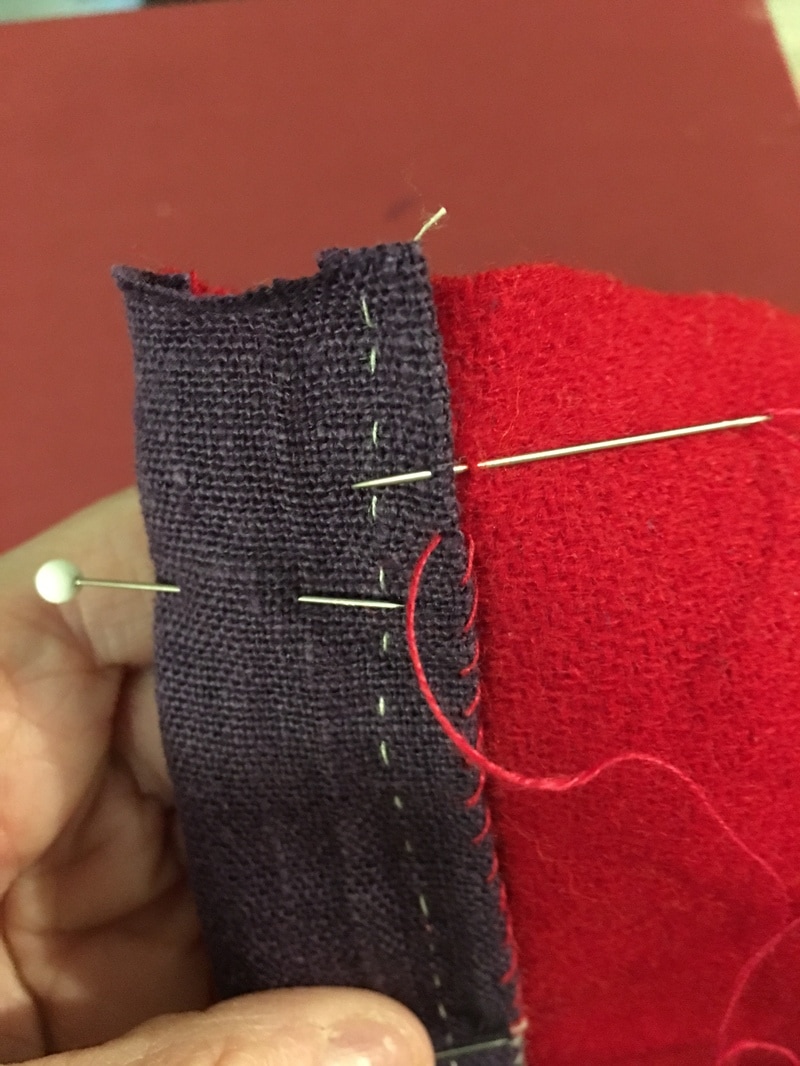

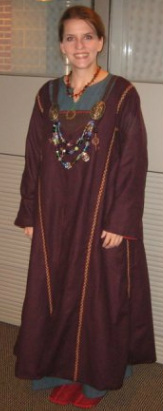

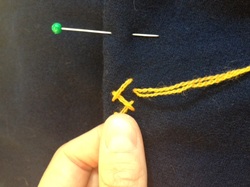

Anna's Hittite noble woman's dress (photo credit to Anna)

Anna's Hittite noble woman's dress (photo credit to Anna) For those who have not met her, Hypatissa Anna Dokeianina Syrakousina, runs the blog Anna's New Rome, and is a Baroness and amazing researcher and artisan in the SCA. She is also mundanely a historian, and that shows in her work, but I also think that this specific project really shows how others can make a step forward into new areas even without modern credentials to back them.

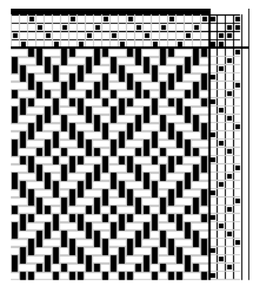

Her COVID project was Hittite clothing. This is (I think) and unexplored are in the SCA and I love that people are starting to step away from the things we see at every event and digging into lesser known cultures or periods.

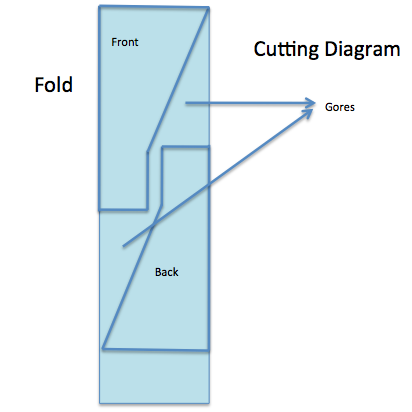

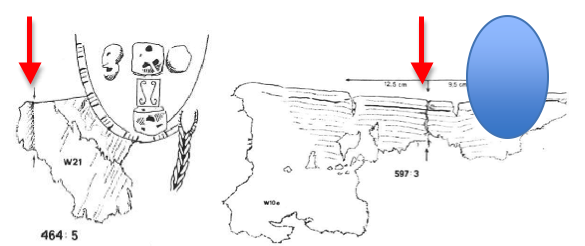

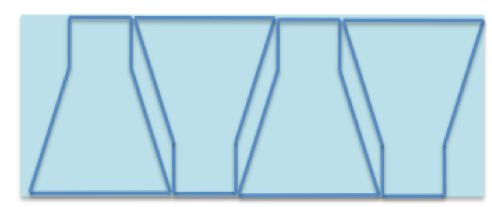

Here entire thought process is part of her blog post which can be found HERE. Please take your time to read it and check out the photos of the two outfits she presents as part of her first draft of this work.

- It is well, and simply, organized. She gives a brief introduction on who the Hittites were. This is key because it is a lesser known culture in an SCA context and this allows the reader, who might love the outfit enough to want to craft one, to be able to also relay that information when someone complements their garb.

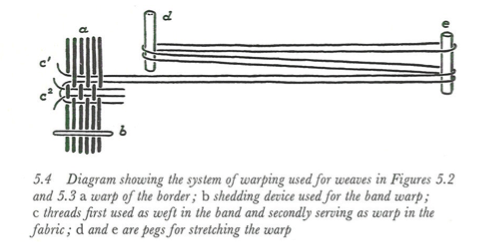

- She was starting fresh with this project (her area of expertise is Byzantine), so she gave a run-down of the types of sources there are, and what she knows about them.

- As she lists her choices, she gives the rationale behind each. This helps others understand they why's behind what they see and also might inspire other ideas for things to try.

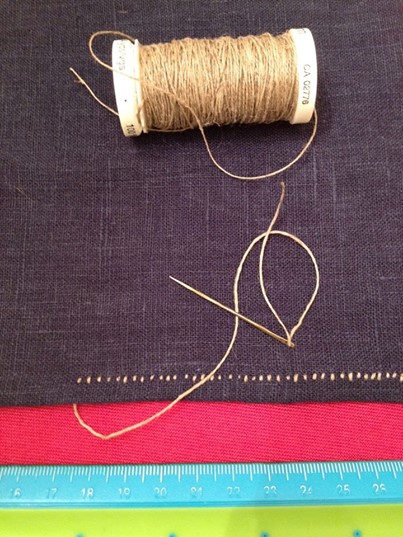

- Photos! Nice, clear photos that make the garments easily readable to others.

- Observations - this is one of the best parts of this blog post. She already is learning what works and what might need changed, so that she (and the reader) can take the next steps better informed.

I do want to call out one additional, and very key, item. Early in her post she makes the statement, "At this point, as the research appears to be super-new, I understand that this body of work will raise more questions than it will serve as answers, and I am willing to bring forth that needed dialogue, and accept changes will need to be made this early in the study. As far as I know, I am the first SCAdian, and possibly scholar/experimental archaeologist to try this. Please be patient with me as I iron out the kinks, and work to determine the best patterns and ideas before adding a ton of information that may not be correct. I know that some of this reads a bit choppy, I plan to flesh it out as I continue to build my arsenal of sources."

I think that sometimes we can be paralyzed with the idea of starting a new work, especially if it is something less well known. There can be fear and trepidation of somehow doing it all wrong. Be honest as to where you stand with the work and how far into the process. Every single thing we do in the SCA had a start somewhere. At one time all the Viking women were wearing two tea towels pinned at the shoulders and the more we learn, well, the more we learn.

Part of working with history in the manner in which we do is accepting that this is an ever-evolving science, in our own personal work, as a group of re-enactors as a whole, and in the broad scope of historic studies in the world today. We all start somewhere, and it might not be right the first time around, this is why we document things, share them, discuss them, research more, and then revise the whole process. Admitting that we do not know everything there is to know about something (even if we are currently wearing it) is not something to be ashamed of, but rather it speaks to our curiosity and our willingness to keep learning. Baroness Anna is already digging into more resources and talking to others who work in this field to help expand her work in the area, and I absolutely am looking forward to seeing more.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed