Weaving

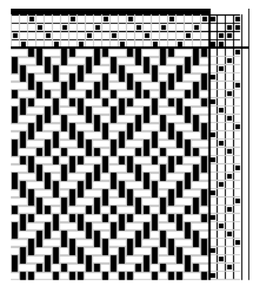

Because twills, of various sorts, were more common than tabby (plain) weave in Scandinavian finds of wool from the Viking Era (Welander, et al. 167-168), I chose a broken diamond twill weave structure from Birka that was common throughout the Viking world.

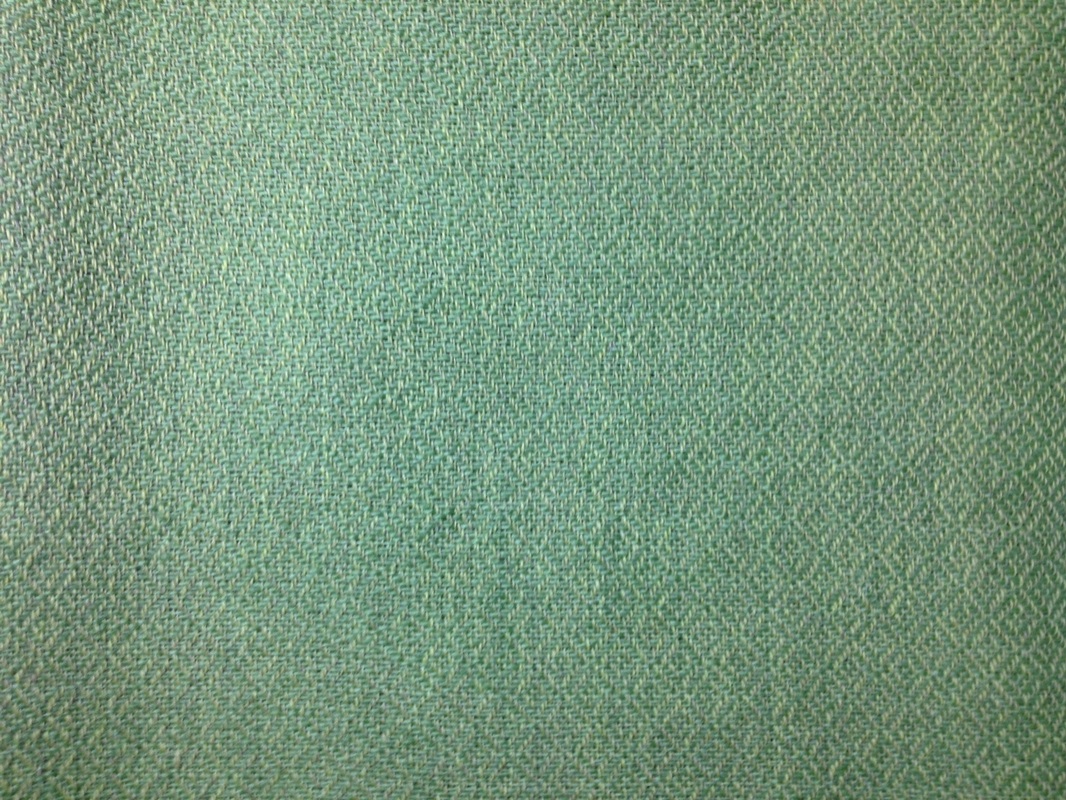

For yarn, I wanted to use singles as that was what was most commonly used in extant examples for garments. Singles are unfortunately not easy to find in the fine yarn I envisioned for the project. I was got lucky enough, however, to have a friend gift me a very large cone of very fine weaving wool that was single ply (aprox. 20/1, maybe 24/1). The color was a very pale green so I tried to purchase a similar color in the commercially available Borgs Faro yarn (6/1). The color match was not as close as I had hoped for, but the two look nice together in the final fabric. Note that many of the woolen twills available to reenactors have lovely contrasting colors in the warp and weft, but because this practice was uncommon in period, I did the best I could to use colors that were close in hue and value.

Even though the the base color was chosen for me, I also made sure that the color was attainable with period dyes. Both Penelope Walton Rogers and Jenny Dean have demonstrated that there were yellows and blues (weld, dyers broom and 'yellow x' for yellow and woad for blue) available in period and I know the two can be used together in an over dying process that allows for a range of greens. (Walton - Dyes, Dean)

In addition to my desire to use singles, I also knew that I wanted to reflect the disparity that was often seen in grist of the warp and weft yarns. A thicker weft, as is common in Viking finds, allows the weaving to progress more quickly and allows one to use both a strong, fine, strong warp and a more softly woven weft (for added warmth as woolen style spinning allows air to be trapped in the fibers and offer more insulation).

In the end, I did opt to use the Faro yarn as the warp, rather then the weft (though the weaving would have gone quicker the other way) as the yarn that I was gifted had passed through several hands and I suspect that it is quite old. I did not want to risk warping with that and discovering that it would start to fray or break.

Because I do not have a full-scale warp-weighted loom (see my article on this blog about my table-top version if you want to know more about these looms), I wove the fabric on my Oxaback Lilla countermarche loom.

I used four shafts on the loom and had a total of 800 heddles resulting in 20 epi for the warp. My weft wove in at 32-34 ppi. This, I feel, is about the low-middle end of the range for thread count in period grave burials. There are extant examples of wool that can have a thread count of over 100 threads-per-inch in one system. (Christensen and Nockert, p177-182).

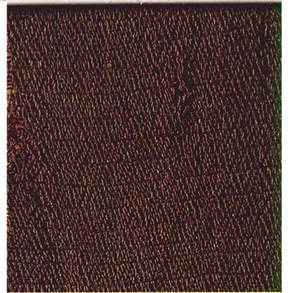

Below you can see the fabric on the loom and a detailed shot of the early stages of the weaving.

The other major issue I had was with tension along the right hand side of the loom. I adjusted it several times as I went by slipping folded paper into the warp, but the final fabric had a ripple to that edge because of that issue.

After the weaving was complete, I cut the fabric from the loom and wet-finished it in warm water and then pressed it with an iron. I did not use exceptionally hot water, nor did I agitate it, as I did not want to start the fulling process as fulling did not become common until after the Viking age. (Walton - Coppergate, p 94)

My final fabric was by no means perfect, but I learned a great deal throughout the process and am happy to have, at last, woven my own fabric for a garment.

Dress Construction

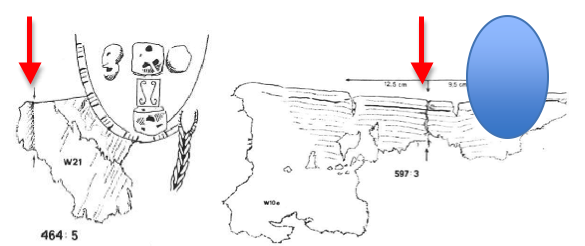

The loops preserved within the brooches suggest they held up a garment (or garments), rather than than having a garment pinned through a solid piece of fabric (though it is possible that earlier in history -or even during the Viking Era in Finland- that these brooches fastened a peplos style garment - the possible predecessor of the hangerock). Often brooches, such as one set found in Birka, as well as those from a Scandinavian woman buried in South Yorkshire, have a pair of loops on each brooch, one at the lower end of the pin, and one at the top. (Speed and Walton, 76) Sometimes there were multiple sets of loops, which could be evidence of a wrapped garment or of cords that suspended tools from the brooches.

As the Haithabu pattern piece is one of the more complete pieces (allowing one to extrapolate construction theory), I often use this as a starting point for my recreations of this garment.

In an effort to explore some of the speculations regarding the constructions of the Haithabu dress, I have experimented with a variety of pattern shapes. My reasoning for not always recreating what exactly I felt this dress looked like is that there was more than one manner of cutting a tunic in period, and likely, there was more than one manner of cutting the elusive apron dress as well. Further, there is so little we know about the Haithabu fabric in terms of placement, number of pieces, and additional pattern pieces that even the typical representations of the garment are based largely on speculation.

Aside from the Haithabu dress remnant, there are also what appear to be seams on two separate textile fragments of apron dresses from the Birka grave finds. Some recreationists have made the assumption that these are side seams. Depending on the size of the wearer, this is possible, though it is just as likely that because the seams are placed not far from the brooch, closer to the front of the garment, they might actually mark the edges of a center front panel rather than the sides of the garments. I recreate garments based on both theories.

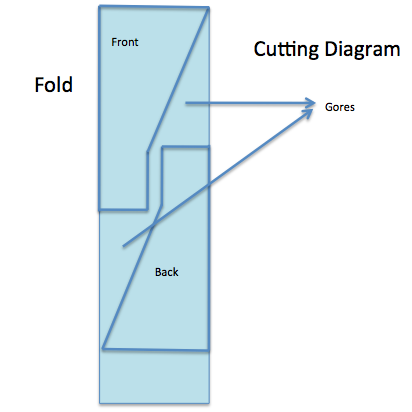

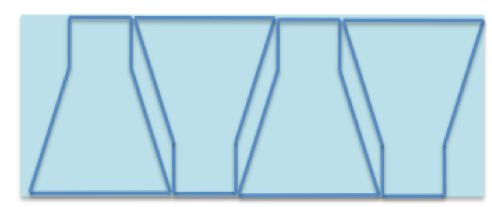

For this particular garment, I have chosen a cutting diagram that involves very minimal waste as I believe that during the Viking era that would have been a of exceptional importance. When using the cutting diagram below, the dress is cut from minimal fabric with very little waste. Because of several weaving errors, however, I chose to use the same shapes, but arrange the cutting differently to allow me to make best use of the better portions of my fabric.

My plied weft yarn to use as sewing thread.

My plied weft yarn to use as sewing thread. The stitch types I chose were all present in various archeological finds. I overcast the edges of the fabric with a whipstitch to prevent fraying. A running stitch was employed to fold the edges of each cut panel. The joining seam is a butted seam, completed in small overcast stitches placed close together. These seams can be stress points and I prefer them stronger than the stitches I used for the folded edges mentioned above. The double fold hems are completed with a running stitch. (Baker)

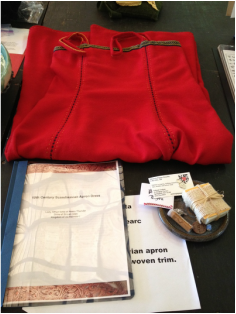

Completed Handwoven Dress

Additional Cutting Layout

My cutting diagram for this dress is based heavily on finds from Birka, and the spacing between the brooches and seams. This makes the idea of a dress constructed of four panels quite conceivable.

Below, I present to you a list of materials used in my recreation of an apron dress. With each item is the rationale for that specific choice.

The fabric is a modern machine-woven Shetland wool.

The weave is a 2/2 twill. Examples of this can be found from Scandinavia to the British Isles. (Walton - Coppergate 1749; Christensen and Nockert 177-182) Twills, of various sorts, were more common than tabby (plain) weave in Scandinavian finds from the Viking Era. (Welander, et al. 167-168)

While it is certainly possible to find nice twills, both diamond twills and herringbone fabrics today are hard to come by, tend to be expensive and often have the warp and weft in different colors allowing the pattern to be more visible. This practice of multiple colors in a weave, however, was not overly common in period textiles I have seen or researched. Based on all of this, I chose a common period weave that I could readily get in a monochromatic fabric at reasonable cost.

On my fabric, there are approximately 25 ends per inch on both the warp and the weft. This falls within the low end of the range for the textiles from the Oseberg ship, as well as other finds (Christensen and Nockert 177-182). Anne-Stine Ingstad noted that typical of Viking era fabrics to have a higher thread count (and finer fibre) for the warp than the weft. Unfortunately, this is not something you can commonly find in mass-produced fabrics today.

Jenny Dean, author of the book Wild Colour, has also studied dyes used by the Anglo-Saxons (contemporaries to the Vikings) and has experimented with the colors they yield. All colors I used for the project were rendered in her experiments.

Stitching thread used for sewing the seams is a modern wool/acrylic thread used in tailoring wool suits. I chose this primarily because I wanted something a bit stronger than the more loosely woven threads I purchased for the decorative stitching. It is also stronger and easier to work with than the woolen threads I attempted to unweave from the garment fabric itself to use. Wool, linen or silk thread could have been used in period. (Jones). The chosen thread is, however, 2-ply which was a period-appropriate choice as it was one type of thread used in the Viborg shirt. (Fentz)

The yellow yarn was dyed with weld, which was known in period, but note that yellow during the Viking age could also have come from other sources. The blue yarn was produced with indigo dye, though in period the blue would likely have been achieved with woad (a relative of indigo that grows throughout Scandinavia and the British Isles). (Walton - Dyes)

Stitch types I chose were all present in various archeological finds. I used a running stitch at the edges (which were folded in to prevent fraying) in the weld dyed crewel wool. Had the fabric been more tightly woven or fulled, I would not have had to turn these edges under. (Baker) The joining seam is a butted seam, completed in small overcast stitches placed close together. These seams can be stress points and I prefer them stronger than the stitches I used for the folded edges mentioned above. (Baker)

The small, decorative Xs along the seams were made from the blue crewel wool left from the warp ends of my tablet weaving. Spinning, dyeing and weaving were such labor-intensive endeavors in period that little would be left to waste, even scraps of thread less than a foot long. It stands to reason that they could be used for decorative measures even if they are not long enough for another more practical purpose. Seams are tied off at the ends as was proper for the period.

The hems use a running stitch and are also completed in the weld dyed crewel wool. The top hem, under the trim, is a single fold with running stitch and the bottom hem is a double fold with running stitch. I opted to use a blanket/buttonhole, also used in period, stitch on the straps/loops because I wanted something a bit more decorative. (Baker) And overcast stitch was used to apply the trim.

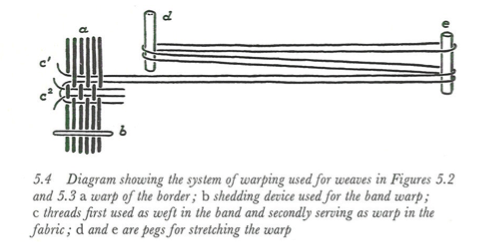

Trim for the dress historically would have been either tablet-woven bands or imported silk samite strips. Both were types of items found in the Oseberg ship burial and at other Norse gravesites. (Christensen and Nockert 383-398; Larsson 182) It is possible that small pieces of tablet-woven bands found near the brooches in graves might actually have been remnants of the tablet weaving used at the beginning of the process of creating fabric on a warp-weighted loom. It is also entirely possible that woven bands were created specifically to decorate the top of an apron dress. Without intact examples, we cannot know if either or both were options. Note that the pattern I used here, as a tablet weaving novice it is the best example of a Scandinavian-style motif (even though I feel the yarn used may have been of an acceptable quality and weight).

Bibliography

Christensen, Arne Emil and Nockert, Margareta. Osebergfunnet: bind iv, Tekstilene (Universitetet i Oslo), 2006.

Fentz, Mytte. "An 11th Century Linen Shirt from Viborg." 1992.

http://forest.gen.nz/Medieval/articles/Viborg/VIBORG.HTM

Geijer, Agnes. Birka III, Die Textilefunde aus Den Grabern. Uppsala,1938.

Hägg, Inga. Die Textilefunde aus der Siedlung und us den Gräbern von Haithabu (Karl Wachlotz Verlag). 1991.

Harte, N.B. and Ponting, K.G. Cloth and Clothing in Medieval Europe, (Heinemann Educational Books), 1984.

Hoffman, Marta. Warp Weighted Loom (Scandinavian University Press), 1975.

Jones, Heather Rose. "Archeological Sewing". 2004. http://heatherrosejones.com/archaeologicalsewing/wool.html

Larsson, Annika. "Viking Age Textiles". The Viking World (Routledge), 2011.

McKenna, Nancy, Chairperson. Medievaltextiles.org.

Simpson, Jacqueline. Everyday Life in the Viking Age (Hippocrene Books), 1967.

Speed, Greg and Walton, Penelope. "A Burial of a VikingWoman at Adwick-le-Street, South Yorkshire". Journal of Medieval Archeology, Volume 48. 2004. 51-90.

Thunem, Hilde. "Viking Women: Aprondress." January 2011. <http://urd.priv.no/viking/smokkr.html>

Walton, P. "Textile Production at 16-22 Coppergate." The Archaeology of York Volume 17: The Small Finds. 1977.

Walton, P. "Dyes of the Viking Age: a summary of recent work." Dyes in History and Archaeology" (Papers Presented at the 7th Annual Meeting, York 1988), 1988. 14-20.

Welander, RDE, Bateyt, Colleen and Cowie, T.G. "A Viking burial from Kneep, Uig, Isle of Lewis," Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot. 1987. 149-174.

Additional Resources

Beatson, Peter and Ferguson, Christobel. "Reconstructing a Viking Hanging Dress from Haithabu." 2008. http://members.ozemail.com.au/~chrisandpeter/hangerock/hangerock.htm

Carlson, Jennifer. "Sewing Stitches Used in Medieval Clothing". 2002. http://www.personal.utulsa.edu/~marc-carlson/cloth/stitches.htm

Dean, Jenny. Wild Color (Potter Craft), 2010.

Graham-Campbell, James. Viking Artefacts (British Museum Publications), 1980.

Hägg, Inga. Die Textilefunde aus dem Hafen von Haithabu (Karl Wachlotz Verlag). 1984.

Hayeur-Smith, Michele. “Dressing the Dead: Gender, Identity, and Adornment in Viking-Age Iceland”, Vinland Revisited, the Norse World at the Turn of the First Millennium, 2003.

Ingstad, Anne Stein. "The Textiles in the Oseberg Ship". http://forest.gen.nz/Medieval/articles/Oseberg/textiles/TEXTILE.HTM

Jesch, Judith. Women in the Viking Age (Boydell Press), 2005.

Jenkins, David. The Cambridge History of Western Textiles (Cambridge University Press), 2003.

Pritchard, Frances. “Aspects of the Wool Textiles from Viking Age Dublin,” Archeological Textiles in Northern Europe (NEASAT 4), 1992.

Priest-Dorman, Carolyn. "Colors, Dyestuffs, and Mordants of the Viking Age: An Introduction." 1999. http://www.cs.vassar.edu/~capriest/vikdyes.html

Skre, Dagfinn. Things from the Town: Artefacts and Inhabitants in Viking-Age Kaupang (Aarhus University Press), 2011.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed