Last year I decided I wanted to come up with a super easy, one layer sort of loose garment that I could do in linen that is more period than my typical bog dresses. (My "bog dress" is a modified version of the typical two-flap style that involves less fabric, less bunching, and some pleats for better drape. It is plausible, but is "inspired by" rather than based on an actual extant piece. My instructions are here: http://awanderingelf.weebly.com/blog-my-journey/sca-standards-the-bog-dress) awanderingelf.weebly.com/blog-my-journey/sca-standards-the-bog-dress

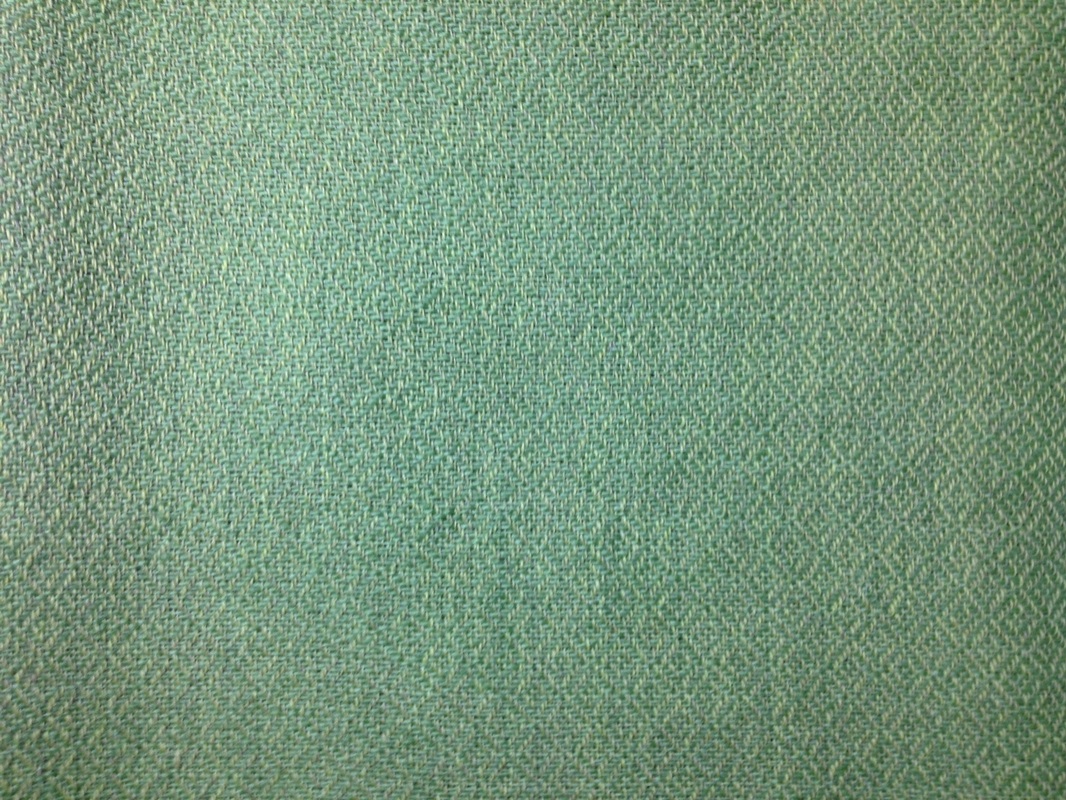

I prefer linen at War, but the issue with linen is that its drape does not lend well to garments that have a lot of fabric bunched up at the waist. Linen has a very beautiful crisp hand, and tends to fall away from the body rather than flow over it. Linen is also typically a tabby weave. Tabby also tends to fall away from the body, whereas a twill will better flow.

I recalled awhile ago that I was deciding on what to do with some lovely mid-weight wool, twill plaid, and tested a very hypothetical garment out in that cloth. The bulk was too much, but just maybe it would work with this mid-weight linen...

The Garment

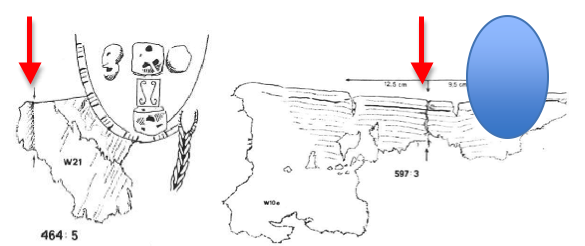

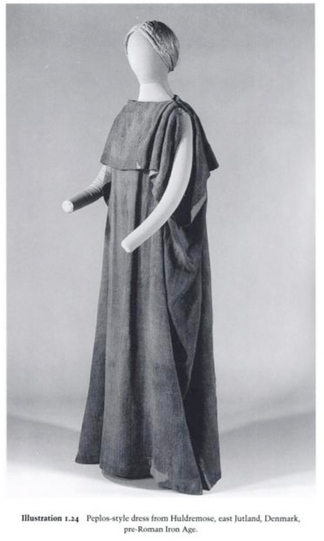

Photo credit to H. Momen, from the article Visions of Dress.

Photo credit to H. Momen, from the article Visions of Dress. In my massive stash of books and articles I have one entitled "Visions of Dress. Recreating Bronze Age Clothing from the Danube Region". This is by Karina Grömer, Lise Bender Jørgensen and Helga Rösel-Mautendorfer. I tend to collect articles by certain authors, in this case it was Bender Jørgensen that is responsible for this one being in my stash. It discusses a fantastic find from the Bronze Age in Austria and what the plausible costume construction for the fantastic (and dangerous, lol) jewelry could have been.

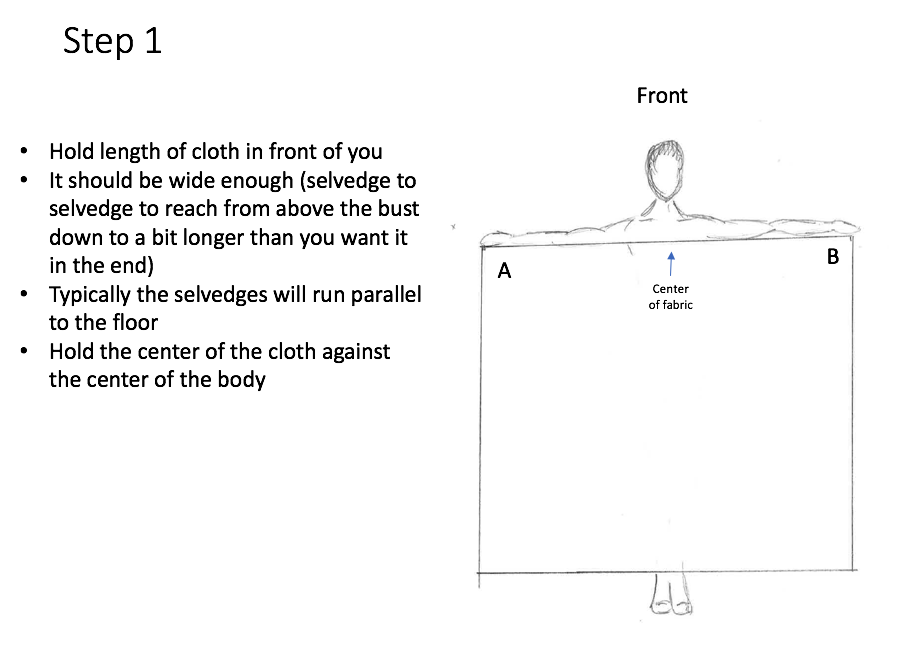

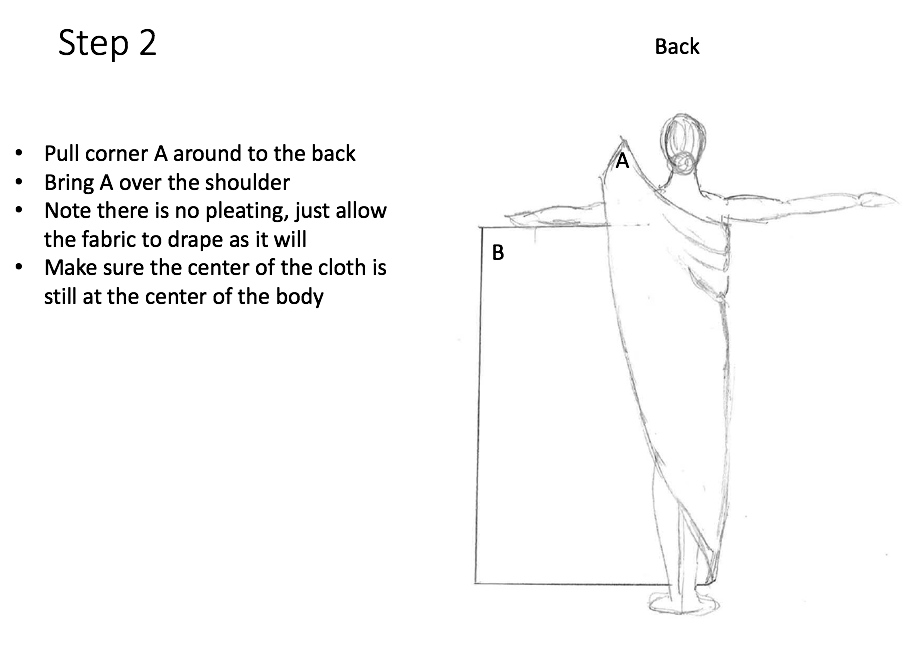

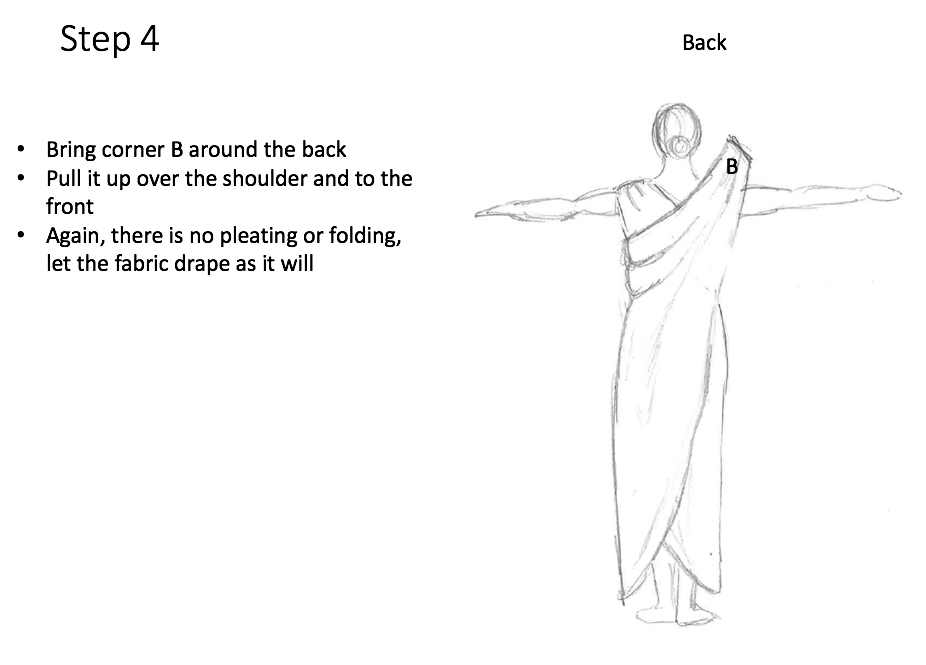

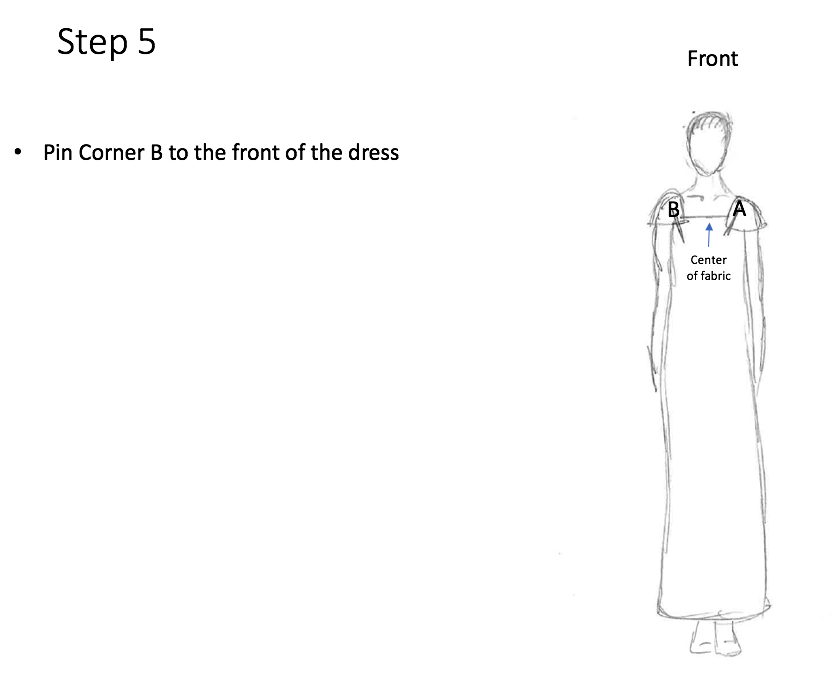

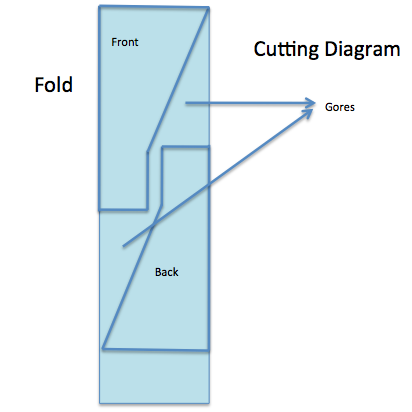

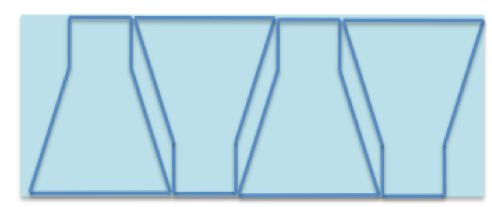

One of the options (Variant 4: Pustopolje type) is a very simple wrapped garment made from a rectangle of cloth. I have to take a moment here and note that it is expressly stated in the article that "none of the recreated outfits can be considered as 'the truth'". This is very key, they are all exceptionally hypothetical (and the methodology is laid out in the document itself, which I shall link further down). It does, however, work amazingly well and is quite beautiful in the linen that I tested! (There really is not enough to back this, even with this article, to give this garment enough to pass muster as an A&S project, but it certainly works for events like Pennsic, where I want to stay cool and comfy!)

https://www.academia.edu/10762573/Visions_of_Dress._Recreating_Bronze_Age_Clothing_from_the_Danube_Regionwww.academia.edu/10762573/Visions_of_Dress._Recreating_Bronze_Age_Clothing_from_the_Danube_Region

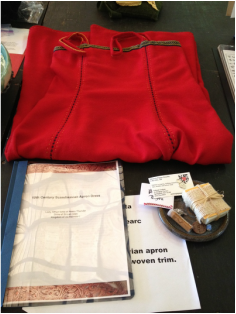

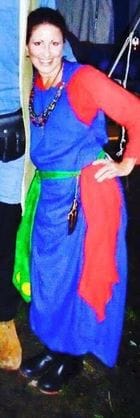

Below are some tests I did. This is 2 yards of 5.3oz linen, un cut and unhemmed. I tried it with and without a belt and both styles are secure. I can walk, climb stairs, get up and down off the ground and chase cats in it. For this test I simply used kilt pins. In reality I will hem the cloth and use my Crafty Celts Belt and Fibula set (which dates several hundred years after this, but I have it and it is stunning).

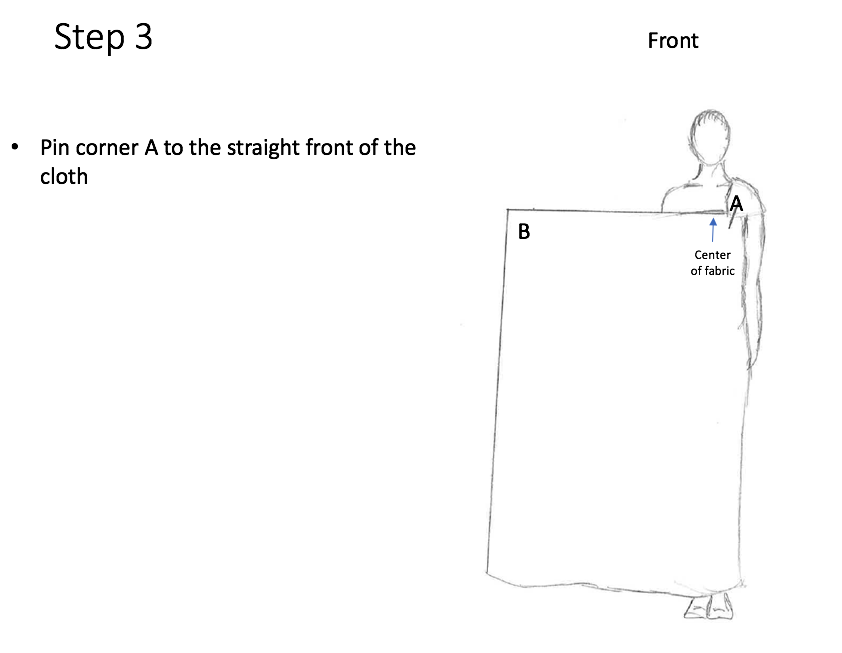

The only issue I have so far found at all was that the top-front (neckline) tends to ride a little high on me. That can be easily fixed with a small brooch or fibula in the front that would serve to gather just a bit of that fabric (pulling it a bit lower).

For sizing, I am typically an 8 or a woman's medium. I use two yards of cloth (before hemming) for this garment. My recommendation is to start with cloth that is double your bust size, PLUS extra. Wrap the garment and you can tell from there exactly how much you will need, and you can trim off the excess.

Last year I pushed the fibula through the dress fabric itself each time. This year I might add small hand sewn eyelets to pin through to help preserve the cloth.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed