Celtic finds, Migration Period, Viking Age... so many periods were the beads seem to be valued for their uniqueness, rather than "matching" in a mirroring sort of way. In some collections we see a possibility for balance in the stringing (we often do not know exactly how they were strung during life, and many reconstructions opt for at least balance in the overall look if exact symmetry is not possible), but not that mirroring effect.

I know that my first Viking strands were always painfully symmetrical, and they never really looked "right" to me. I was definitely over engineering. I am happier with the things that I make now, where I let different beads speak to me and get included for what each one brings to my mind.

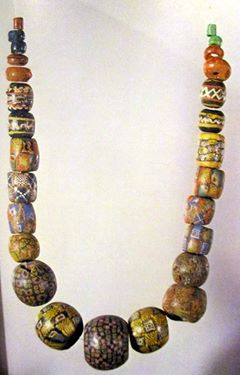

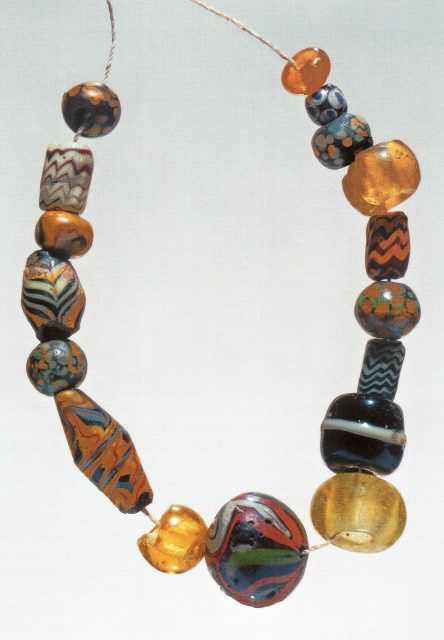

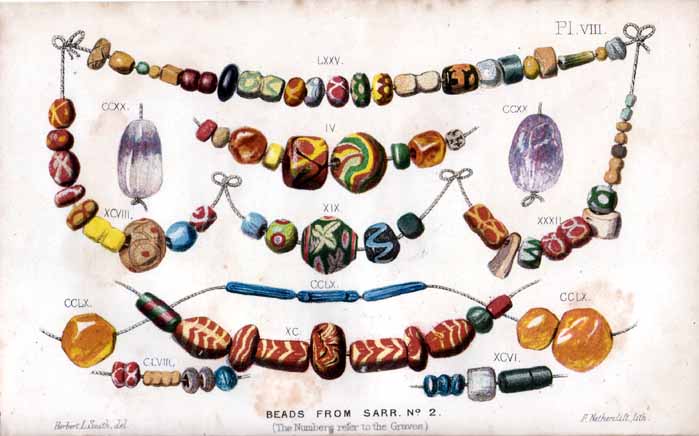

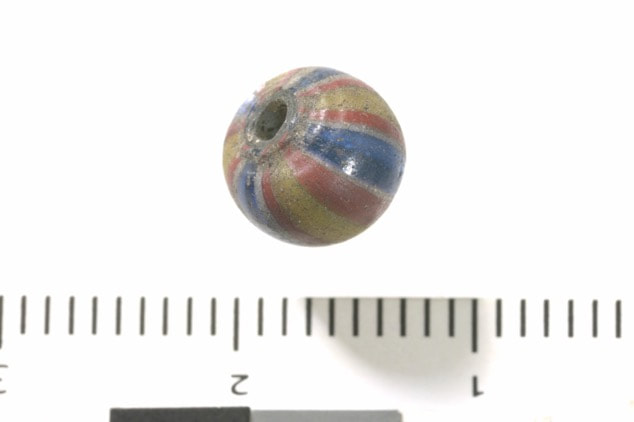

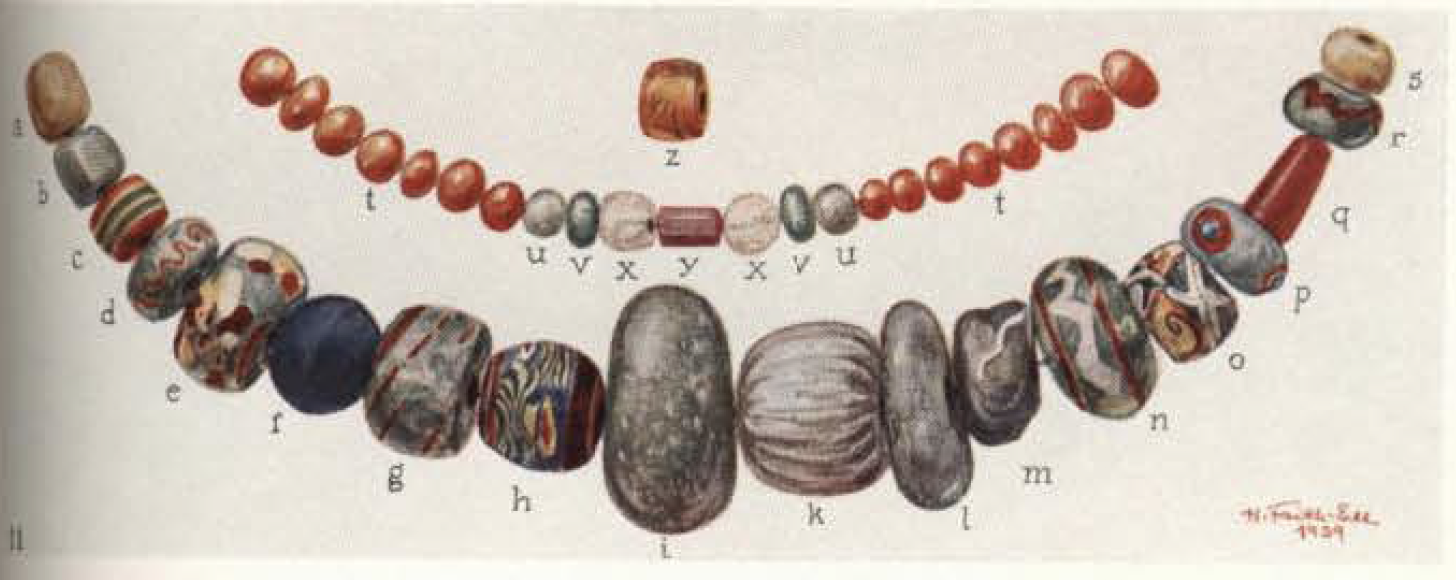

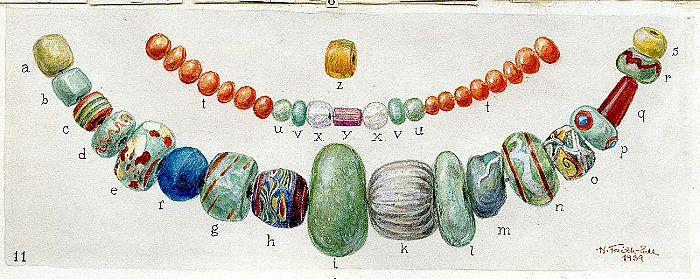

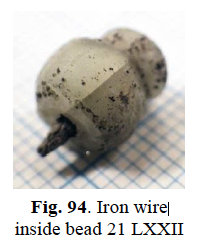

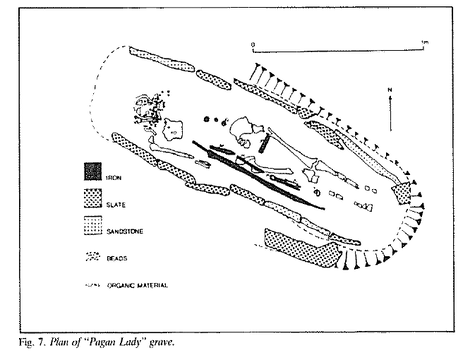

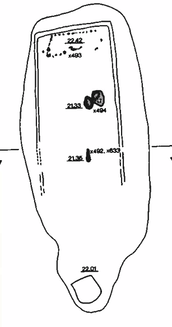

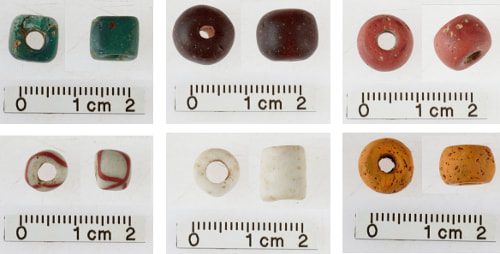

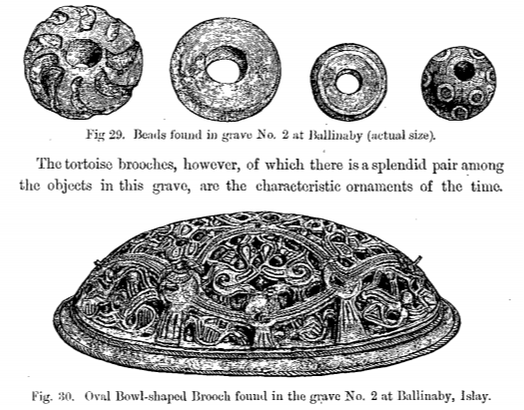

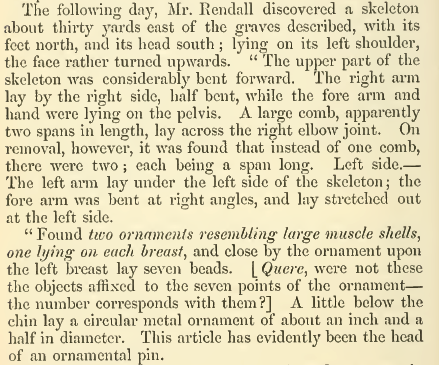

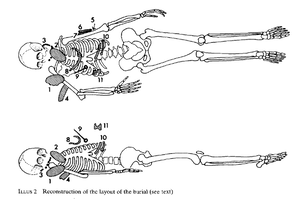

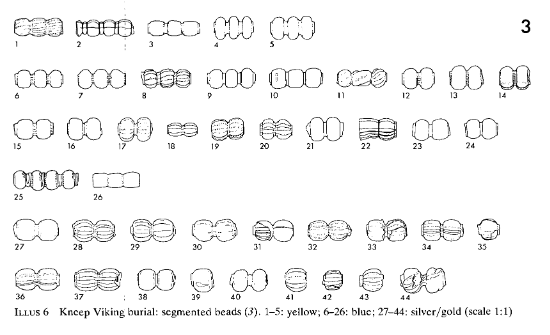

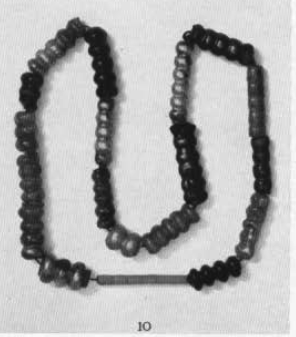

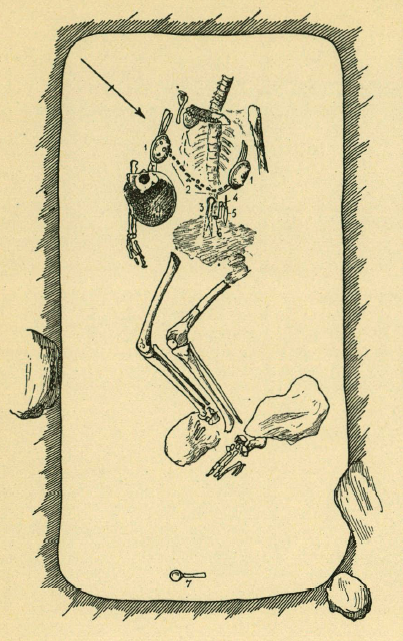

Below are some examples of extant groupings of beads that show off balance (with out absolute symmetry) and and some collections that really are a delightfully chaotic mix of things that seem to speak more to me of the people and places from which these items came.

Many museums have beads online and its sometimes worth it to just spend hours surfing until inspiration hits (unimus.no, National Museum of Denmark, Saxon beads are also easy to track down... heck, this is the one time I am actually going to recommend surfing the hated Pinterest for inspiration).

Honestly? I would LOVE to see more of this type of work, these things that make the piece unique, in the modern world as well.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed