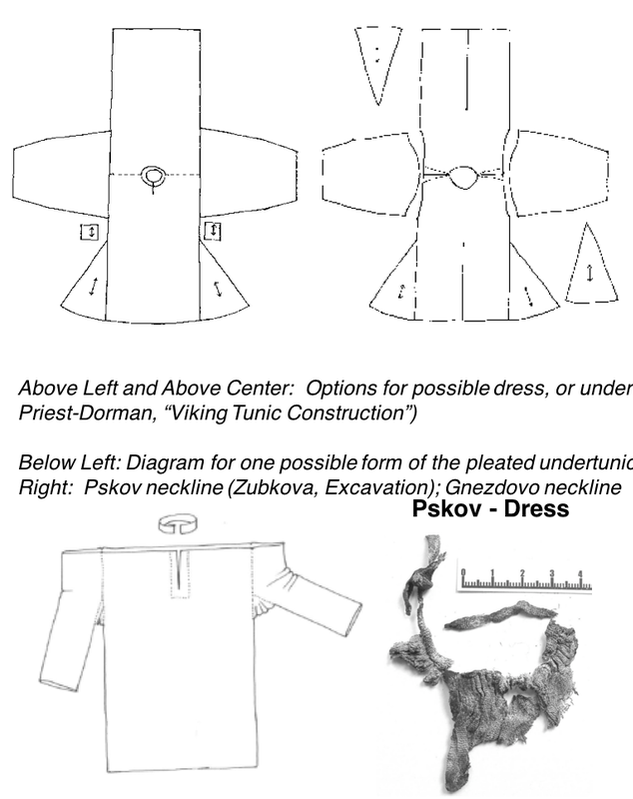

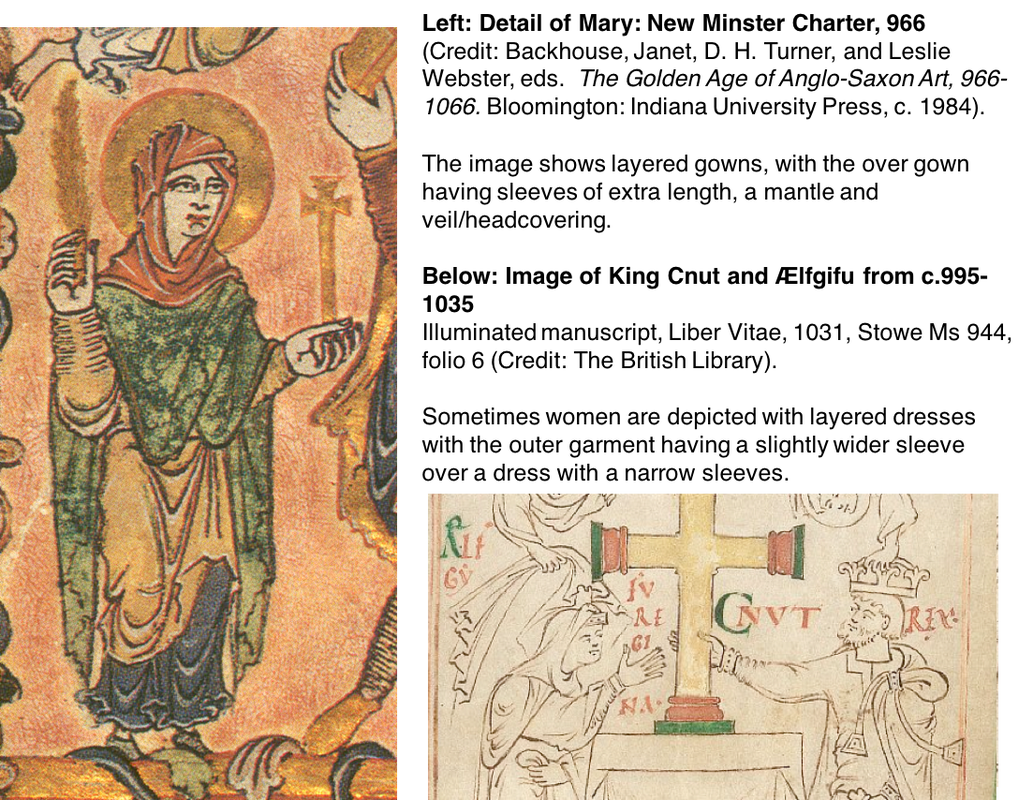

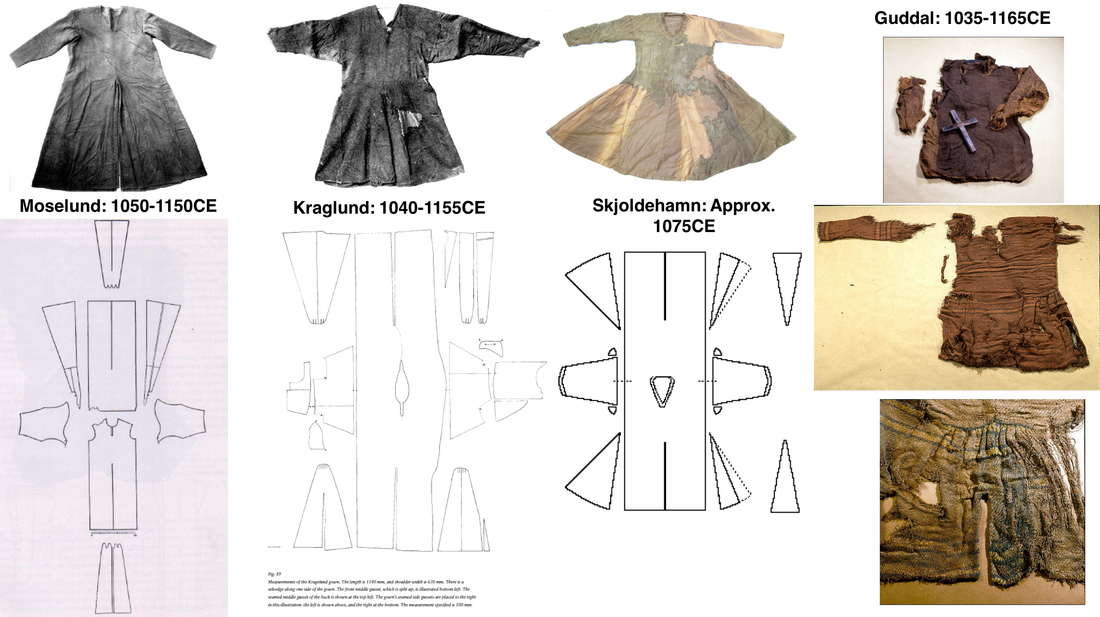

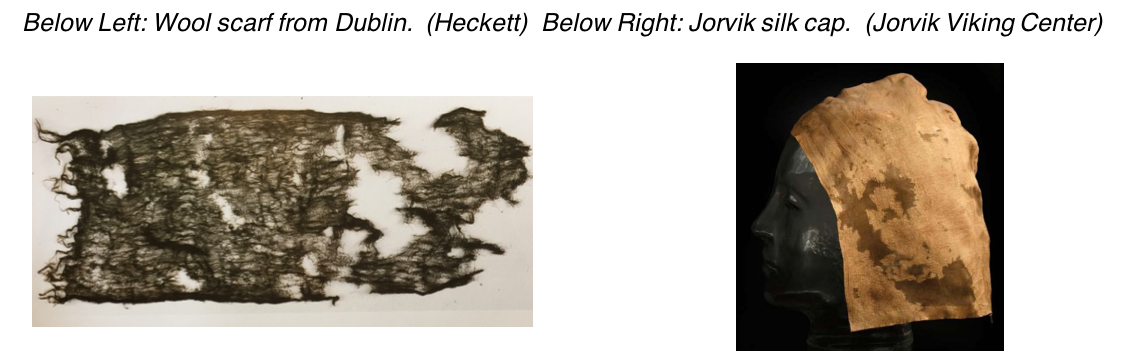

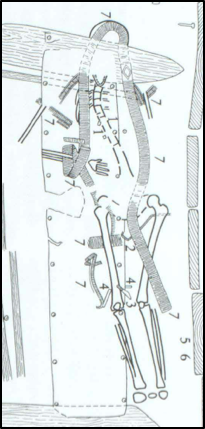

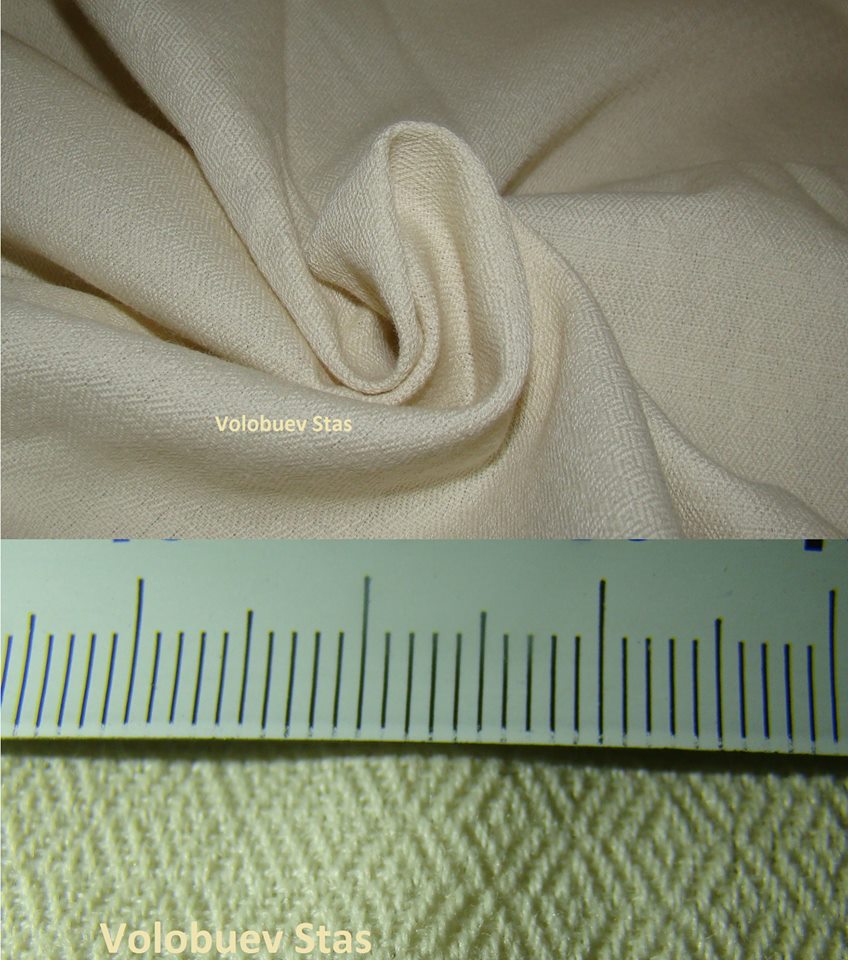

- 8/8 11AM A&S 15 (2 hours) Deeper Look at Textiles & Trim of Viking Age Dress: By looking deeper at both the textiles and the details from extant items, this class aims to help individuals make informed choices for crafting their garments. Textile examples will clarify the weaves and weights of period fabrics and there will also be discussion of possible modern substitutions. Additionally, practical details for finishing or embellishing garments will be explored and their history investigated. The goal of this class is to help the individual understand how daily life during the Viking Age could affect how textiles were crafted and worn.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed