Archaeology shows that during the latter part of the 10th Century the necessary brooches for the garment appear less frequently in graves and they eventually disappear by the end of the 11th century across Scandinavia. (Hägg, Textilien un Tracht, 320-321). In Denmark the brooches fall out of favor as early as 900CE in some areas. (Eisenschmidt, 100) This could be, in part, due to adoption of Christianity, and with it a more continental style of costume. The new style of costume could have been due to foreign fashions becoming a status symbol among the elite and wealthy in Scandinavia.

The first evidence of shift in costume is seen in Denmark, particularly in trade centers such as Hedeby. Denmark shared a border with the Carolingian Empire and trade between the two locations was common. Eventually, foreign items became status symbols in Scandinavia. Examples of this include items such as Frankish belt mounts (items that later morphed into their own form of trefoil brooch), and goods such as leather pouches and belts that were possessed by the elite of society. (Krag, Oriental Influences, 113-114) There was even foreign influence on dress beyond accessories and ornament. The caftan is a an example of such an item as it was thought to have either been in imitation of high rank foreign dress, or that the garments were received as gifts from foreign officials. (Hägg, Textilien un Tracht, 327; Krag, Christian Influences, 239-241; Geijer, Textile finds, 95-96; Andersson, Birka, 39-40).

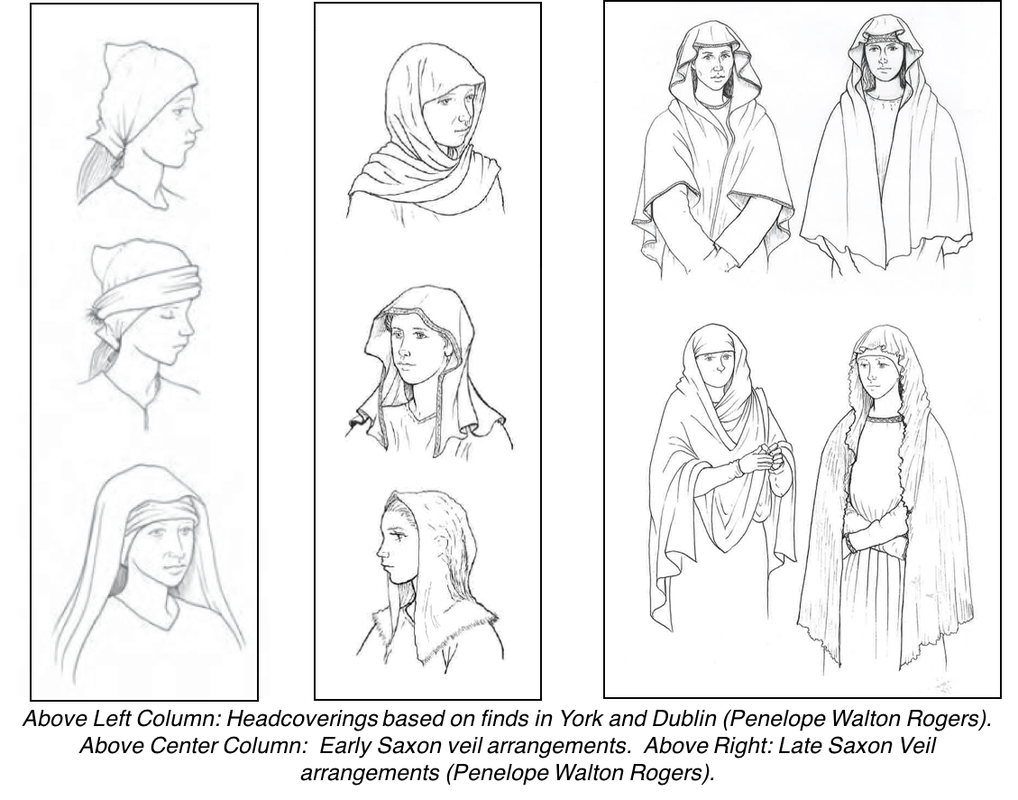

Another garment that likely has ties to both status and conversion could be women’s headcoverings. Very fine wool and silk tabbies, as well as an impression of open weave linen, have been found in numerous graves, particularly those of women, from the Viking Age and beyond. Frequently this cloth is interpreted as veils or caps because of their similarity with the existing identifiable headcoverings from Dublin, Lincoln and York. The 10th Century grave from Hørning had such a fine wool mantle affixed to a wide tablet woven band that appeared to have been draped across the head and down along the body in the manner of a Frankish, Byzantine or Roman dress (Krag, Denmark, 29-34)

Additional places where a shift in costume likely happened earlier were certain settlements in the British Isles, where it is thought that in many locations the Norse style of dress was abandoned within a mere generation or two, or that the settlers were from Denmark (where fashion had already changed) rather than Norway or Sweden. (Kershaw, 225-227)

Is Transitional Dress for You?

- Gifting was a common practice of the period, with foreign officials gifting to the high status Norse men in their military. Likewise, Norse chieftains would have gifted to their own high ranking men to keep their alliance.

Would you be considered high status or wealthy?

- It is possibly that some high status individuals would take on new fashions before others.

Do you live in an urban area/trade center rather than rurally?

- Urban and trade centers had more access to the most desirable goods, as well as more news of what was happening elsewhere.

Do you live in a region that has already converted to Christianity?

- While these garments are not limited to Christians, it might be more likely that you adopt what could have initially perceived as Christian dress at the time, before it became ”fashion” for others.

Does your chosen region and time show a decline in oval brooches as grave goods?

- Denmark, for example, had oval brooches disappear from graves earlier than other sites.

- Some parts of Great Britain showed a decline in specific Norse dress styles after only a couple of generations.

How Would Transitional Dress Look

In this example of such possible fashion, this woman wears a gown of fine wool twill or tabby, dyed blue (well-dyed cloth would be a status symbol). Her sleeves are of an exaggerated length and pushed back up onto the forearm. Because she has the means, they are held there with bracelets or silk cloth cuffs could have been an option.

The dress itself could possibly have some tailoring as that practice started before this style arose amongst the Norse, but is not a closely fitted garment.

The outer gown is worn over a linen dress, closed at the throat with a small brooch. She wears a necklace of colorful glass beads and metal pendants. While round pendants are used here, a cross would also be a an option.

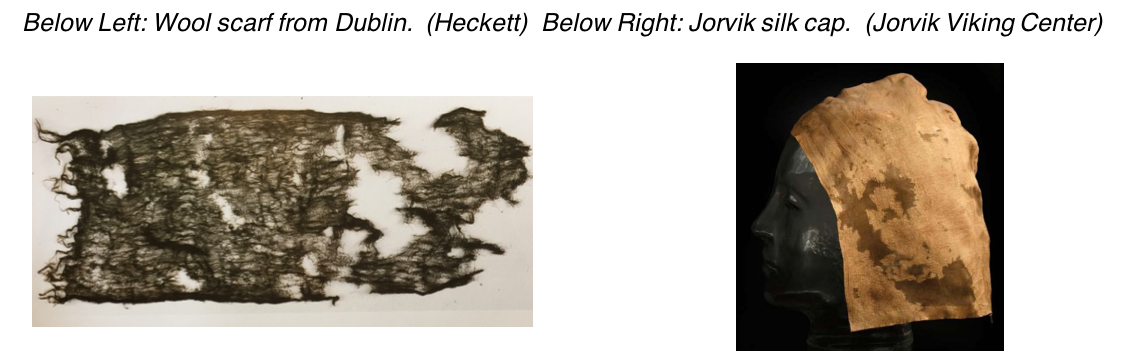

Her headcovering consists of a small cap or cloth (similar to those from Dublin) covered with a veil. This would likely be fine, open weave wool, though linen or silk are also possibilities. The veil itself might be edged with a fine, brocaded tablet woven band.

The length of dress and the long sleeves, as well as the dyed cloth and other jewelry show her status. A woman with less wealth might have a slightly shorter gown, sleeves that reach the wrist only, less or no jewelry and undyed cloth (from a naturally pigmented sheep’s wool).

Layers

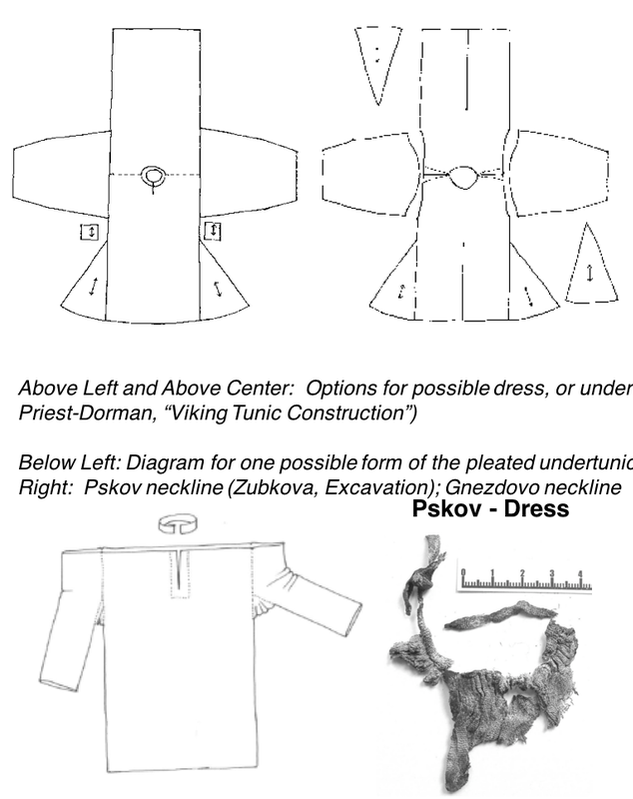

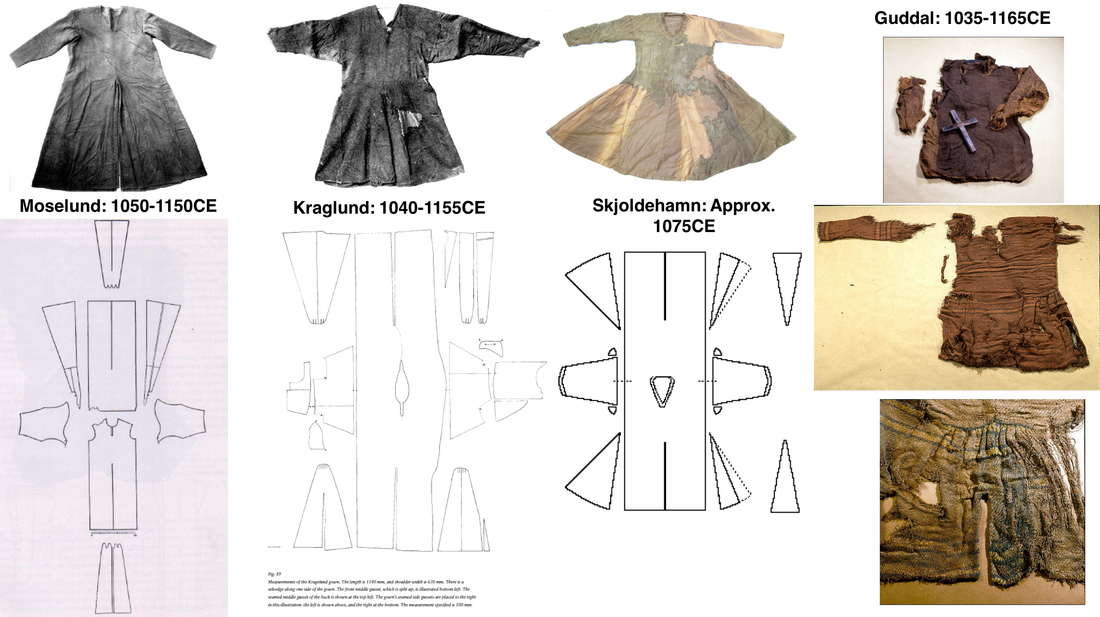

During the late Viking age this linen garment might have been a Slavic import (Hägg, Textilien, p325) and might also have been finely pleated into a neckline such as seen in examples from Birka and Hedeby.

This dress could also be worn in layers over an undertunic. A wealthy woman with connections might also have had silk trim on her gown, or have had cloth that was well dyed.

It is also possible that cloth belts without metal fittings were worn, such as a cloth girdle or sash as could be found in other areas of the world during the Viking Age. As the aprondress was falling from fashion, and other styles of dress were adopted belts might have become more common. For example, after the Migration Era (7th century and onward), it seems that Saxon women were shifting towards styles with a Mediterranean influence and these included woven belts, including possibly tablet weaving or open, net-like cloth sashes with fringed ends. (Walton Rogers, Cloth and Clothing, 220-221). A belt is even specifically mentioned in the poem “The Baptism of King Harald” which occurred in 826AD. Here the Danish King and his wife’s newly adopted attire for the ceremony is described. She wears a gold-brocade silk costume, a gold-wrought veil, belt and bracelet. (Krag, Christian Influences, 241). There are also images of women, from these areas of influence (Saxon and Byzantine), that seem to show a belt as part of the costume.

Remember too that just as with earlier Viking costume, that wearing no belt at all is an option.

Mantles/Cloaks: Metal figures and the Oseberg tapestry, as well as archaeological finds, show women wore some sort of layer over their tunics and gowns. Both cloaks and coats as part of Norse dress have been suggested by various experts.

As time progresses cloaks or mantles seem to be more common in depictions from other cultures (such as Byzantine or Saxon). A cloak or mantle could be pinned in the center front. Rectangular or square cloaks would be optimal with half-circle being a possible very high status option.

Headdresses: Metal icons from the Viking Age show women with their hair left uncovered in elaborate braids. These figures also seem to depict high status dress, and it is possible that uncovered hair might have been for festivals during that time period. However, there are also theories that those icons might not have represented human women or dress at all and that too should be considered here.

With the waning of the Viking Age came Christianity, and with that new religion arrived the concept of covering ones hair for modesty. While it is often said that pagan Norse women “always” wore their hair uncovered and Christian women “always” covered their hair, the evidence does not make such a clear delineation. There can be very practical reasons (beyond fashion) for covering ones hair, especially where working in the sun or around smoky fires.

The largest collection of extant women’s head coverings comes from Dublin. These finds, dated 10th-12th century, are of either silk or very fine, gauzy wool, have small scarves, caps and veils. There are a number of ways to wear these items, including using the scarves and caps as a base for a veil, which corresponds to well to some head dress styles from Europe during the same time period. Linen, while not found as a headcovering at the sites, might also have been a possibility.

The caps that have been found are universally narrow with the final width measuring between 15-18cm wide. Half of the extant items show signs of having a dart stitched into the back (allowing it to conform to the head), some of these had the excess fabric still visible on the outside of the cap forming a peak. Some caps were also sewn down the back, while others were open (possibly to accommodate a bun?). There are also several narrow scarves, some with fringed ends, and some even narrower cloth bands. Many of these items have been dyed. All of this points to variety in possible headcovering styles.

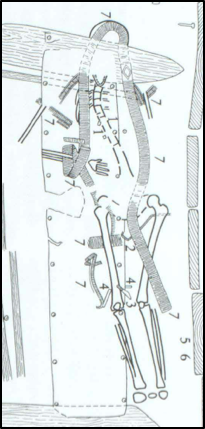

| The extant headdresses might not have been worn singly. It is possible they formed part of a layered headcovering, with caps and/or scarves forming a base for a veil, especially as later in the Viking Age and moving towards the Middle Ages. Sometimes veils could be edged with metal brocade tablet weaving (a sign of very high status that can be seen in the woman’s grave at Hørning and Fyrkat). Left: Diagram of the woman’s grave at Hørning. This was a very high status burial that had a wide band of gold brocade tablet weaving that might have edged a veil or mantle. (Voss, 194) |

My Own Interpretation

I am using layered headcoverings based on those from Dublin (though in my photo here, my wool veil is slipping off the back due to my taking it off to use as a class example and not having a mirror when I replaced it). For my photo I am wearing a leather belt, because I have not yet crafted one for myself that is textile based.

This garment is in linen and was to test the construction of my Hedeby/Moselund patterning. The next iteration will be in fine, dark blue wool twill with silk trim. I also have dyed a fine wool mantle/veil that fits with graves such as that from Hørning and Fyrkat. While my look represents a woman of high status, and has elements, such as the veil, that fits with Christian ideals, she is not necessarily a convert herself (as there are thoughts that graves such as Fyrkat might have been to a volva). I look forward to working further with these concepts, patterns and the over all look.

References & Resources

Andersson, Eva. Tools for Textile Production from Birka and Hedeby (The Birka Project for Riksantikvarieambetet), 2003.

Andersson Strand, Eva. ”An Exceptional Woman from Birka”, A Stitch in Time: Essays in Honour of Lise Bender Jørgensen (Gothenberg University), 2014.

Bender Jørgensen, Lise. Northern European Textiles until AD 1000, Aarhus University Press), 1992

Bender Jørgensen, Lise. Prehistoric Scandinavian Textiles, (Det Kongelige Nordiske oldskriftselskab), 1986.

Blindheim, Charlotte, “Drakt og smykker”, Viking 11.

Christensen, Arne Emil and Nockert, Margareta. Osebergfunnet: bind iv, Tekstilene (Universitetet i Oslo), 2006.

Fetz, Mytte. “An 11th Century Linen Shirt from Viborg Søndersø, Denmark”, Archaeological Textiles in Northern Europe: Report from the 4th NESAT Symposium 1.-.5 May 1990, NESAT 4 (Copenhagen), 1992.

Fransen, Lili, Shelly Nordtorp-Madson, Anna Norgard, and Else Østergård. Medieval Garments Reconstructed: Norse Clothing Patterns (Aarhaus University Press), 2010.

Geijer, Agnes. Birka III, Die Textilefunde aus Den Grabern. Uppsala,1938.

Geijer, Agnes. “The Textile Finds from Birka,” Cloth and Clothing in Medieval Europe (Heinemann Educational Books), 1984.

Gråslund, Anne Sofie. “Late Viking Age Christian Identity”, Shetland and the Viking World, Papers from the Seventeenth Viking Congress (Lerwick), 2016.

Hägg, Inga. Die Textilefunde aus der Siedlung und us den Gräbern von Haithabu (Karl Wachlotz Verlag). 1991.

Hägg, Inga. Die Textilefunde aus dem Hafen von Haithabu (Karl Wachlotz Verlag). 1984.

Hägg, Inga, “Kvinnodräkten i Birka: Livplaggens rekonstruktion på grundval av det arkeologiska materialet”, Uppsala: Archaeological Institute, 1974

Hägg, Inga. “Viking Womens Dress at Birka,” Cloth and Clothing in Medieval Europe (Heinemann Educational Books), 1984.

Hägg, Inga. Textilien und Tracht in Haithabu and Schleswif (Wachholtz Murmann Publishhers), 2015.

Harrison, Stephen H. “Viking Graves and Grave Goods in Ireland”, The Vikings in Ireland (Roskilde), 2001.

Hedeager Krag, Anne. “Reconstruction of a Viking Magnate Dress”, Archäologische Textilfunde - Archaeological Textiles: Textilsymposium Neunmünster 4.-7.5, 1993, NESAT 5. 1994.

Hedeager Krag, Anne. “Denmark - Europe: Dress and Fashion in Denmark's Viking Age”, Northern Archaeological Textiles; Textile Symposium in Edinburgh, 5th-7th May 1999, NESAT 7 (Oxbow Books), 2005.

Hedeager Krag, Anne. “Oriental Influences in The Danish Viking Age: Kaftan and Belt with Pouch”, North European Symposium for Archaeological Textiles X, Oxbow Books, Ancient Textiles Series Vol. 5, 2009.

Hedeager Krag, Anne. “Finely Woven textiles from the Danish Viking Age”, NESAT IX, Archäologische Textilfunde - Archaeological Textiles, 2007.

Hedeager Krag, Anne. “Dress and Power in Prehistoric Scandinavia c. 550-1050A.D.”, Textiles in European Archaeology: Report from the 6th NESAT Symposium, 7-11th May 1996 in Borås (Göteborg University), 1998.

Hedeager Krag, Anne. “Finely Woven Textiles from the Danish Viking Age”,

Hedeager Krag, Anne. “New Light on a Viking Garment from Ladby, Denmark”, Acta Archaeologica Lodziensla Nr 50/1: Priceless Invention of Humanity – Textiles, NESAT 8, 2004.

Hedeager Krag, Anne. “Christian Influences and Symbols of Power in Textiles from Viking Age Denmark. Christian Influence from the Continent”, Ancient Textiles: Production, Craft and Society (Oxbow Books), 2008.

Hedeager Madsen, Anne. “Women's Dress in the Viking Period in Denmark, Based on Tortoise Brooches and Textile Remains”, Textiles in Northern Archaeology; NESAT Textile Symposium in York 6-9 May 1987, NESAT 3 (Archetype Publications), 1990.

Heckett, Elizabeth Wincott. Viking Age Headcoverings from Dublin (Royal Irish Academy), 2003.

Heckett, Elizabeth Wincott. “Medieval Textiles from Waterford City”, Archäologische Textilfunde - Archaeological Textiles: Textilsymposium Neunmünster 4.-7.5, 1993, NESAT 5. 1994.

Helle, Knut. Cambridge History of Scandinavia, Volume 1 (Cambridge University Press), 2003.

Henry, Philippa A. Textiles as Indices of Late Saxon Social Dynamics”, Textiles in European Archaeology: Report from the 6th NESAT Symposium, 7-11th May 1996 in Borås (Göteborg University), 1998.

Henry, Philippa A. “Who Produced Textiles? Changing Gender Roles in Late Saxon Textile Production: the Archaeological and Documentary Evidence”, Northern Archaeological Textiles; Textile Symposium in Edinburgh, 5th-7th May 1999, NESAT 7 (Oxbow Books), 2005.

Jenkins, David. The Cambridge History of Western Textiles (Cambridge University Press), 2003.

Kjellberg, Anne. “Medieval Textiles from the Excavations in the Old Town of Oslo”, Textilsymposium Neumünster: Archäologische Textilfunde (NESAT 1), 1981.

Kershaw, Jennifer. Viking Identities: Scandinavian Jewelry in England (Oxford University Press), 2013.

Krag, Anne Hedeager and Lise Ræder Knudsen:

Vikingetidstekstiler. Nye opdagelser fra gravfundene i Hvilehøj og Hørning. Nationalmuseets Arbejdsmark. København 1999, 159-170. (in Danish with english summary)

Lee, Christina. “Viking Age Women”, In Search of Vikings: Interdisciplinary Approaches to the Scandinavian Heritage of North-West England (CRC Press), 2014.

Lindström, Märta. “Medieval Textiles Finds in Lund”, Textilsymposium Neumünster: Archäologische Textilfunde (NESAT 1), 1981.

Nordeide, Sæbjorg Walaker. “Urbanism and Christianity in Norway”, The Viking Age: Ireland and the West (Four Courts Press), 2010.

Norstein, Frida Espolin. “Migration and the creation of identity in the Viking diaspora: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF VIKING AGE FUNERARY RITES FROM NORTHERN SCOTLAND AND MØRE OG ROMSDAL”, University of Oslo, 2014.

Ostergaard, Else. Woven into the Earth: Textile finds in Norse Greenland (Aarhus University Press), 2004.

Owen-Crocker, Gale R. Dress in Anglo-Saxon England (Boydell Press), 2010.

Pritchard, F. “Aspects of the Wool Textiles from Viking Age Dublin.” Archaeological Textiles in Northern Europe: Report from the 4th NESAT Symposium 1.-.5 May 1990, NESAT 4, 1992.

Pritchard, F. ”Textiles from Recent Excavations in the City of London Introduction”, Textilsymposium Neumünster: Archäologische Textilfunde (NESAT 1), 1981.

Pritchard, F. “Silk Braids and Textiles of the Viking Age from Dublin”, Archaeological Textiles: Report from the 2nd NESAT Sumposium (København Universitet), 1998.

Roesdahl, Else. Fyrkat en jysk Vikingenborg – II. Oldsagerne og gravepladsen (National Museum of Denmark), 1977.

Simpson, Jacqueline. Everyday Life in the Viking Age (Hippocrene Books), 1967.

Skogland, G., M. Nockert and B. Holst. “Viking and Early Middle Ages Northern Scandinavian Textiles Proven to be Made with Hemp,” Nature, 2013.

Sorheim, Helge, ‘Three Prominent Norwegian Ladies with British Connections’, Acta Archaeologica, 82 (2011)

Speed, Greg and Walton, Penelope. "A Burial of a VikingWoman at Adwick-le-Street, South Yorkshire". Journal of Medieval Archeology, Volume 48. 2004. 51-90.

Thunem, Hilde. "Viking Women: Underdress." 2014. http://urd.priv.no/viking/serk.html

“Universitetsmuseenes Fotoportal,” 2013. http://www.unimus.no/foto/

Voss, Olfert. “Høning-graven: En kammergrav fra o. 1000 med kvinde begravet I vognfading”, Mammen: Grave, kunst og samfund I vikingetid (Jusk Arkaeologisk Selskab), 1991.

Walton Rogers, P. "Textiles, Cordage and Raw Fiber from 16-22 Coppergate,” The Archaeology of York Volume 17: The Small Finds. 1989.

Walton Rogers, P. "Textile Production at 16-22 Coppergate." The Archaeology of York Volume 17: The Small Finds. 1997.

Walton Rogers, Penelope. “The Textiles,” Archaeology of York (28-29 High Ousegate), Web Series, No. 3.

Walton Rogers, Penelope. Cloth and Clothing in Early Anglo-Saxon England (Council for British Archaeology), 2007.

Walton Rogers, Penelope. “Cloth, Clothing and Anglo-Saxon Woman”, A Stitch in Time: Essays in Honour of Lise Bender Jørgensen (Gothenberg University), 2014.

Winroth, Anders. The Conversion of Scandinavia (Yale University Press), 2014.

Zubkova, E.S, Orinskaya, O.V, and Mikhailov, K.A. “Studies of the Textiles from the Excavation of Pskov in 2006,” NESAT X, 2009.

Zubkova, E.S, Orinskaya, O.V., and Likhachev, D. “New Discovery of Viking Age Clothing from Pskon, Russia.” (Notes and summary by Perer Beatson) http://members.ozemail.com.au/~chrisandpeter/sarafan/sarafan.htm

RSS Feed

RSS Feed