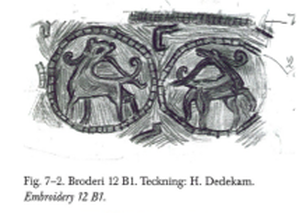

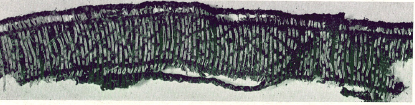

Embroidery as a whole in the Viking Age is exceptionally rare, compared to the thousands of textile finds that we have. Figurative embroidery (rather than just a line of stem stitches, such as that that covers a hem seam at Birka) is even more rare. Of the few samples we do have, some can possibly be attributed to other cultures (such as some of the glorious work from Oseberg being possibly Saxon, Mammen has also been considered as such by some authors, the metal thread embroidery from Valsgarde is thought to either be Byzantine or Slavic, or a copy of the work of those cultures). Even if all of these were native work, the number of these items is minuscule compared to the over all body of textile finds from the period.

It also is smaller than the number of woven patterns in period. (I have started a collection of this evidence here: http://awanderingelf.weebly.com/blog-my-journey/patterned-weaves-preliminary-data ). Tablet weaving itself is rare compared to prior periods, but that too is a type of woven patterning that exceeds the number of embroidery finds.

I have often wondered why this was the case. To a modern person, embroidery is an easier art to adopt (and certainly needs less in the way of space or equipment), but in period weaving was dominant way to decorate textiles. I have seen it argued that this was not a culture of linear art (they were not taught to draw from a young age as we were), and that makes sense. I also wonder if there was something symbolic in it (we know that many ancient cultures have textile arts playing a prominent role in their mythology), or perhaps ritual.

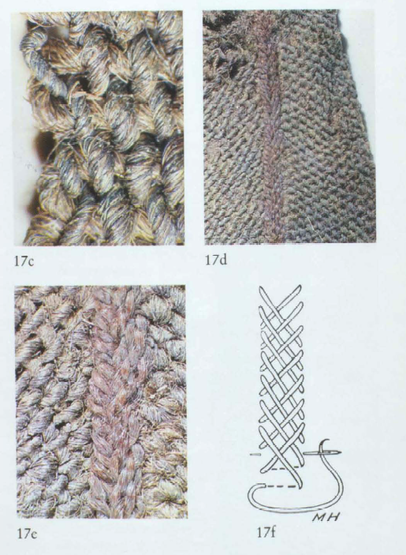

As I read more about other cultures, times and areas, I see that this lack of embroidery in Northern Europe is reflected elsewhere as well. Johanna Banck-Burgess notes the same phenomena in Central Europe in early Celtic works as well (this shows up in both her work on the Hochdorf burial and in the article "Prehistoric textile patterns: transfer with obstruction"). There we have various types of patterned weaving that are a result of manipulation of the web on the loom (whether it be by the turn of cards in tablet weaving, or supplemental threads used in soumak-like techniques or insertion of metal rings into the the weave of the cloth). Embroidery is completely absent in some areas in early Celtic cultures, and very rare in others.

And you know what? It does not stop there. In the article, "Unravelling the Tangled Threads of Ancient Embroidery" by Kerstin Droß-Krüpe and Annette Paetz, the idea that mistranslation might play a role in perceptions of profuse embroidery in the ancient world. I found this rather riveting to read because it very much parallels the conclusions I have come to about later textiles as well, that the number of embroidered items are very low compared to textiles that are either undecorated or decorated by means of weaving.

And of course, now I want to know the why of this even more.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed