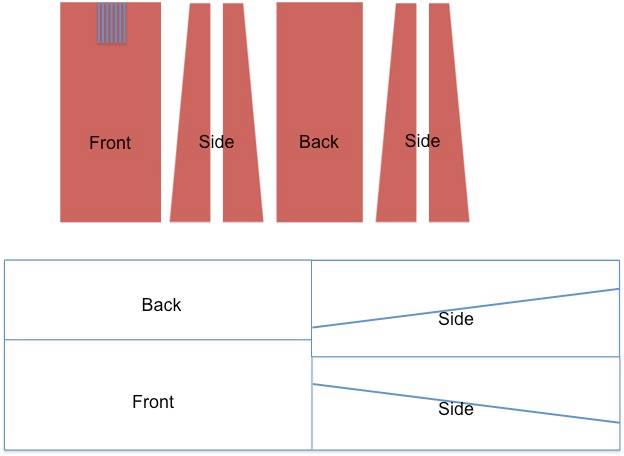

This version was made from lightweight linen, with the idea of being able to wear the garments layered even in warmer weather. The cutting layout I chose was quite simple and produced a garment that has plenty of room for movement, while not giving too much volume to the hemline. I added a bit of tailoring to the top of the side gores, but this is sill a loose, comfortable garment. After making my dress, and wearing it, I realized there is s something exceptionally simple and functional about these pleated garments. Pleats would be the absolute simplest manner of taking in a dress that is now too large, or letting out one in which you might need more room.

Before crafting my pleats I did some experimentation to get the size of the pleats correct. Even though my dress is linen, I did experiment as well with wool. I also did some research on my own on the extant pleated smokkrs from Kaupang, Kostrup and Vangsnes.

The dress at Kaupang had pleats that were 4-5mm deep and was made from fine broken diamond twill (approx 88 threads per inch in the warp and 38 in the weft). This textile is highly fragmented.

Vangsnes B5265 has a larger fragment of pleated fabric as can be seen in the image below. This was a wool tabby that had pleats 2-3mm deep.

Kostrup has the most compelling fragments and Hilde Thunem has the best images of those here: http://urd.priv.no/viking/kostrup.html That garment, like Vangsnes, was also a wool tabby. The thread count is approximately 66 threads per inch in the warp and 25 in the weft. The pleats there, according to Hilde Thunem, are 2-3 mm deep and 3 mm wide. There is not enough left of the fabric to let us know how far down the pleats ran.

AnoThe Problem with Pleats

None of these dresses give much in the way of clues about how the pleats were crafted or secured. Things we do know are:

- There is no evidence of thread or stitching holding the pleats.

- There is no evidence of any sort of band sewn to the top or back of the pleats to let them keep their shape.

- There is lack of noticeable wear on the pleats and the fabric still has visible weave and texture.

- Two of the pleated fragments are hemmed at the top before pleating.

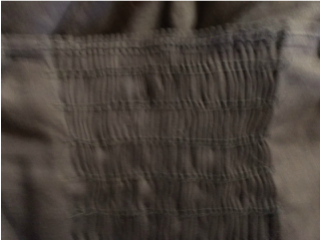

- The pleats are very narrow (2-5mm across all three samples). Kostrup and Vangsnes are clearly stacked closely together and do not appear to lay flat.

Using Thread to Draw the Pleats

One theory, suggested by Rasmussen and Lønborg is that a linen thread was used to draw up and secure the pleats. While no thread remains, linen might well have degraded in the grave leaving little or no trace. Further, if indeed the garment was made in this manner it makes sense that a thread used for that purpose be of linen, rather than wool as wool would try to stick to itself and would catch making it difficult to form the pleats. Linen, especially if waxed, glides though wool fabric easily.

The problem I have with this is after experimenting with this is that those pleats have a tendency to shift along the string with wear (unless they are very compact to begin with). It is also very easy to break the the pleating thread or create a small pull or hole in the ground fabric. However, it would be a fairly quick way to make the pleats and to secure them.

Steaming the Pleats

Quite a few people in online forums have have suggested that the pleats were set by steaming, causing the wool fabric to felt, thereby holding the pleats. While steam can definitely be used to help set a pleat, it would not felt a textile to an extent that it would hold the shape of the pleats during wear at the edge of a garment (not and still have the individual threads in the weave still be plainly visible).

What do I mean by this? If you make a wool skirt, create pleats and set them into a waistband and then steam it, those pleats will last some time. However, without the waistband there, they will absolutely not hold shape to the waist, or in the case of an aprondress, hold shape at the bust. The only way to get the pleats to maintain that shape would be to take the felting process much further than the evidence shows us as you can still see the weave in the cloth on these finds. Even if one thought the garment was felted, I do not think there is enough felting to maintain shape without some other form of structural support.

Another option for steaming would be a more loose garment. However, over time the weight of the wool itself would pull the pleats open, possibly in a sagging U shape to some extent.

Weaving/Steaming the Pleats

Another, more recent theory, suggested by Nille Glaesel is that the pleated portion of the dress is created on the loom. The idea is that while weaving the dress fabric an additional linen weft is inserted periodically and then drawn together after weaving to create the pleats. The textile is then steamed to set the the pleats and the strings are removed. The problem with this is the same as I mentioned above. The pleats are still not capable of holding shape at the bust. Nille had to add a band to secure hers. (Further, as a weaver, I find this far more tedious of a process than simply drawing the pleats on a thread after the garment is crafted.)

Bands at the Top or Behind

I see no clear evidence of a band sewn to the top of the garment, or even from the back, to keep the pleats from stretching open with wear though Nille Glaesel believes that blue linen found in the grave served that purpose. My issue with this theory is that the reasoning behind weaving the pleats in to begin with is that there were no threads or holes left from a drawing thread or stabilizing thread. Yet an assumption is being made that all of the threads holding this band on have since disappeared.

Stabilizing Stitch

While there is no more evidence of this stitch than of the drawing thread, this is a practical solution that, to me, is at least plausible. A careful seamstress could sew in the drawing thread without piercing the yarn of the textile (or, at least, without often doing it). Likewise, Stitches added from behind could penetrate the web of the textile, without impaling individual weaving threads. While I think it unlikely that all of this linen yarn would disappear in the grave, I find it far more likely than there being an entire band, plus its stitching, that disintegrated over time.

This is the solution I ended up using (and it is the same conclusion that others have come to as well). We do not have the evidence to say that it was definitively done in this manner, but I feel that it is still more than plausible (and more plausible than some other possible solutions).

I chose to use a method similar to that used on later Norwegian clothing where the pleats are drawn up on a thread, and whip stitched in place.

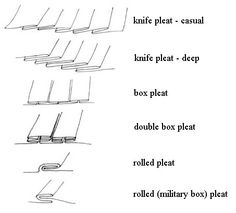

| What About Other Types of Pleats This one is touchy. I have seem beautiful versions of these pleated smokkrs that involve knife or box pleats. Frequently these pleats are stitched down with long rows of stitching that run vertically on the pleat. Occasionally, these pleats are used to create additional tailoring in the garment. All of these pleats lay flat, and are typically also encased in bands of some sort. |

I have to think that sometimes modern ideals guide these choices. I know that there was a time that I never would have worn a pleated front dress (which looks to me very much like a maternity gown), preferring instead garments that were more tailored and flattering to a modern eye.

Another reason that might prompt these choices is the wrong choice of fabric (and sometimes, this is unavoidable, as the right wools are frequently difficult to obtain). The thread counts in the extant garments are very high. These were fine wool textiles. What we often buy as reenactors are much more coarse, and often our cloth also often has a brushed surface. Thick fulled fabric will produce very bulky pleats that would appear quite off if they could even form a small enough pleat at all. The bulk produced by these textiles can be very off-putting to many. The fabrics to sometimes tend to conform nicely as deep, flat pleats, and that might be the reasoning behind some choices.

I plan to make another pleated dress out of a mid-weight linen for Pennsic and then eventually a wool one. I enjoy the dress I made more than I thought I would and hope to explore additional possibilities for both the pleating and over all construction of the dress with each iteration.

Blindheim, Charlotte. Kaupang-funnene, bind II, (University of Oslo), 1999.

Glaesel, Nille. "The Kostrup Aprondress", 2015.

Holm-Olsen, Inger Marie. “Noen gravfunn fra Vestlandet som kaster lys over vikingtidens kvinnedrakt”, Viking, 39, 1976.

Ingstad, Anne Stein. “Two Women’s Graves with Textiles from Kaupang,” Universitetets Oldsaksamling 150 år, Jubileumsårbok, 1979

Rasmussen, Liisa and Lønborg, Bjarne. Dragtrester i grav ACQ, Køstrup, 1993.

Thunem, Hilde. "Viking Women: Aprondress." January 2011. http://urd.priv.no/viking/smokkr.html

Thunem, Hilde. "The aprondress from Kostrup (grave ACQ)." April 2015. http://urd.priv.no/viking/kostrup.html

Vedeler, Marianne, ‘Pleated Fragments of Clothing from Norway’, NESAT VIII, 1997.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed