Click the image below to read a lovely tale of how another individual found her place in the SCA.

|

I love hearing stories about how people discovered the SCA and fell in love with it. To find one's place amidst the ranks of artisans and fighters and to find a wealth of friends with a common Dream is both powerful and empowering. Likewise, I love to hear about how people who are becoming burnt out, or even disenchanted, are drawn back into the Society. It is important for all of us to remember that more often than not, it is the people around that provide those enchanting experiences for both newcomers and long-term members alike. Everyone has the ability to make a difference, and help flesh out the Dream for someone else.

Click the image below to read a lovely tale of how another individual found her place in the SCA.

1 Comment

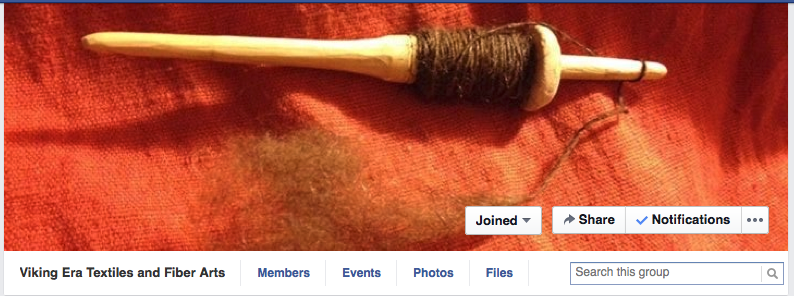

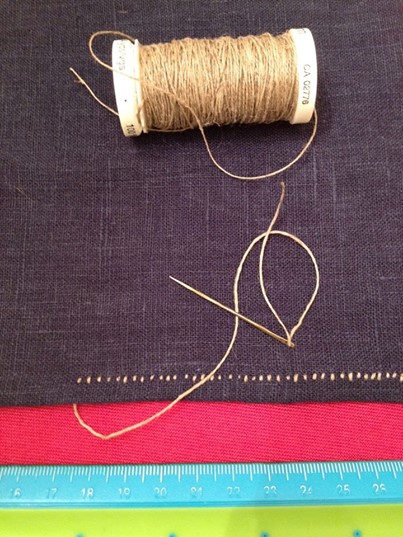

I thought I would share here that I started a new discussion group on Facebook for Viking Era fibre arts. This group is a place to research, explore, and share projects pertaining to historical fiber arts, textiles, and experimental archaeology. Focus is on craft of the Vikings, but other cultures that had influence on the Vikings and their work are also welcome (Saxon, Merovingian, Finnish, etc.) Every aspect of these arts are welcome on this forum, from the history of sheep, to fiber tools, fiber processing, spinning, weaving, dyeing, naalbinding and embroidery! Please share your thoughts, ideas, research and works-in-progress! You can reach the page by clicking the image below. Please join us :-) I also have a few projects that are coming along nicely. I have discovered that I very much am enjoying spinning flax. This week I finished spinning some 2-ply sewing thread from flax. It is a bit less than a millimeter in diameter and I am now using it to sewn a Dublin cap from linen fabric.

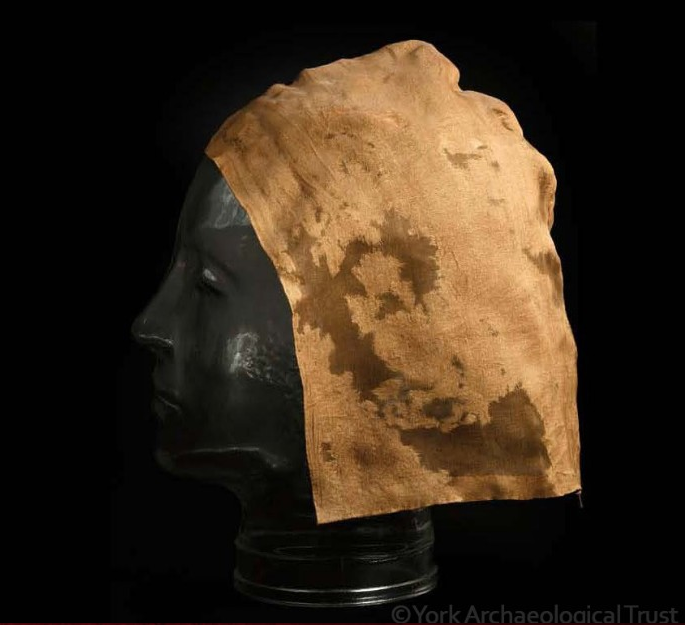

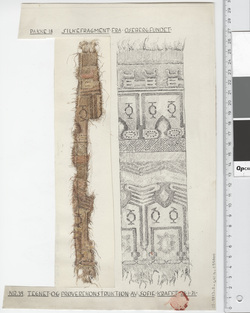

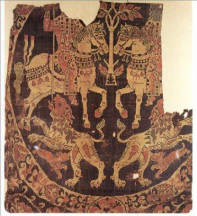

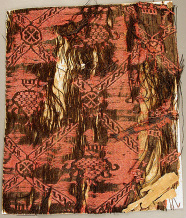

In addition to using the handspun thread for this project, I am also employing more period sewing techniques than I typically have been using. The hems are only 5mm wide, and rather than hemming with running stitches (which i can do quick, while still being very neat and even by using a very long, fine modern needle) I am using a hem stitch as was more common on these caps. I am trying to keep it to 4 stitches per 10mm and having them no more than 2mm long. I just might go blind doing this, but it seems to be working out well (even if progression is slow and the stitches are not as even as I would prefer). As I mentioned in my previous post about how fine the Viking fabrics could be (found here ), I have had quite a bit of reconsidering over the last several years of the difference in my initial impressions of what Viking fabrics would be like compared to the reality presented to us from archaeological digs. Their textiles could be quite fine, especially those worn by the wealthy. As a spinner and weaver, the very high thread counts in some of the extant fabrics makes my head spin. Some of the "Birka Type" diamond twills found at Ribe had 24-62 warp ends and 15-25 weft picks per CENTIMETER. (Bender Jorgensen, 62) That is a very, very fine piece of weaving. And fine weaving, of course, requires fine spinning. While I am nowhere near an expert spinner (having only been spinning since Pennsic 41), I can produce the equivalent of a 6/1 wool with some ease using a drop spindle. When weaving with a wool of similar weight I was working at 20 ends per inch, and while I could have packed in a few more threads per inch for a more dense cloth, it is still nowhere near the refinement of the Birka fabrics (or many of the others). I can spin a uniform thread a bit more fine with my spinning wheel, but not with hand combed Icelandic or Spaelsau and even with a commercially processed top it is not as fine as the extant fabrics suggest. I started to think about what was wrong... my fiber, my technique, my tools? All of these? I have a large assortment of spindles, including several that are quite light weight. But none would allow me to create the thread I wanted. I recalled something Mistress Rhiannon said in one of her spinning classes at Pennsic 42. We worked some with very large hand spindles to create a thick, lofty wool yarn and she mentioned something about medieval women using spindles in-hand. I started to wonder if I needed to use a supported form of spinning to produce an exceptionally fine thread but I had not yet had time to test out the idea. The idea recurred to me as I was beginning to search for tutorials on how to spin flax. I came across two different things that made me further consider that concept of supported spinning. One is a video of Norman Kennedy spinning flax thread (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FOk8vLgxfgE ) and the other was a fascinating blog and articles about 15th Century spinning (http://cathelinadialessandri.wordpress.com/spinning/). This left me wondering more about the process of supported spinning and if that was not, perhaps, how Viking women created their yarns. Certainly my own experiences with reproduction spindles would not let me produce satisfactory yarns via drop-spinning. The small low whorls had a tendency to spin very rapidly for a few seconds, then stop and backspin before I could stop it making the whole process rather nerve wracking. I opted, only out of stubbornness, to again try one of the most attractive spindles in my collection, when I first attempted to spin flax a few weeks ago. This is a spindle from Feed the Ravens with a Sami reindeer antler whorl. The first few yards was clumsy, but once I got the flax fiber drawn out so that the yarn I was spinning was exceptionally fine, the spindle behaved beautifully. The spin was fast, but long, and there was no abrupt stop with backspinning that I had noticed when spinning wool. I had come to a revelation that perhaps spindles and whorls could be far more specialized in their purpose than I originally thought. Things were made much more clear to me when recent research for something else to read "Textile Production at Birka" from NESAT 7. In this article Eva Andersson references the spinning studies done by Anne Batzer at Leijre. She stated that the only spindle capable of producing a worsted yarn of the finer period textiles had a 5 gram whorl and a spindle no more than 12cm long. Further noted was the fact that that spindle was incapable of producing heavier yarns. (Andersson, 47) Also mentioned in NESAT 7, in Ryders article "Human Development of Different Fleece Types" he makes mention of spindles and whorls being specific to certain types fleece in addition to being specific to the weight of yarn being spun (he also mentions the option of supported spinning). (Ryder, 125) All of these things set me to looking for a lightweight spindle and whorl. Both items were found (courtesy of a blog post by Lady Grazia Morgano) at shop in Germany carrying reproduction items for reenactors. (http://shop.pallia.net/index.php/en/) I purchased a 7 gram whorl and the smallest spindle shaft she sells (together they weighed only 19 grams) and at last was able to spin an exceptionally fine wool. You can see in the image below that the white Spaelsau yarn on the tiny spindle (yes it is fuzzy, but I was doing this experiment quickly) is almost as fine as the blue thread below it. The blue is Gutterman sewing thread (standard machine thread). It measures aproximately .152mm. My white yarn was .279mm and the green below it is a commercial wool single for weaving that is .345mm. In Viking Age Headcoverings from Dublin, Heckett mentions threads as fine as .2mm and there is mention of threads as fine as .3mm from Merovingian finds. I feel like I finally have figured out that tools were one major factors that were limiting my ability to reproduce the fine yarns used to weave some of the more exceptional period textiles. (Note that I understand that Meroginvian is not Viking, but it is rare for any article to mention the diameter of the thread, as typically only the thread count is given. This article referenced both factors which helps me to get a better idea of the relationship between diameter and thread count for Viking textiles.) The image below shows several spindles from my collection. The two on the left are among my favorites for spinning wool. They are both from the Spanish Peacock and are fairly lightweight with top whorls that are roughly 2.5 and 3 inches in diameter. I favor these for spinning wool that is about a size 6/1 though I can spin heavier on them as well. I tried the smaller with linen and could not spin it as fine as I did with the Feed the Ravens spindle and, honestly, I did not care for the way it felt spinning. The next spindle is an Ashford that was one of the first spindles I got. It is roughly 20 grams, and despite being lighter than the Feed the Ravens spindle, I had a terrible time spinning linen with it. (It worked excellently, however, for plying the yarn I spun on the Feed the Ravens spindle into a 2-ply sewing thread.) The next is a hand carved spindle made by Mistress Rhiannon that also did not handle the linen well, but I suspect that is as much due to the whorl I used on it. I need to test it again with a different whorl at some point and see if I like that one better as I love it with an extant lead whorl for spinning heavier wool. Beside that is a reproduction spindle with a soapstone whorl that I purchased a couple of years ago from Minerva's Spindle. I have yet to find the right fiber and yarn to make this one happy. I now look for ward to experimenting further. The Feed the Ravens spindle is shown here with very fine linen on it. I am now completely in love with this spindle for the spinning of flax. The spindle and whorl weigh approximately 29 grams. And at last, my new tiny spindle with a shaft of less than 7 inches and a 7.3 gram whorl. Together they weight 17 grams. I look forward now to testing this spindle with a variety of wools, as well as flax to see how fine I can spin a variety of fibers. In addition to exploring my collection of spindles and further experimenting with various fiber types on each one, I also still plan to do some experiments with in-hand spinning as a method of recreating some of the extant yarns as I do see it as a likely method of spinning in period. I would like to eventually be able to compare the results of the two types of spinning. Resources Andersson, Eva. "Textile production at Birka: household needs or organised workshops?", Northern archaeological textiles: NESAT VII: textile symposium in Edinburgh, 5th-7th May 1999. Bender Jorgensen, Lise. "Textiles and Textile Implements," Ribe Excavations 1970-76, Volume 3, 1991. di Alessandri, Cathelina. 15th Century Spinning website. Heckett, Elizabeth Wincott. Viking Age Headcoverings from Dublin (Medieval Dublin Excavations series B) (v. 6), 2003. Kennedy, Norman. "Spin Flax and Cotton with Norman Kennedy", Interweave Crafts https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FOk8vLgxfgE. Ryder, M.L. "The Human Development of Different Fleece-Types in Sheep and Its Association with the Development of Textile Crafts", Northern archaeological textiles: NESAT VII: textile symposium in Edinburgh, 5th-7th May 1999. Vanhaeke, L. and C. Verhecken-Lammens. "Textile pseudomorphs from a Merovingian burial ground at Harmignies, Belgium", Northern archaeological textiles: NESAT VII: textile symposium in Edinburgh, 5th-7th May 1999. I discussed Ottoman silks in my Ottoman Textiles series of articles last year, but wanted to take a few moments to mention Viking silks as the topic frequently arises on the Viking costuming forums. Often a newcomer will inquire about what types of fabric to purchase for garb and both wool and linen are always mentioned. When it comes to suggestions for trim, strips of silk are always mentioned. Occasionally someone makes the suggestion of using "raw silk" fabric for garment creation and while I think it is a fine substitute for linen or wool if you already have it in your fabric stash (or you find an incredible deal on it), this is never a fabric I would (at this point in time) choose to buy for use in my historic costumes. Let me start by discussing what raw silk actually is (and isn't). Raw silk is two things. The first is it is a fiber source in its pure, unadulterated form, just as "raw wool" is wool sheared from the sheep that has not yet had other processing. When discussing a woven textile by the term of "raw silk", we actually mean a fabric type called silk noil. This fabric is a byproduct of the silk textile industry. It is comprised of the short or chopped up bits of fluff left over from spinning better quality silks. The yarn often looks more like a cotton or wool than anything we think of as silk. It loses most of its lustre and has a very uneven texture. When woven, the fabric is somewhat coarse and highly textured and does not much at all resemble what people think of as silk. (In my experience it also does not often hold up well over time, has dye that tends to bleed out when it gets wet and sometimes even has a fishy odor when damp.) Mirriam-Webster has the word "noil" coming into use in 1624, but it is likely that silk noil, or something similar, became used as a textile much earlier in history. Revival Clothing has an article that says that low-grade silks were in use as early as the 12th Century, but that does not, however, suggest that earlier cultures had or used this short-staple fabric for garment production. (I have to note here that I recall reading somewhere once that in medieval Japan they wove a fabric that was termed "raw silk" that was woven from from silk that had not been degummed. I cannot, however, find that source again though it was, perhaps, Reconstructing History.) When discussing silk fabrics in Silk for the Vikings, Marianne Vedeler states that the extant silks are most commonly samite (a weft-faced compound twill), twill or tabby woven. They are very fine silks, but some of them did have imperfections in spin (occasional slubs) and sometimes uneven weaving. This however, is in no way indicative that silk noil was used by the Vikings (or even produced at the time) and even a less well crafted example of silk from the Viking graves was more fine and used a longer staple than what we know of as silk noil. Consider also that even the period fabrics characterized as being of lesser quality had thread counts of 45 threads in the warp with 60 in the weft (and the weft was often unspun, which makes it very much unlike silk noil). Those thread counts (which get much higher as well) also serves to show how different these Byzantine silks were from what we know as raw silk fabric today. My suggestions for silk trim (as silk brocades are unaffordable) are to look for solid colored silk twills or patterned jacquard woven silks with, that when cut into strips, would not be identifiable as something more modern. A good place for such patterned fabrics are Indian silks often sold as fat quarters on ebay or etsy. Some sellers also carry silk remnants from the designer tie industry, and those fabrics are most commonly nice weighty twills that have a lovely drape. On occasion, I even use dupioni (a plain weave fabric that has the wonderful lustre and rich color one would expect from silk). This is more slubbed than the Viking silks but given that some of those also evidenced some slubs in the weaving, and we only use small strips as ornamentation, I think this is a fairly economical alternative. By way of example, look at the image of the highly textured, almost fuzzy looking, silk noil sold by Dharma Trading. Then compare that to a Viking silk cap from Jorvik, a fragment of Byzantine silk that is considered to be similar to one of the pieces found at Oseberg (Krag), silken ties from Mammen, a drawing depicting one of the Oseberg textiles and another Byzantine silk from the period. These historic examples are quite different from our silk noil.

Resources

|

About Me

I am mother to a billion cats and am on journey to recreate the past via costume, textiles, culture and food. A Wandering Elf participates in the Amazon Associates program and a small commission is earned on qualifying purchases.

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

Blogroll of SCA & Costume Bloggers

Below is a collection of some of my favorite places online to look for SCA and historic costuming information.

More Amie Sparrow - 16th Century German Costuming Gianetta Veronese - SCA and Costuming Blog Grazia Morgano - 16th Century A&S Mistress Sahra -Dress From Medieval Turku Hibernaatiopesäke Loose Threads: Cathy's Costume Blog Mistress Mathilde Bourrette - By My Measure: 14th and 15th Century Costuming More than Cod: Exploring Medieval Norway |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed